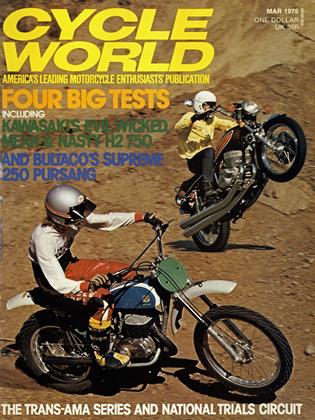

WORLD'S LARGEST HARE'N HOUND

Baaken and Mayes Share First-To-Finish Honors In The First-Annual Last Barstow To Vegas.

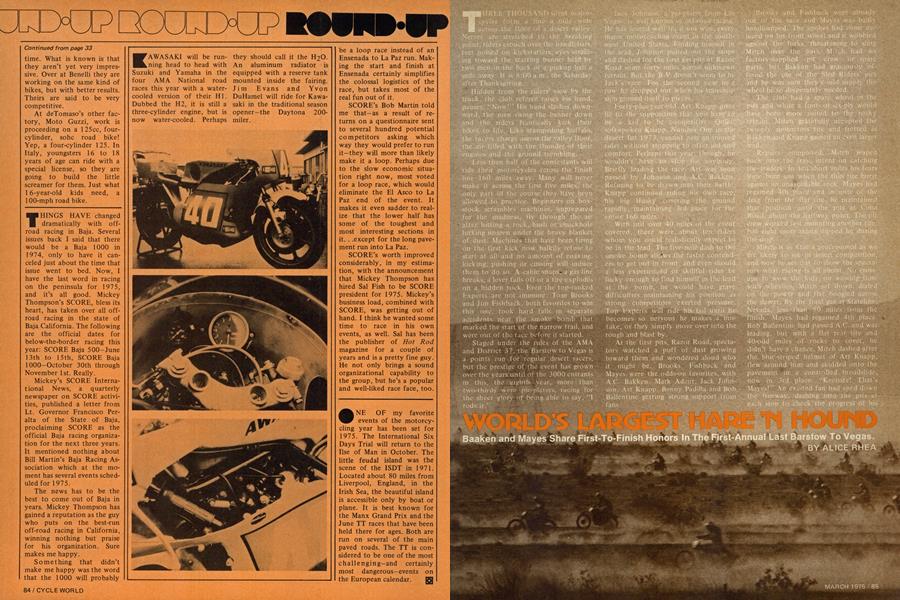

THREE THOUSAND silent motorcycle form a line mile wide across the floor of a desert valley. Nerves are stretched to the breaking point fiders crouch over the handlebars, feel poised on kickstarters, eyes straining toward the starting banner held by two men in the back of a pickup half a mile away It is 8:00 a.m., the Saturday after Thanksgiving.

Hidden' from the riders' view by the truck, the club referee raises his hand, pauses; “Now!" His hand slashes downward, the men swing the banner down anti the riders frantically kick their bikes to life. Like stampeding buffalo, the racers charge across the valley floor, the air filled with the thunder of their engines and the ground trembling, t Less than half of the contestants will ride their motorcycles across the finish line 160 miles away. Many will never make it across the first, five mites, the only part of the course they have been allowed to practice. Beginners on boxstock scrambles machines, unprepared for the madness, fly through the air after hitting a rock, bush or chuckhole lurking unseen under the heavy blanket of dust. Machines that have been firing on the first kick now balkily refuse to start at all and no amount of coaxing, kicking, pushing or cussing will induce them to do so. A cable snaps, a gas line breaks, a lever falls off or a fire explodes on a hidden rock. Even the top-ranked Experts are not immune: Tom Brooks and Jim Fishback, both favorites to win this one. took hard falls in separate accidents near the smoke bomb that marked the start of the narrow trail, and were out of the race before it started.

Staged under the rules of the AMA and District 37, the Barstow to Vegas is a points run for regular desert racers, but the prestige of the event has grown over the years until of the 3000 entrants in this, the eighth year, more than two-thirds were pie-platers, racing for the sheer glory of being able to say. “Í

Jack Johnson, a pie-plater from Làs Vegas, is well known in off-road racing. He has scored well in, if not won, every major motorcycling event in the southwest United States. Finding himself in the lead, Johnson pulled out the stops and dashed for the first gas pits at Razor Road some forty miles across unknown terrain. But the B-V doesn’t seem to be Jack's race. For the second year in a row he dropped out when his transmission ground itself to pieces.

For 1 y-phis-year-old Art Knapp gives lie to the supposition that you have to be a kid to be competitive. Quiet, soft-spoken Knapp. Number One in the desert for 1973, cannot pass an injured rider without stopping to offer aid and comfort. Perhaps this year, though, he * wouldn't have to stop for anybody. Briefly leading the race. Art was soon passed by Johnson and A.C. Bakken. Refusing to be drawn into their battle, Knapp continued riding his own race, his big Husky covering the ground rapidly, maintaining 3rd place for the entire 160 miles.

With just over 40 miles of the event covered, there were about ten riders whom you could realistically expect to be in the lead. The five-mile dash to the smoke bomb allows the faster contenders to get out in front, and even should a less experienced or skillful rider be lucky enough to find himself in the lead at the bomb, he would have grave difficulties maintaining his position as ; strong competitors exerted pressure. Top Fxperts will ride his tail until he becomes so nervous he makes a mistake, or they simply move over into the rough and blast by.

At the first pits, Razor Road, spectators watched a puff of dust growing toward them and wondered aloud who it might be. Brooks, Fishback and Mayes were the odds-on favorites, with A.C. Bakken. Mark Adent. Jack Johnson, Art Knapp. Benny Padilla and Bob Ballent ine getting strong support from fans. " .

„

Brooks and Fishback were already put of the race and Mayes was badly handicapped. The spokes had come unlaced on his front wheel and it wobbled against the forks, threatening to sling Mitch over the bars. Mitch had no factory-supplied pit crew or spare parts, but Bakken had graciously offered the use of the Sled Riders’ pits and he was sure they could supply the wheel he so desperately needed.

The club had a spare wheel in the pits and while a fouror six-ply would have been more suited to the rocky terrain. Mitch gratefully accepted the .two-ply motocross tire and fretted as Bakken.and Knapp gained an even larger lead.

. Repairs completed, Mitch leaped back into the fray, intent on catching the leaders In ten short miles his tears were born out when the thin tire burst against an unavoidable rock. Mayes had regained 4lh place and in spite of the drag from the flat tire, he maintained that position until the pits at Cima Road, about the halfway point. The pit crew worked fast mounting another tire, but eight more riders slipped by during the stop.

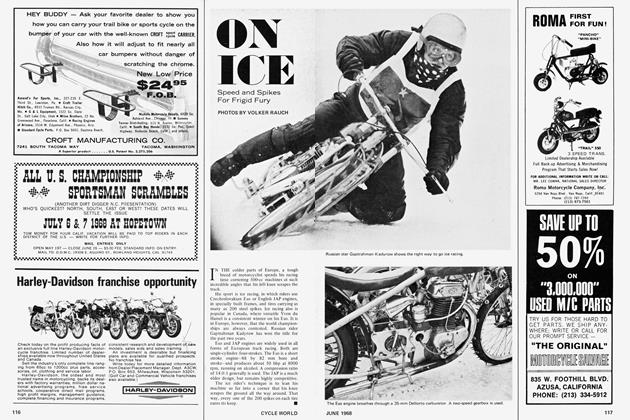

Mitch is as near a professional as we are likely to see in desert competition, and now he set out to show the spectators what racing is all about. No crossups to wow the kids, no wasting time with wheel íes, Mitch sat down, dialed on the:■-power ánd flat boogied across the desert. By the final gas at Stateline. Nevada, less than 50 miles from the finish. Mayes had regained 4th place. Bob Ballemine had passed A.C. and was leading, but with a flat rear tire and 40-odd miles of rocks to cover, he didn't have a chance. Mitch dashed after the blue-striped helmet of Art Knapp, flew around him and skidded onto the pavement, in a controlled broadstide, now in 3rd place. “Keeriste! That’s Mayes!” An excited fan had sped down the freeway, dashing into the pits at each stop to check the progress of his favorite and had last seen Mayes limping along with a flat. While expecting Mitch to stay in the race if he conld repair or replace the tíre, J Oth place was about the best that could be hoped for. But Mayes had regained his position and bettered it, making some of the best riders in the desert look like Novices in the process. Passing Sallentine, who was limping back to the pits on a naked rim. Mitch concentrated every ounce of energy and skill on catching A.C.

ALICE RHEA

A.C. Bakken is no slouch. He has already cinched the Number One heavyweight title for i975 and he had a good chance of winning this race. However, A.C. has a deep respect for rocks, knowing what they can do to both rider and machinery', and the last 40 miles of the race is paved with everything from pea-gravel to boulders. Less than 10 miles from the finish'A.C. heard Mitch dosing on him. coming within striking distance./

Nobody knows why the two riders did not enter a fierceduel for the glory of winning this prestigious event. Perhaps, inside, the only place it counts in the solitary world of desert racing. A.C.

and Mitch felt that they had done what they wanted. As they had done as a team in the Baja 1000 the previous year, the pair had shown that they were capable of outrunning and outlasting everybody else in the race. They grinned and waved at each other and. looking for all the world like two schoolboys playing hookey, crossed the finish line handlebar-to-handiebar. The sponsoring club is reluctant to allow the tie to stand, so Mitch said they should give the credit, and the points, to his friend A.C. A.C. insists that Mitch deserves credit for the win. At press time no decision has been made.

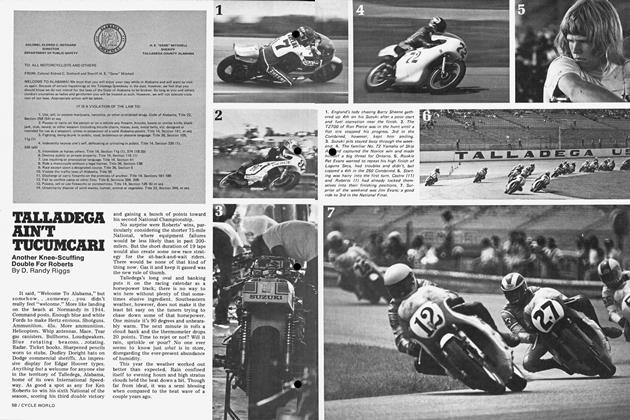

Still in 3rd place and with a bloody nose from a flying rock, but still smiling, Art Knapp rolled down the finish chute; the third 400cc Husqvarna to arrive.

And right behind him was a fourth

Husky. On it, Scott Harden, Las Vegas resident and last year’s first 250 at 3rd overall, and former winner of the Snore 250. An honor student and holder of his local association’s Number One in the 125 class for 1974, Scott switched to the 250cc class and has gained that top notch for 1975. Harden is a finisher and perhaps a little more experience will see him as the first non-member of District 37 to win the B-V one day.

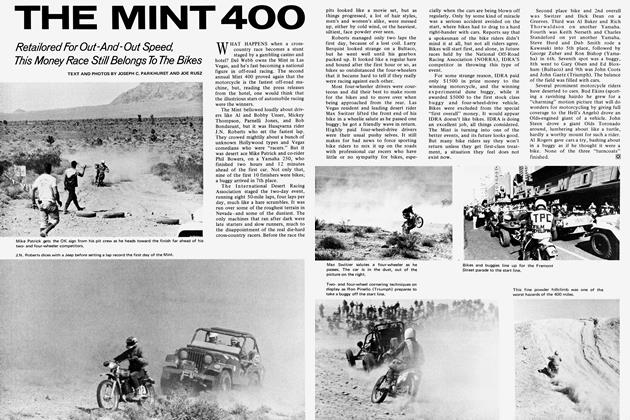

Three hours and 55 minutes had elapsed between the start and the nonchalant finish of A.C. Bakken and Mitch Mayes. By dark, 10 hours after the start, more than 1400 weary riders had staggered across the finish line. Exhausted racers and broken machinery lined the course awaiting rescue by fellow club members, friends and family, or the members of the U.S. Army who had volunteered to haul mutilated equipment out of the desert. Bikes were rendered inoperative by such small things as a lost bolt or broken cable, others would need new engines or gearboxes. However, a veteran desert racer wouldn’t let a minor problem keep him out of the race. Masters of the art of

jury-rigging, they can fix anything short of a blown engine with a little duct tape, bailing wire and ingenuity:

John “Smoke Bomb” Gates has been racing in the Mojave Desert since the dawn of time. . .well, maybe not quite that long. With his vast experience at breakdowns of all sorts over the years. Smoke Bomb wasn’t about to iet a little thing like a broken fuel line leave him sitting in the choking dust. Gates searched for a sharp rock, “You never can find one when you need it, but there is always one under me when 1 fall off,” he grumbled. Jerking the overflow tube out of his gas cap, Gates pounded it with a rock until it separated into two somewhat untidy halves. The improvised fuel line wasn’t a neat factory installation, but it worked and Smoke Bomb was able to get to Las Vegas shortly after the fiftieth rider was logged in. (Continued on page 110}

Continued from page 86

Hand-held throttle cables, bailing wire wrapped around parts come adrift when bolts shear, a screwdriver jammed into half a handlebar are included in the makeshift repairs. There are even those who won’t stop at tearing down two broken bikes to repair one and tow the other. No seasoned desert racer waits for rescue if he can possibly avoid it, for nothing so bores them as watching everybody else have all the fun.

The great classics are gone. No more Catalina Grand Prix, Big Bear or Elsinore. All that remains is the Barstow to Vegas and it, too, has been threatened for the past three years. Those who contend that anything other than a pair of hiking boots will destroy the land forever, have constantly brought pressure upon the powers that be to ban motorcycles from all unpaved surfaces. The men who would have to enforce such a ban, the BLM rangers, are a likeable group of people. Rangers sent to observe the race looked around to see where the sponsoring club, San Gabriel Valley M.C., was short-handed and pitched in without waiting to be asked. But if an injunction could be brought to stop the race, the rangers would have to follow orders. When the small club yelled for help, the AMA stepped in and retained a group of attorneys to ward off any suits and found an expert to study the environmental impact survey.

The Mojave Desert is more than a vast playground to the thousands of motorcyclists who visit it weekly; with its wildlife, plants, interesting rocks and geological formations, it offers a chance to commune with nature; to be alone and rediscover who you are and to share the camaraderie around a blazing campfire. And, for a while longer at least, we are holding on to it.

Was the 1974 Barstow to Vegas the last big cross-country motorcycle race we will ever witness? As you read this, San Gabriel Valley Motorcycle Club members are already preparing for the 1975 event.

And the racers, forgetting the dense dust, the bruises, the raw hands and broken bikes and the fact that less than half the starters saw the checkered flag, are saying, “Next year when I ride the Barstow to Vegas. ...” H

UNOFFICIAL RESULTS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontA New Column For Dirt Riders, A Note On the Cycle World Show, And A European-Style Gp In the U.S.?

March 1975 -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1975 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeedback

March 1975 -

Departments

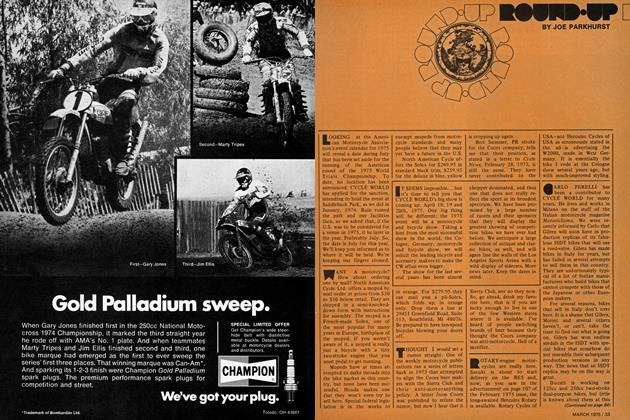

DepartmentsRound Up

March 1975 By Joe Parkhurst -

Features

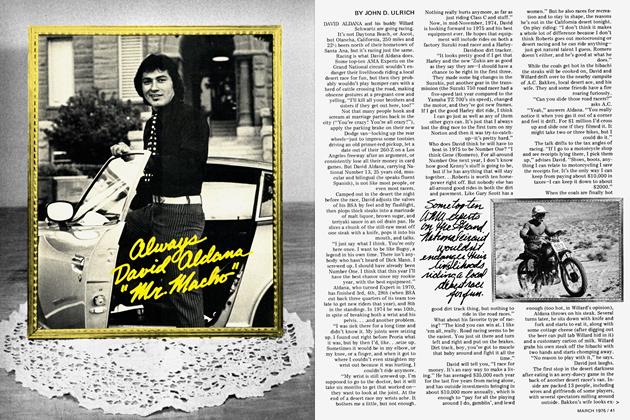

FeaturesAlways David Aldana "Mr. Macho"

March 1975 By John D. Ulrich -

Competition

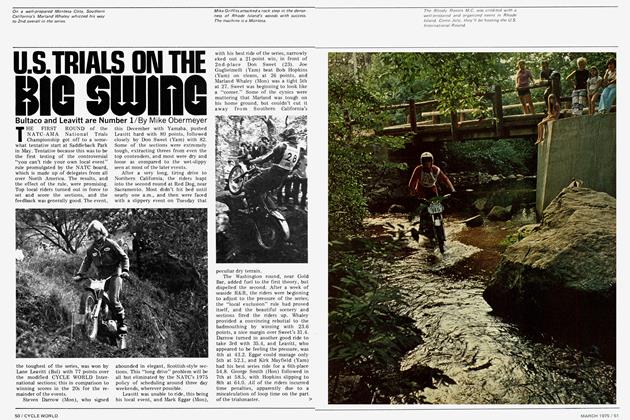

CompetitionU.S. Trials On the Big Swing

March 1975 By Mike Obermeyer