COMPETITION ETC

D. RANDY RIGGS

THE ISDT QUALIFIERS -GETTING PERSONAL

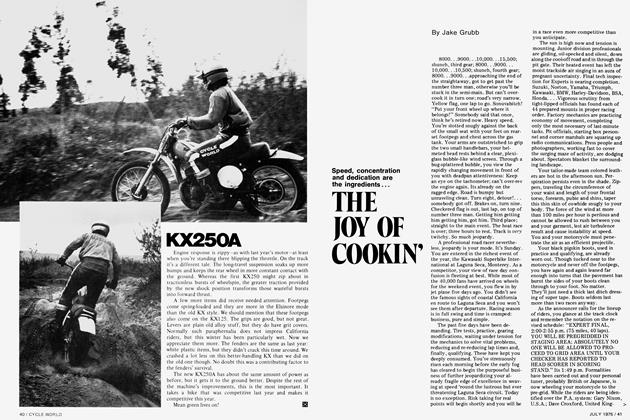

I suppose it was sometime last year that I began thinking about riding in an ISDT qualifier. Enduro riding had become somewhat of a passion with me because of the varied offerings of terrain and new trails. But the timekeeping aspect of the typical enduro was a big fat zero; I didn’t like to keep time when I started riding enduros, and I like it even less now. Quite obviously, I’m missing the whole point of an enduro, or at least ignoring it, and, though I didn’t mean that literally, it works out that way in practice. Points are my downfall in most enduros that I ride.

So what could I run that would be similar to an enduro without the hassle of keeping time? Answer: An ISDT qualifier.

Every year, more and more attention from U.S. motorcycle riders gets focused in the direction of the ISDT. It wasn’t long ago that a typical off-roader in the U.S. would greet you with a blank stare if you tried to spark a conversation concerning ISDT riding or riders. “On Any Sunday” introduced many in this country to the game; further interest came when the ISDT was held in the U.S. in 1973. And now, the qualifying rounds have turned into a whopping nine-event series all over the country.

Since our technical editor, Walt Fulton, had ridden in a couple of the qualifying rounds last year, I began quizzing him about what they were like. Before you knew it, he and I had talked ourselves into running about seven of the nine events to be held this year, not necessarily as a serious effort to make the U.S. Team, but more as an apprentice learning effort. Just what does it take to make the U.S. ISDT Team? That’s what we wanted to find out.

The first problem to solve was the matter of motorcycles. Walt and I pondered that one for quite a while. But since he had ridden a Bultaco 250 Matador all year without a DNF, and had the experience maintaining and preparing Buis, we thought Bultaco might be a good choice. . .particularly since they were about ready to release their new Frontera models, bikes designed around the axioms of a two-day qualifier. It’s also important that a motorcycle fit a rider; both Walt and myself seem to be molded around Bultaco traits and characteristics. Another point in Bultaco’s favor: Walt likes to ride the 250 class, I like to ride the Open class. The Frontera would be available in both sizes. We placed our orders.

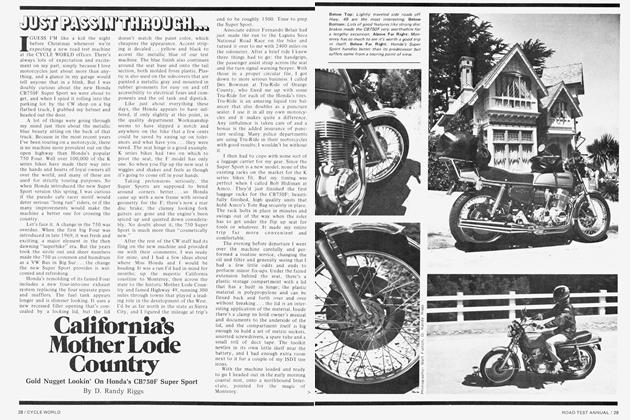

Quite naturally, though, things don’t always go as planned. As the days grew closer to our first two-day run at California City, the Fronteras hadn’t arrived. It was nip and tuck whether or not mine would make it in time; Walt’s 250 version was a couple of months away. Fulton’s only choice at that stage of the game was to prepare a 250 Pursang, the same machine we tested in our March issue. My 360 arrived just a few short days before the event.

With the help of Bultaco’s West Coast rep, Mike Hannon, I tore into the new Frontera to make sure everything was ready for California City. And if you’re going to be serious about a two-day, tearing into a machine means just that. You take it all apart, and you put it back together ever so carefully, checking clearances and every last nut and bolt on the motorcycle. Mike and I spent a hard 12 hours on the Frontera in anticipation of the 3000 miles of grueling competition it would be getting into in the following three or four months. But time had run out. Hoping for 200 miles of break-in before the first two-day, I only managed 45, and that’s not nearly enough time to get used to a machine, and for a machine to get used to itself.

I really can’t remember a time when I’ve been more nervous before an event. Guess it was the old thing about the unknown. A two-day is set up as a practice ground for the Six Day, so all the same rules apply. The machines are marked, impounded; riders carry few, but just enough tools to make on-thespot repairs. Flat tires can be crucial; learning to change them quickly is essential.

More emphasis this year is being placed on the special test scores, rather than route marks. But I found it hard to change my pace when entering a special test. After about five minutes of hard running, I would lapse back into my normal check-to-check rhythm. I had to keep telling myself this was a race against the clock and to gas it, which is hard when you’re running along out in the desert all by yourself. And, running with the number “lb,” I didn’t have much company.

Of course, falling in a special test is a no-no, and naturally I fell in one of the special tests on the first day. As it turned out later, the two minutes or so I lost getting going again cost me my gold medal. I missed the top 1 5 percent of my class by 20 seconds, after nearly 350 miles of riding. When I found that out I felt like I had swallowed a rock. But I learned how important it is to stay on two wheels in a special test. My mistake turned a gold medal to silver, which is a bummer lesson.

Again the motorcycle got a severe going over. Ft. Hood, Texas and Pell City, Alabama, were next on the twoday calendar. Ft. Hood was rumored to be dry and dusty, while Alabama was supposedly a mud bog. Of course, as it turned out, the opposite was true.

(Continued on page 104)

Continued from page 63

Ft. Hood was two days of the slipperiest mud Fve ever seen. The Frontera didn’t seem to mind it one bit, however, and kept amazing me with plunges through tank-deep water with nary a burp. My problem mainly concerned seeing, after coating goggles and spares with goo, and my glasses besides. And without glasses, this kid can’t pick out a trail from a tree. I backed off the throttle, lost the pace and momentum I had worked so hard to maintain, and finished on bronze.

If there is a key to running a twoday, it has to be resting squarely on frame of mind and mental attitude. I’m learning that more and more every time I ride, though more slowly than I had hoped. You have to learn to ignore the little things and plug onward at no reduction in speed. Keeping up that momentum is spurred by the right frame of mind. If you fall and tweak your knee, the pain has to be forgotten. Same goes for bent handlebars and the little things that can aggravate and throw off a rider of normal caliber. Ft. Hood pointed that out to me clearly, because I was able to think back to a few places on the run where trying harder would’ve earned me a silver rather than the bronze.

Walt and I were super pumped for Alabama. Helping in that respect were some of the most super people we’ve ever met going out of their way to see that we had places to stay and a spot to work on the Bultacos and shape them after Texas. Joe Patrick Jr. and his wife Clara made sure we had everything we needed, in spite of the fact that he was one of the Alabama two-day organizers and had more than his share of work to do. Honda Central in Birmingham, also a Bultaco dealer, made space in its busy shop and hunted down parts. The whole gang there is terrific, and if you ever need work done or a new motorcycle, they’ll treat you right.

Unfortunately, I only made it 122 miles into the first day at Pell City when a condenser went out, leaving me in the middle of the woods and damned unhappy. And Walt had problems, as well, but at least he got to day two. More flat tires than he would like to think about put him out of the running. After three events we had a gold, a silver, two bronzes and two DNFs. It’s tough business in a two-day and we’ve learned plenty. There’s lots of hard work just maintaining the motorcycles, harder work keeping in top physical shape, and the hardest thing of all is maintaining that all-important right frame of mind. We’ll be hangin’ in there though. That’s what it’s all about.