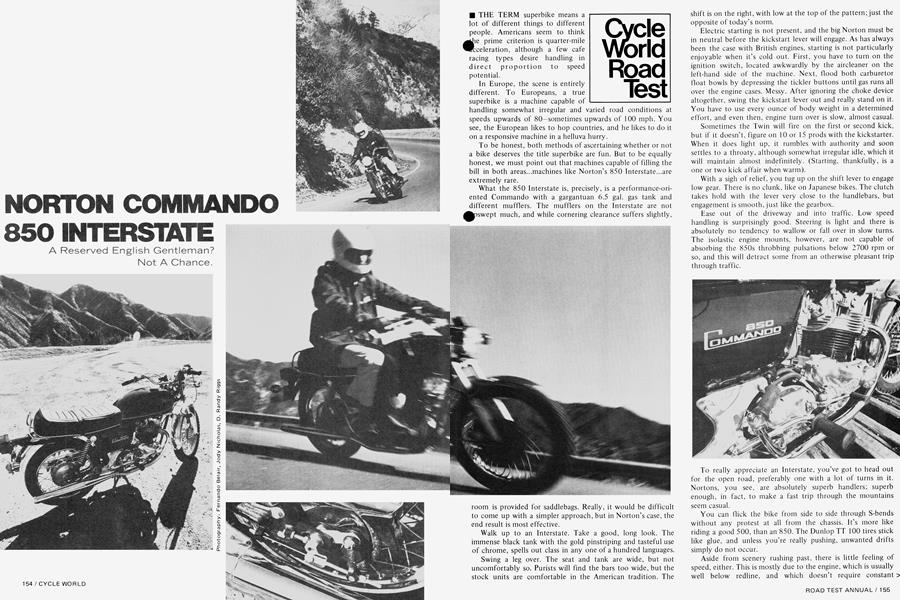

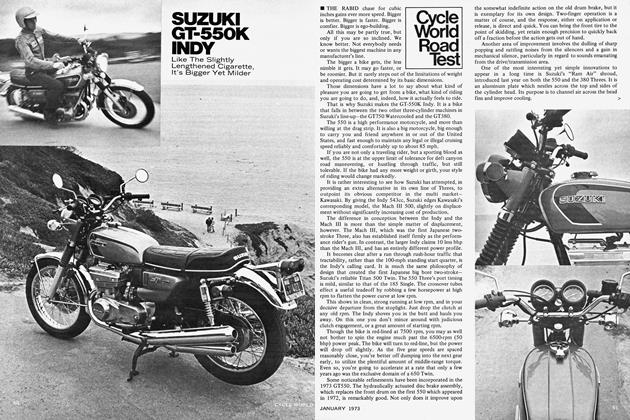

NORTON COMMANDO 850 INTERSTATE

A Reserved English Gentleman? Not A Chance.

Cycle World Road Test

THE TERM superbike means a lot of different things to different people. Americans seem to think the prime criterion is quarter-mile acceleration, although a few cafe racing types desire handling in direct proportion to speed potential.

In Europe, the scene is entirely different. To Europeans, a true superbike is a machine capable of handling somewhat irregular and varied road conditions at speeds upwards of 80-sometimes upwards of 100 mph. You see, the European likes to hop countries, and he likes to do it on a responsive machine in a helluva hurry.

To be honest, both methods of ascertaining whether or not a bike deserves the title superbike are fun. But to be equally honest, we must point out that machines capable of filling the bill in both areas...machines like Norton’s 850 Interstate...are extremely rare.

What the 850 Interstate is, precisely, is a performance-oriented Commando with a gargantuan 6.5 gal. gas tank and different mufflers. The mufflers on the Interstate are not swept much, and while cornering clearance suffers slightly, room is provided for saddlebags. Really, it would be difficult to come up with a simpler approach, but in Norton’s case, the end result is most effective.

Walk up to an Interstate. Take a good, long look. The immense black tank with the gold pinstriping and tasteful use of chrome, spells out class in any one of a hundred languages.

Swing a leg over. The seat and tank are wide, but not uncomfortably so. Purists will find the bars too wide, but the stock units are comfortable in the American tradition. The shift is on the right, with low at the top of the pattern; just the opposite of today’s norm.

Electric starting is not present, and the big Norton must be in neutral before the kickstart lever will engage. As has always been the case with British engines, starting is not particularly enjoyable when it’s cold out. First, you have to turn on the ignition switch, located awkwardly by the aircleaner on the left-hand side of the machine. Next, flood both carburetor float bowls by depressing the tickler buttons until gas runs all over the engine cases. Messy. After ignoring the choke device altogether, swing the kickstart lever out and really stand on it. You have to use every ounce of body weight in a determined effort, and even then, engine turn over is slow, almost casual.

Sometimes the Twin will fire on the first or second kick, but if it doesn’t, figure on 10 or 15 prods with the kickstarter. When it does light up, it rumbles with authority and soon settles to a throaty, although somewhat irregular idle, which it will maintain almost indefinitely. (Starting, thankfully, is a one or two kick affair when warm).

With a sigh of relief, you tug up on the shift lever to engage low gear. There is no clunk, like on Japanese bikes. The clutch takes hold with the lever very close to the handlebars, but engagement is smooth, just like the gearbox.

Ease out of the driveway and into traffic. Low speed handling is surprisingly good. Steering is light and there is absolutely no tendency to wallow or fall over in slow turns. The isolastic engine mounts, however, are not capable of absorbing the 850s throbbing pulsations below 2700 rpm or so, and this will detract some from an otherwise pleasant trip through traffic.

To really appreciate an Interstate, you’ve got to head out for the open road, preferably one with a lot ot turns in it. Nortons, you see, are absolutely superb handlers; superb enough, in fact, to make a fast trip through the mountains seem casual.

You can flick the bike from side to side through S-bends without any protest at all from the chassis. It’s more like riding a good 500, than an 850. The Dunlop TT 100 tires stick like glue, and unless you’re really pushing, unwanted drifts simply do not occur.

Aside from scenery rushing past, there is little leeling ol speed, either. This is mostly due to the engine, which is usually well below redline, and which doesn’t require constant shifting. The bike is almost vibrationless from mid-rpm on up. Just punch fourth and regulate your speed with the throttle. It’s as simple as that.

Brakes can handle the speed potential, too. There’s a disc up front, manufactured by Norton under license from Lockheed. The double-acting caliper presses the two 1.5-in. wide brake pucks against the 10.7-in. diameter disc for an effective swept area of 84 sq. in.

The disc has the stopping power all right, but unfortunately, the master cylinder is mounted to the handlebar as on the Japanese systems, with the front brake lever pressing directly on the master cylinder piston. This means that the brake begins working as soon as the lever is pulled, making it difficult for people with small hands to get a good grip on the lever. It would be very simple to put an adjusting screw in the lever to allow the rider to adjust the point of lever engagement with the master cylinder piston, but it has been overlooked for the second year in a row.

The rear brake is a conventional drum unit, which works well enough, but isn’t particularly impressive, especially after a fast ride through the hills. Naturally, most of the braking force is provided by the front brake, but the rear unit on the Interstate could stand some improvement.

Performance-wise, all Nortons, the Interstate included, must be considered innovative, because they’ve occupied the top rung on the ladder several times. But they haven’t accomplished this with futuristic design, especially where the engine is concerned!

Basic design for the Norton Twin is decades old; and changes, with the exception of displacement increases, have been subtle. Even after all the years, and the generally accepted superiority of horizontally-split crankcases, Norton still retains the vertically-split crankcase configuration. This makes the incorporation of a central main bearing difficult, although not impossible: AJS and Matchless vertical Twins used a central main bearing right up until they stopped being manufactured in the early 1960’s.

One of the main complaints that riders have about verically-split crankcases is that they are prone to leaking small amounts of oil. This is not the case on the Interstate, however, due to the large area of the mating surfaces and the obvious care which Norton uses in the machining of these areas.

In spite of the engine displacement increase from 745 to 828cc, which comes about by the use of 77mm pistons instead of smaller 73mm ones, the crankcase is identical to the 750, except for more metal being removed from the crankcase lips to accommodate the larger cylinder barrel. Strength to support the crankshaft in its roller main bearings is assured by generous cast-in webbing around the bearing bosses. The inevitable crankshaft “whip” such an engine design produces at ultra-high rpm, is also lessened by this webbing.

The connecting rods are still two-piece units featuring plain, thin-shell big-end bearings, with the pistons being supp<^^d by plain, brass bushings. Conventional three-ring flalRp pistons yield a compression ratio of 8.5 :1.

Also new on the Commando 850 is the cast-iron cylinder barrel. Besides being slightly larger physically, and having a 4mm larger bore, there are four holes running vertically on the outside edges to allow through-bolts to be employed. Earlier Nortons had the cylinder barrel attached to the crankcase by nine studs and nuts, and the cylinder head attached to the barrel by ten bolts and studs. Only in extreme situations did this arrangement give any trouble, but a cylinder would occasionally break loose from its cast-in lip if a piston s^^d. The four through-bolts eliminate this possibility.

Concentric 32mm carburetors feed the cylinders through> large intake ports, terminating at inlet valves with valve stem oil seals.

NORTON

COMMANDO 850

$2055

With the exception of the Kawasaki 650-RS, which is not being imported into the U.S. now, the Norton Commando is the only four-stroke vertical Twin being manufactured with a separate engine and transmission. In spite of the additional complication of having a two-piece primary chaincase, and additional castings for the transmission, the Norton system works very well. A rubber gasket effectively keeps oil in the primary chaincase and the transmission weeps only a tiny bit of oil from the kickstart and gearchange shafts.

A couple of interesting features are found inside the primary chaincase. First, a triple-row primary chain transmits the power from the crankshaft to the clutch with a minimum of power loss, and a huge eight-plate clutch unit features a diaphragm spring.

This spring was designed for Norton by the Laycock de Normanville firm, and has several advantages over the multispring arrangement found on most motorcycles. First, the spring maintains its tension equally at all points around its periphery, eliminating the chance of uneven clutch plate action. And, with the clutch actuating mechanism used by Norton, it is possible to arrive at nearly twice the spring pressure of a conventional clutch, without adding significantly to the clutch lever pressure required to disengage the unit.

Aside from the slight lowering (raising numerically) of the second gear ratio, the transmission remains unchanged from earlier Nortons. This was done to reduce the distance between the low and second gear ratios, making for smoother downshifts. Clutch action is excellent, and no slippage or dragging occurred even after a dozen runs down the drag strip.

Considering the number of old-fashioned designs found on the Commando, one of the most up-to-date and outstanding features of the motorcycle is the frame. Conventional in appearance, it is basically a single cradle design with a large, 2.5 in. diameter toptube, which runs rearward from the steering head to a point under the seat. There it merges into smaller diameter tubes, two of which extend rearward, forming a loop which the seat rides on, and to which the rear fender is attached. Two others curve downward and forward, eventually terminating at the steering head, finishing the loop.

The unusual part, however, is the method by which the engine, transmission and swinging arm are attached to the “main” frame. Resilient rubber mountings are employed at the front of the engine, at the top, rear end of the transmission and at the top of the engine.

Advantages of this mounting system are twofold: the rider is effectively insulated from the greatest part of the enrne’s vibration, adding to his comfort immensely. And. by moiUPng the swinging arm directly to the engine/transmission cradle, the rear wheel is not pulled out of line with the countershaft sprocket during hard acceleration, improving handling characteristics and reducing rear chain side wear by a marked degree.

The electrical chores are once again handled by an alternator/coil/battery system, which works just fine. Although a 12 volt system, the twin ignition coils are 6 volt units with a ballast resistor. Starting and high speed operation are aided by this setup which is often used in automotive ignition systems.

Also, there is an external “live” two-prong socket which may be used to connect a battery charger without removing the seat—or, you can use it to plug in your electrically heated riding vest or suit!

What the Interstate is, then, is an intriguing blend of carefully updated antiquated design (the engine), and innovative technology (the frame). What you get is a long distance hauler that’s a superbike for sure, but that’s not a bike for the masses. The masses will no longer tolerate the lack of electric starting, oil leaks, “Mickey Mouse” Lucas electrical control switches, and the like. But for those with a more td^^ant disposition, for the purist with sport in his blood, the Norton Interstate has been, is, and will continue to be, a favorite. 03

View Full Issue

View Full Issue