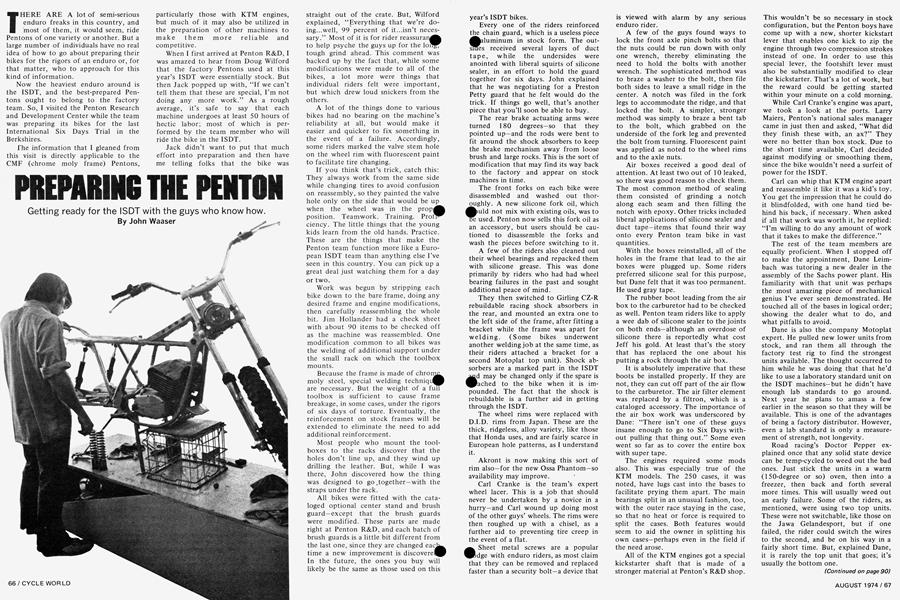

PREPARING THE PENTON

Getting ready for the ISDT with the guys who know how.

John Waaser

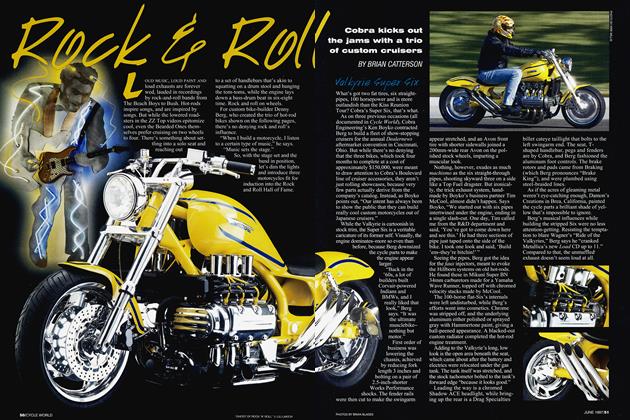

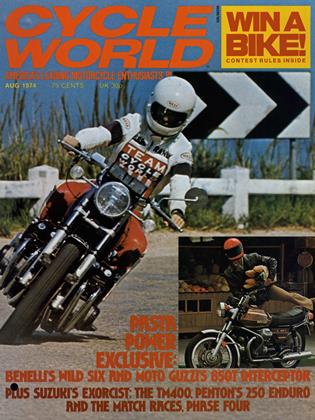

THERE ARE A lot of semi-serious enduro freaks in this country, and most of them, it would seem, ride Pentons of one variety or another. But a large number of individuals have no real idea of how to go about preparing their bikes for the rigors of an enduro or, for that matter, who to approach for this kind of information.

Now the heaviest enduro around is the ISDT, and the best-prepared Pentons ought to belong to the factory team. So, I visited the Penton Research and Development Center while the team was preparing its bikes for the last International Six Days Trial in the Berkshires.

The information that I gleaned from this visit is directly applicable to the CMF (chrome moly frame) Pentons, particularly those with KTM engines, but much of it may also be utilized in the preparation of other machines to make them more reliable and competitive.

When I first arrived at Penton R&D, I was amazed to hear from Doug Wilford that the factory Pentons used at this year’s ISDT were essentially stock. But then Jack popped up with, “If we can’t tell them that these are special, I’m not doing any more work.” As a rough average, it’s safe to say that each machine undergoes at least 50 hours of hectic labor; most of which is performed by the team member who will ride the bike in the ISDT.

Jack didn’t want to put that much effort into preparation and then have me telling folks that the bike was straight out of the crate. But, Wilford explained, “Everything that we’re doing...well, 99 percent of it...isn’t necessary.” Most of it is for rider réassurai to help psyche the guys up for the loi tough grind ahead. This comment was backed up by the fact that, while some modifications were made to all of the bikes, a lot more were things that individual riders felt were important, but which drew loud snickers from the others.

A lot of the things done to various bikes had no bearing on the machine’s reliability at all, but would make it easier and quicker to fix something in the event of a failure. Accordingly, some riders marked the valve stem hole on the wheel rim with fluorescent paint to facilitate tire changing.

If you think that’s trick, catch this: They always work from the same side while changing tires to avoid confusion on reassembly, so they painted the valve hole only on the side that would be up when the wheel was in the prop position. Teamwork. Training. Prof ciency. The little things that the young kids learn from the old hands. Practice. These are the things that make the Penton team function more like a European ISDT team than anything else I’ve seen in this country. You can pick up a great deal just watching them for a day or two.

Work was begun by stripping each bike down to the bare frame, doing any desired frame and engine modifications, then carefully reassembling the whole bit. Jim Hollander had a check sheet with about 90 items to be checked off as the machine was reassembled. One modification common to all bikes was the welding of additional support under the small rack on which the toolbox mounts.

Because the frame is made of chron^L moly steel, special welding techniqd^B are necessary. But the weight of a full toolbox is sufficient to cause frame breakage, in some cases, under the rigors of six days of torture. Eventually, the reinforcement on stock frames will be extended to eliminate the need to add additional reinforcement.

Most people who mount the toolboxes to the racks discover that the holes don’t line up, and they wind up drilling the leather. But, while I was there, John discovered how the thing was designed to go .together—with the straps under the rack.

All bikes were fitted with the cataloged optional center stand and brush guard—except that the brush guards were modified. These parts are made right at Penton R&D, and each batch of brush guards is a little bit different from the last one, since they are changed eacl^ time a new improvement is discoveret^P In the future, the ones you buy will likely be the same as those used on this year’s ISDT bikes.

Every one of the riders reinforced the chain guard, which is a useless piece ^^aluminum in stock form. The outsraes received several layers of duct tape, while the undersides were anointed with liberal squirts of silicone sealer, in an effort to hold the guard together for six days. John explained that he was negotiating for a Preston Petty guard that he felt would do the trick. If things go well, that’s another piece that you’ll soon be able to buy.

The rear brake actuating arms were turned 180 degrees—so that they pointed up—and the rods were bent to fit around the shock absorbers to keep the brake mechanism away from loose brush and large rocks. This is the sort of modification that may find its way back to the factory and appear on stock machines in time.

The front forks on each bike were disassembled and washed out thoroughly. A new silicone fork oil, which ^fc>uld not mix with existing oils, was to be used. Penton now sells this fork oil as an accessory, but users should be cautioned to disassemble the forks and wash the pieces before switching to it.

A few of the riders also cleaned out their wheel bearings and repacked them with silicone grease. This was done primarily by riders who had had wheel bearing failures in the past and sought additional peace of mind.

They then switched to Girling CZ-R rebuildable racing shock absorbers in the rear, and mounted an extra one to the left side of the frame, after fitting a bracket while the frame was apart for welding. (Some bikes underwent another welding job at the same time, as their riders attached a bracket for a second Motoplat top unit). Shock absorbers are a marked part in the ISDT

«d Cached may be to changed the bike only when if the it spare is imis pounded. The fact that the shock is rebuildable is a further aid in getting through the ISDT.

The wheel rims were replaced with D.I.D. rims from Japan. These are the thick, ridgeless, alloy variety, like those that Honda uses, and are fairly scarce in European hole patterns, as I understand it.

Akront is now making this sort of rim also—for the new Ossa Phantom—so availability may improve.

Carl Cranke is the team’s expert wheel lacer. This is a job that should never be undertaken by a novice in a hurry—and Carl wound up doing most of the other guys’ wheels. The rims were then roughed up with a chisel, as a further aid to preventing tire creep in the event of a flat.

Sheet metal screws are a popular dge with enduro riders, as most claim that they can be removed and replaced faster than a security bolt—a device that is viewed with alarm by any serious enduro rider.

A few of the guys found ways to lock the front axle pinch bolts so that the nuts could be run down with only one wrench, thereby eliminating the need to hold the bolts with another wrench. The sophisticated method was to braze a washer to the bolt, then file both sides to leave a small ridge in the center. A notch was filed in the fork legs to accommodate the ridge, and that locked the bolt. A simpler, stronger method was simply to braze a bent tab to the bolt, which grabbed on the underside of the fork leg and prevented the bolt from turning. Fluorescent paint was applied as noted to the wheel rims and to the axle nuts.

Air boxes received a good deal of attention. At least two out of 10 leaked, so there was good reason to check them. The most common method of sealing them consisted of grinding a notch along each seam and then filling the notch with epoxy. Other tricks included liberal applications of silicone sealer and duct tape—items that found their way onto every Penton team bike in vast quantities.

With the boxes reinstalled, all of the holes in the frame that lead to the air boxes were plugged up. Some riders preferred silicone seal for this purpose, but Dane felt that it was too permanent. He used gray tape.

The rubber boot leading from the air box to the carburetor had to be checked as well. Penton team riders like to apply a wee dab of silicone sealer to the joints on both ends—although an overdose of silicone there is reportedly what cost Jeff his gold. At least that’s the story that has replaced the one about his putting a rock through the air box.

It is absolutely imperative that these boots be installed properly. If they are not, they can cut off part of the air flow to the carburetor. The air filter element was replaced by a filtron, which is a cataloged accessory. The importance of the air box work was underscored by Dane: “There isn’t one of these guys insane enough to go to Six Days without pulling that thing out.” Some even went so far as to cover the entire box with super tape.

The engines required some mods also. This was especially true of the KTM models. The 250 cases, it was noted, have lugs cast into the bases to facilitate prying them apart. The main bearings split in an unusual fashion, too, with the outer race staying in the case, so that no heat or force is required to split the cases. Both features would seem to aid the owner in splitting his own cases—perhaps even in the field if the need arose.

All of the KTM engines got a special kickstarter shaft that is made of a stronger material at Penton’s R&D shop. This wouldn’t be so necessary in stock configuration, but the Penton boys have come up with a new, shorter kickstart lever that enables one kick to zip the engine through two compression strokes instead of one. In order to use this special lever, the footshift lever must also be substantially modified to clear the kickstarter. That’s a lot of work, but the reward could be getting started within your minute on a cold morning.

While Carl Cranke’s engine was apart, we took a look at the ports. Larry Maiers, Penton’s national sales manager came in just then and asked, “What did they finish these with, an ax?” They were no better than box stock. Due to the short time available, Carl decided against modifying or smoothing them, since the bike wouldn’t need a surfeit of power for the ISDT.

Carl can whip that KTM engine apart and reassemble it like it was a kid’s toy. You get the impression that he could do it blindfolded, with one hand tied behind his back, if necessary. When asked if all that work was worth it, he replied: “I’m willing to do any amount of work that it takes to make the difference.”

The rest of the team members are equally proficient. When I stopped off to make the appointment, Dane Leimbach was tutoring a new dealer in the assembly of the Sachs power plant. His familiarity with that unit was perhaps the most amazing piece of mechanical genius I’ve ever seen demonstrated. He touched all of the bases in logical order; showing the dealer what to do, and what pitfalls to avoid.

Dane is also the company Motoplat expert. He pulled new lower units from stock, and ran them all through the factory test rig to find the strongest units available. The thought occurred to him while he was doing that that he’d like to use a laboratory standard unit on the ISDT machines—but he didn’t have enough lab standards to go around. Next year he plans to amass a few earlier in the season so that they will be available. This is one of the advantages of being a factory distributor. However, even a lab standard is only a measurement of strength, not longevity.

Road racing’s Doctor Pepper explained once that any solid state device can be temp-cycled to weed out the bad ones. Just stick the units in a warm (150-degree or so) oven, then into a freezer, then back and forth several more times. This will usually weed out an early failure. Some of the riders, as mentioned, were using two top units. These were not switchable, like those on the Jawa Gelandesport, but if one failed, the rider could switch the wires to the second, and be on his way in a fairly short time. But, explained Dane, it is rarely the top unit that goes; it’s usually the bottom one.

(Continued on page 90)

Continued from page 67

Then there were a lot of things that individual riders did to their machines that others did not feel were necessary. One of the brightest was the use of a Honda SL70 headlight sealed beam unit wedged into the front number plate with foam rubber, with the rim bolted to the plate to retain it, and all electrical connections covered with the everpresent silicone.

Tom and Jeff both did that number. It is said to be the most reliable headlight ever run through an enduro. When you can lose points for not having a working headlight after six days, that’s important.

Doug Wilford and Tom Penton shared the honors for the single weirdest contraption: a “suck tube” on the

carburetor float bowl. The tube originates at the carburetor overflow, and passes through a large automotive fuel filter, which acts as a reservoir. A healthy toke on the tube clears that flooded condition that is prevalent when a bike has tipped over. Doug gave a demonstration and Carl said, “I can feel that in my shorts.” Actually, you get the impression that Doug and Tom are gasoline freaks—most guys would rather kick all day than risk a mouthful of petrol.

Another interesting accessory on Doug’s bike was a box formed of galvanized steel fastened to the front down tubes and just the right size to carry a spare chain. The box was really neat. It protected the chain and afforded easy access to the spare chain, but the weight was kind of high. If only they could have mounted the spare chain just above the bash plate, below the engine.

In fact, it was Wilford and Tom Penton who shared most of the really innovative ideas...like a folding shift lever that looked like the top of a kickstart lever and that folded back if it contacted brush or rocks. Thus, it would be virtually impossible to bend the shift lever, and no time would be lost straightening that component.

For spring tension, the boys used a strip from an old inner tube, bound with a plastic tie strip to the brush guard. Varying the length of the tie strip altered the spring pressure on the shift lever. The lever itself was a bit larger than most—it could afford to stick out more—and so was more comfortable to shift with boots on. There was very little likelihood of the boot slipping off of the shift lever.

This would be more difficult to accomplish on the KTM-engined machines, as that shift lever has some more serious bends in it. The Sachs engine shift lever is straight. Wilford’s bike also sported a 175 exhaust system and front forks from the larger series machines.

(Continued on page 92)

Continued from page 90

Even the multi-wrenches, those handy little gadgets that every enduro rider designs for himself, in order to do as many jobs as possible with one tool, differed from rider to rider. I thought that Jack’s was the neatest. It looked like something that you’d expect to go out and buy. (Maybe Joe Bolger will read this and put one on the market...). Some of the others were crudely assembled sections cut off of other wrenches. Jack holds his in place by first slipping it over the rear shock absorber nut, then using the ever-present ring cut from an old inner tube to tie it to the rear frame section. Everybody had his own favoriJÄ location and method of tying the to^P to the frame.

Dane Leimbach was the slowest worker of the group—probably due at least in part to the fact that he handled all of the Motoplat work for the entire group, and did a lot of other helping with different things. Carl Cranke was the only one to finish his bike while I was there, and the completion of the first Six Day bike was cause for a small celebration.

Carl fired up the bike and took it across the street for a slow session of familiarization. Jack wanted to get it on, and Carl finally relented, handing the machine over to the younger Penton with an admonition not to wear the edges off the blocks on the tires. Jack did wear down the tires a bit, but all was forgiven.

Another factor that will determiH the success of a rider in an enduro is support. Penton would be supporting the entire Penton trophy team, the Italian trophy team, who were also mounted on Penton/KTMs, plus a few individuals from club teams. Ted Penton was in charge of that facet of the operation. He said, “We can’t help everybody, but we won’t turn anybody down.” That’s a big order. It means tires, lubricants, fuel, refreshment and personnel to care for upwards of 20 riders for six days—not to mention the illicit support available at any ISDT to those who need it and know how to get it. A whole article could be written on that subject alone.

As I suggested earlier, it may be more important to set up the rider than the machine for a major enduro or trial, but there is a great disparity of opinion as ta how to go about doing that. Da^ Eames set a cut-off date beyond which he would not ride any enduros or motocross, for fear of injuring himself and not being able to compete in the ISDT. So what happened? On the last enduro he was going to ride, he broke a leg. Luckily it was not a bad fracture and he healed in time to ride the ISDT.

(Continued on page 94)

Continued from page 92

But the Penton family takes the opposite approach. They feel that you can get hurt anytime, anywhere. The weekend before they were scheduled to depart for the Berkshires, some of them rode the Jack Pine, while some of them went up to the Corduroy in Canada. John feels that you have to stay keen to be competitive, so you should ride right up until the last day, always striving to win.

The week before the Jack Pine, the Penton team scored a first-five sweep at the Hungry Creek 100, for instance.

Joe Barker thought that the best way to set himself up for the ISDT would be to go home and practice changing tires. “You can do that here,” somebody suggested. “No, everybody laughs,” he replied. Jack didn’t much like the idea of riding his heart out at the Corduroy. He wanted to rest. But he didn’t have much to worry about. His father wanted to ride the old man’s class at the Jack Pine—an enduro that’s going to have to be named after him someday—and didn’t have a bike to ride. “I’m kinda safe,” noted Jack, “ ‘cause Dad’s riding my bike at Jack Pine.”

If you think these guys prepared their Six Days bikes in a hurry, you should have seen them getting ready for the Corduroy. They were leaving at 6 a.m., so at 11 o’clock the night before, Tom started working on his bike—th^ same one he’d ridden at every din^B enduro all year. It was a mess; but these guys know exactly what has to be checked, and what parts can be left alone. This familiarity with the machine, is absolutely vital in ISDT competition; another indication that the bike can be prepared quickly, but that the rider takes years to prepare.

Just how stock were these ISDT bikes? Wilford said they would sell their ISDT bikes after the event to anybody who wanted to buy one. Dane Leimbach said he’d bring enough money to buy his, but all were in agreement that they wouldn’t really want a bike that had been through an ISDT. Getting it right again would be more work than starting from scratch with a new machine.

When Carl Cranke first finished his bike, Jack Penton turned to him an^^ said, “All that work you did, and it ju^P looks like you put a new front fender on it.” And that’s the truth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

August 1974 -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

August 1974 -

Departments

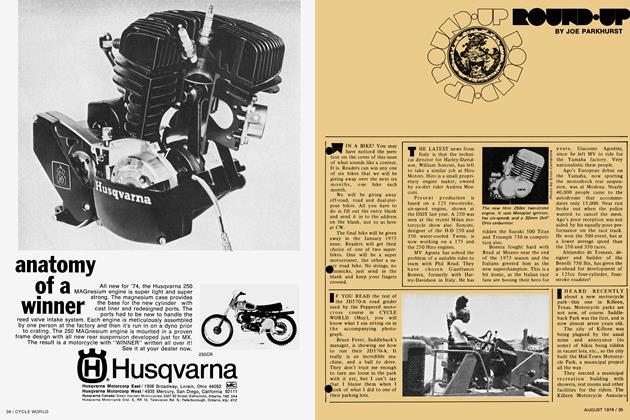

DepartmentsRound·up

August 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

Features

FeaturesNineteen Seventy Four Cycle World Show

August 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

Competition

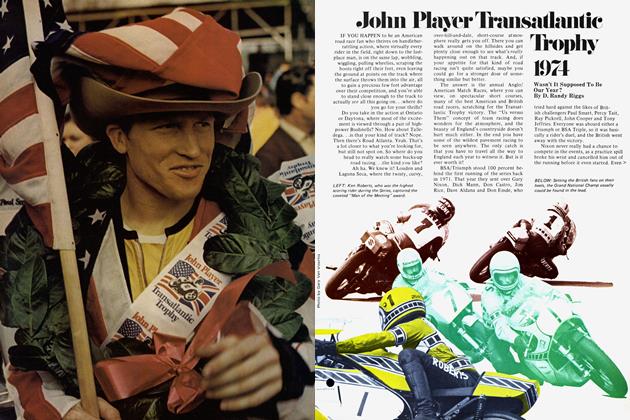

CompetitionJohn Player Transatlantic Trophy 1974

August 1974 By D. Randy Riggs