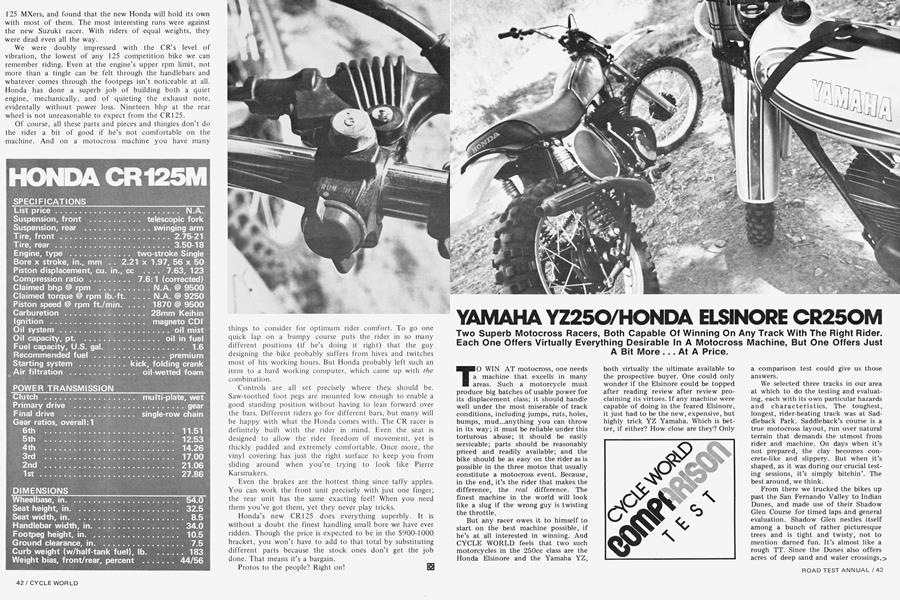

YAMAHA YZ250/HONDA ELSINORE CR250M

CYCLE WORLD COMPARISON TEST

Two Superb Motocross Racers, Both Capable Of Winning On Any Track With The Right Rider. Each One Offers Virtually Everything Desirable In A Motocross Machine, But One Offers Just A Bit More ... At A Price.

TO WIN AT motocross, one needs a machine that excells in many areas. Such a motorcycle must produce big batches of usable power for its displacement class; it should handle well under the most miserable of track conditions, including jumps, ruts, holes, bumps, mud...anything you can throw in its way; it must be reliable under this torturous abuse; it should be easily servicable; parts should be reasonably priced and readily available; and the bike should be as easy on the rider as is possible in the three motos that usually constitute a motocross event. Because, in the end, it’s the rider that makes the difference, the real difference. The finest machine in the world will look like a slug if the wrong guy is twisting the throttle.

But any racer owes it to himself to start on the best machine possible, if he’s at all interested in winning. And CYCLE WORLD feels that two such motorcycles in the 250cc class are the Honda Elsinore and the Yamaha YZ, both virtually the ultimate available to the prospective buyer. One could only wonder if the Elsinore could be topped after reading review after review proclaiming its virtues. If any machine were capable of doing in the feared Elsinore, it just had to be the new, expensive, but highly trick YZ Yamaha. Which is better, if either? How close are they? Only

a comparison test could give us those answers.

We selected three tracks in our area at which to do the testing and evaluating, each with its own particular hazards and characteristics. The toughest, longest, rider-beating track was at Saddleback Park. Saddleback’s course is a true motocross layout, run over natural terrain that demands the utmost from rider and machine. On days when it’s not prepared, the clay becomes concrete-like and slippery. But when it’s shaped, as it was during our crucial testing sessions, it’s simply bitchin’. The best around, we think.

From there we trucked the bikes up past the San Fernando Valley to Indian Dunes, and made use of their Shadow Glen Course for timed laps and general evaluation. Shadow Glen nestles itself among a bunch of rather picturesque trees and is tight and twisty, not to mention darned fun. It’s almost like a rough TT. Since the Dunes also offers acres of deep sand and water crossings, it was here that we conducted two other important phases of our comparison—a 200-yard timed run across the meanest set of whoop-de-doos you’ll ever want to see, and a non-forgiving wet test through a couple of shallow sections of stream. These watered sections closely duplicated wet hazards one might find at a typical motocross meet.

The last course we churned dirt on was Escape Country’s demanding little track. It wasn’t prepared as well as it might have been for our mid-week test session, but its condition was about the same as it would have been during a latter moto on race day.

Three totally different courses, each with its own set of nooks and crannies waiting to bite the unsuspecting rider and machine. It would be a hard, grueling week of testing, but it would also give us the proof we needed to come up with a winner for our first Motocross Comparison Test.

Bob Atkinson, D. Randy Riggs, and Jody Nicholas would handle the riding chores each day, and Joe Parkhurst, our fearless publisher, joined in at Escape Country to add his comments and impressions.

Helping with the photography and timing were Roger Morrison and Randy Papke from the CYCLE WORLD Art Department. Their presence made things a whole lot easier for the rest of the staff, so we let them out on one of the courses for a few wide-eyed laps on both machines.

The Elsinore arrived a week earlier than the Yamaha, and our initial test session was spent with Honda’s George Etheridge at Indian Dunes. George is highly involved with the CR250’s progress and development, and likes to see magazine testers go away knowing all there is to know about his babies. And at the end of the test session, we can always count on oP George having a well-stocked cooler full of various liquid refreshments, so that’s an added bonus.

Etheridge had three 250s with him that day; one was stock and expressly for our test; one had a soon-to-beoffered optional “kit” with different carb, cylinder and piston, and one was experimental with turned down fork tubes and shocks, magnesium hubs, and a beautifully formed aluminum swinging arm. We were allowed to sample the “kit” machine, but not the much altered version, which reportedly weighed 8 lb. less than a standard Elsinore, and it was all “unsprung” weight.

The Dunes track had been watered that morning shortly before we began riding; it was in pretty good shape, churned up and loamy in places, with only a few bothersome ruts.

Cold engine starts on the Honda require the use of the choke, so the rider must first depress the enriching lever on the 34mm Keihin carburetor before the friendly “prod” is given. The fuel petcock has only off and on positions, and is well recessed and out of the rider’s way. In our experience we have snagged fuel taps with riding leathers, dinged our leg and messed up the petcock well enough to put the bike out of commission! We’re glad to see Honda has placed theirs in a safe location. The chromed kick start lever is also well out of the rider’s way, yet swings out handily, ready for quick use. Rather than use a rubber goodie on the end of the lever where the rider places his foot, Honda simply casts in a knurled surface to allow good traction for the rider’s boot on the “kick-through.” The rubber

items never seem to stay on, anyway.

Once the off/run/off kill switch is checked for proper position, the engine

should fire after one or two kicks with no throttle used. The choke must remain in use for two or three minutes; then the engine readily accepts more throttle.

Easy warm-up laps proved instantly that the CR250 is well dialed in. The machine is supremely comfortable in a stand up or sit down riding position. Jody’s 5 ft., 7 in. bod fell right into place on the bike; he was quite happy with the placement of pegs, bars etc.

Bob and Randy are virtually identical in height and weight, and their 6-ft. frames were accommodated nicely on the CR as well. Randy would have liked another inch of rise in the bars, but everything else fit him fine.

One is immediately impressed with the Honda’s suspension. Offering over 7 in. of travel in the forks and 4 in. of stroke in the rear shocks, bumps you would expect to jolt you never do. The Elsinore literally “glides” over the irregularities to a degree that’s hard to comprehend. The only time we could complain was when diving hard into a corner rippled with a series of holes; then the CR did some rear end hopping, the kind that bothers you. In our test of the CR125 (CYCLE WORLD, Sept. ’73) the same kind of hopping occurred in the same type of situation, but it did not seem to affect the machine’s stability or the rider’s control. With the CR250, that is not the case. Especially impressive are hard landings just after heart seizing jumps. The rider can hear the ground thud and watch bystanders’ awed expressions, but the Honda doesn’t even blink. With a wheelbase of 57.1 in., 5.7 in. of trail, and a fork rake of 31 degrees, stability on front wheel landings and at high speeds over rough ground is amazing. Here the rider is in complete control.

But that long, stretched-out geometry makes itself felt in the tight corners. The front wheel wants to “push” and slide out before the rear, making it almost impossible to dive under someone in a first or second gear turn; the rider is in a much better position to pick off his foes around the outside. Some adjustment is available to help the situation, however. The rake can be decreased and the trail can be shortened by lowering the fork tubes in the aluminum triple-clamps up to an inch. Marks are provided at the top of the tubes so the rider can set the units accurately and return to a previous setting easily.

Experiments at American Honda indicate that future production machines may have a shorter wheelbase with both the trail and rake reduced somewhat, so we aren’t the only ones unhappy with the Elsinore’s steering.

Power generated by the 248cc Single is nearly astonishing, and yet there is nothing really radical about the unit. Instead, Honda’s first production twostroke shows a great deal of innovative design and a large amount of accepted two-stroke engineering. The cylinder ports are a prime example of such technology. Looking down the intake port we find one side extending higher into the cylinder. This effectively increases the port area without making the holes wider and increasing the chance of a piston ring getting caught in the port. The ring locating pins in the piston are situated in the center of the split inlet port, each extending down as far as the top of the staggered ports.

Four huge transfer ports are directed so that efficient cylinder filling takes place with a minimum of unburned gases going out the exhaust pipe. And, just as with the CR125, exhaust ports have “eyebrows” at their tops to increase port area near the top of the piston’s stroke. The combination of the “trick” porting and a correctly designed (and quiet) exhaust system, make the CR250 a very efficient and somewhat miserly engine as far as fuel consumption goes. We discovered later that even after running an identical number of laps as the YZ Yamaha, it never took as much fuel to refill the tank.

The engine’s lower end is fairly conventional. Ball bearings support the pressed together crankshaft in the crankcase halves, there is a roller bearing at the connecting rod’s big end, and needle bearings carry the piston, which is etched to retain the lubricating oil longer. Straight-cut gears drive the clutch assembly, which is quite light and exceptionally positive in action. And, like we would expect, primary kick starting is featured.

It was evident from the first lap on the Honda that we were putting to use one of the finest gearboxes in existance. The five-speed unit is a true gem...absolutely faultless. Gearbox ratios are super-close, which keeps the rider busy, but relaxed. He simply knows the Honda is going to shift up or down at the instant he feels it necessary. Clutch or no clutch, this gearbox works. Careful design and superb manufacturing techniques have made the CR250M transmission an example for others to follow.

Forged malleable aluminum alloy brake and shift levers resist damage, yet can be bent easily back into shape when necessary. In fact, the shift lever is so strong that some owners have actually bent the shifter shaft and caused damage inside the transmission when they fell on the lever. Drilling a series of holes in the lever arm will weaken it sufficiently to allow it to bend more readily without damage to the gearbox, but not enough to cause the lever to break off during normal operation.

Ignition is by flywheel magneto which provides a nice, hot spark for easy starting and an even stronger one as revs build up. The magneto and related wires are well sealed from the elements, and had the Honda passing our water test with no problem.

Great detailing is evident in the crankcases and outer covers of the CR engine. The covers are cast from a magnesium alloy to help reduce weight, and total dry engine weight with carburetor in place is 64 lb., lighter than several other units of the same displacement.

Shock absorbing rubber mounts support the alloy-bodied Keihin carburetor from both ends. It is a close copy of a Mikuni, and has an excellent system of air filtration. The element itself seemed to filter out virtually all the junk the naked eye can see; it uses an outer layer of a fibrous material, backed up underneath by the more common polyurethane foam. Its filtering agent is any good grade of SAE 10W30 oil. The airbox cavity is formed by the seat, side panels, and inner fender section, but water can and does get in through a few openings. The filter can be removed by anyone with a screwdriver in about 35 seconds. Returning the clean element doesn’t take much longer.

The CR250’s frame is a clean design that is extremely rigid. Manufactured from 4130 chrome moly tubing, the single loop cradle unit is heavily gusseted in the steering head area and in other highly stressed points. The chrome moly swinging arm is supported on bakelite fiber bearings, an item that has plagued several owners. The bearings elongate after 3 or 4 months of fairly regular racing, and all of a sudden the rider notices that his Elsinore is doing things it never did before! We know of one accessory company that is already in the process of making stronger and longer lasting replacement bearings, but the stock ones work fine if you don’t mind replacing them often.

We couldn’t help but admire the Elsinore’s beauty; it looks lean and hungry and ready to go. The fuel tank weighs 5 lb. with the screw-on cap in place and secures to the frame with three 10mm bolts. Capacity is 1.8-gal. of fuel and oil mixed at the ratio of 32:1. The tank is formed of dent-resistant aluminum, and just wide enough to allow the rider some grip with his knees. To get the tank off, the seat has to go first, but that only adds a few seconds of time. The seat base is thin aluminum, and the vinyl covering over the ample padding provides a good non-slip surface. The seat unit weighs just 4 lb., 2 oz.

Daido aluminum rims are considered the hot tip these days and the CR250 has them as standard equipment. Hubs are aluminum and spokes are larger in diameter at their point of intersection with the hub, to prevent breakage. The front brake has ample stopping power and superb feel, but the rear unit wasn’t like we expected. It chatters considerably, and though it’s not as bad as some, it could stand some improvement.

At the end of that first day of riding, we were quite doubtful that any other machine in the Honda’s class could top it. It had only a few bad manners, but it was a big step ahead of anything else we had sampled. Truly an excellent and superior first effort, with a reasonable price tag of $1145 to boot!

When the new Yamaha YZ arrived, we couldn’t have been more anxious to get out to the tracks. It was looking as though the comparison would turn out extremely close, though the Yamaha was starting out with a points deficit before the throttle was even turned, due to an extremely high initial purchase price. A motocross rider has to be pretty serious before he is willing to shell out over $1800 for a 250cc racer.

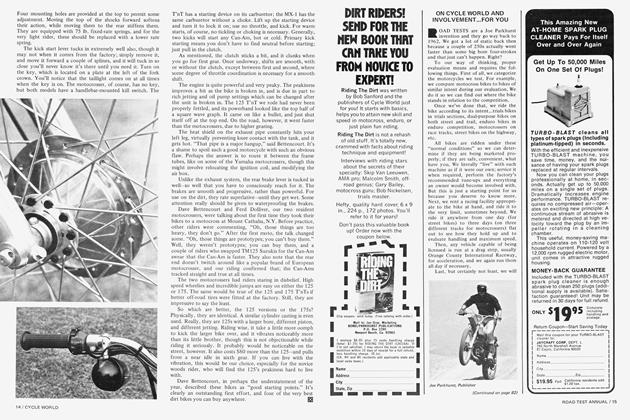

Our initial cost category was set up thusly: We felt that $1000 would be an ideal price for a motocross machine in this displacement bracket, and every $100 above that figure would mean a loss of one point from the 10 possible at the $1000 figure. The Honda CR, at a suggested $1145 retail, received a solid 9 points, while the YZ Yamaha, at an astronomical $1836, was only awarded 2. At this point, the Honda led, 9 to 2.

One can’t help but wonder what you get in a 250 MXer for $1800, but it becomes obvious when the YZ is given a thorough going over. We have long heard the cry of, “Those factory guys get all the neat stuff...wish we could buy one.” Well, now you can, but you’re gonna have to pay dearly. The new YZ is virtually identical to last year’s “factory” bikes, with all the trick parts and goodies.

Styling differs considerably from the bright yellow standard motocross models in Yamaha’s lineup. The tank is formed from aluminum and is finished in silver with red and black striping. Removing the 3 lb., 8 oz. unit takes little time, as it is held in place on rubber mounts with quick release straps. Very sanitary and proto.

The YZ sits high, too high in fact. Even our taller staffers were reaching for the ground with their toes, since the seat height is a tall 34.5 in. Most of this height is created by an overabundance of seat padding, so it can be remedied. Another item we would change is the handlebars, much too wide for our preferences. Aside from these, the YZ feels just right. A high mounted exhaust system tucks in the frame, the engine unit is narrow and foot controls and peg placement are ideal.

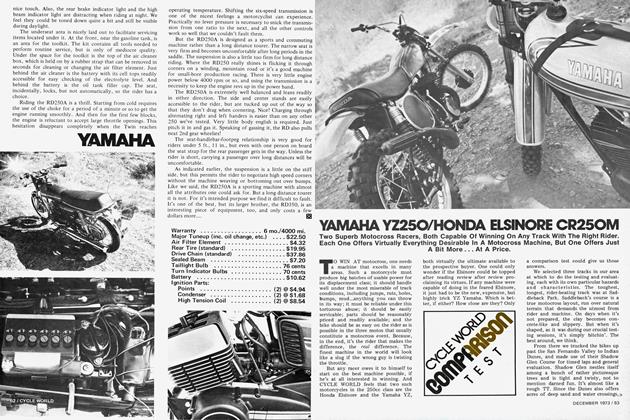

After throwing a leg over the Elsinore, and then climbing on the YZ, one can instantly tell that both machines are as different as night and day. But the Honda just plain feels better. It sits low and gives the impression of ground hugging capabilities. The YZ feels top heavy and short; like it’s waiting to highside the first rider that comes along. Taking a lap however, swings feelings in the opposite direction.

A rider is immediately aware that he is not riding any ordinary Yamaha; in fact, close your eyes and it seems like you’re straddling a super-fast, lightweight Husky! Did we say fast? That is an understatement. The YZ, even with an inadequate 4.00-18 rear tire, gobbles up ground in great leaping chunks, so you’d better be ready.

Starting is as simple as the Elsinore; a one or two-kick operation with no particular hassles. Adequate warm-up is necessary before the engine runs smoothly; by then the rider is moving around the course at a respectable clip. The suspension ignores the small surface irregularities, unlike the Honda, but works just super over the really bad stuff. Our machine had the new softer springs installed on the rear shocks; early models came through with spring rates that were far too stiff, and the result was a “pogo” effect.

That’s all been cleared up now. Over severe ripples and spine bending whoop-de-doos the units work superbly. Weighing 4 lb., 4 oz. each, the dampers are slightly heavier than the CR’s 3 lb., 12 oz. units, due to the addition of a large oil reservoir that is part of the front portion of the lower shock body. Though the YZ components do resemble the shocks found on Yamaha’s enduro models, a dab of red paint on their rear portion identifies them as having much more sophisticated damping characteristics. >

Once we had a few easy laps under our leathers it was time to get serious. A handful of the quick-turn throttle produces the feeling of being shot out of a giant rubberband. It’s a very controllable, yet instantaneous type of acceleration. If the rider wants, he can easily carry his front wheel over the rough stuff just enough to miss...not in a giant, out of control, wheelie. With the Honda, one has to work a bit to get the front end up; the YZ does it as the rider’s command, even at higher speeds.

The YZ doesn’t mind taking shots at corners off the berm, but it willingly takes an inside line as well. In almost every type of turn the YZ could get under the Elsinore and explode off the corner into the lead, and it makes it look easy. But the rider has to be ready to shift constantly due to the quick revving nature of the engine. And the shift lever travel is so short that it has you wondering if the next gear has been selected.

Probably the nicest thing about the YZ is its extremely light feel; though it weighs less than the CR250 by only about 5 lb., it gives the impression that there’s a greater difference. A more enjoyable riding motocrosser is hard to find. Yet, novices would probably not come close to using the YZ’s potential. It takes an expert to really use the Yamaha to its fullest, but that goes for the Elsinore as well.

Little has been borrowed from standard motocross models in Yamaha’s line, and what has, is tricked up. Fork legs look as though they’ve been turned down in a lathe and other pieces show much handwork in evidence.

Mechanically speaking, the most radical departure from current two-stroke design in the YZ250 is the reed-valve induction system. The reed-valve intake method isn’t new to Yamaha; they’ve been using it for a couple of years on many of their other models. Most producers of two-stroke motorcycles rely on the tried and true piston port or, in a few instances, the rotary valve induction system.

It’s interesting to note just how much of the handwork we were speaking of has gone into the YZ’s engine.

CATEGORY SIX-WATER TEST (POSSIBLE 10 POINTS)

Six passes were made with each bike through a double set of water crossings, both approximately 20 feet long with a dry 25-ft. section separating them. Five points were given for relatively dry air filter elements and an additional five points awarded if the engine remained running throughout this segment. Both machines had wet air filters when the test was completed, so neither got five points here. The Yamaha, however, quit on the third trip through the wet stuff, so it lost its chance of scoring in this bracket. Its spark plug cap was the culprit. TOTAL Honda .... 5 Yamaha . . 0

The right hand outer cover is a prime example and although it’s not magnesium, but aluminum, it is lighter and smaller than a standard outer cover. The rough finish indicates that it’s a sand casting rather than a die casting, and the bulge is barely large enough to accommodate the clutch inside.

Here is another example of Yamaha’s attention. The clutch wheel is steel, but liberally drilled to lessen rotating weight. Plain clutch plates are steel and the lined plates are aluminum alloy. Every attempt has been made to prune off excess ounces in the power and transmission departments. The constant-mesh transmission features gears that are incredibly narrow and light in weight.

(Continued on page 105)

HONDA CR250M

$1145

YAMAHA YZ250

$1836

DYNAMOMETER TEST: HORSEPOWER AND TORQUE

Continued from page 51

Ball bearings support the crankshaft which is of an unusual design: the flywheels have been hollowed out and a steel band goes around the outer rim to reduce the crankcase volume. Some riders have complained that the hollow flywheels make the YZ too responsive; and solid, heavier flywheels will be available to satisfy them, though we felt the YZ' was just right as is. Roller bearings support the connecting rod while needle bearings support the piston pin. The piston is a one-ring design with a curious cut-out on the rear edge to permit proper operation of the reed valve.

Although the cylinder is in actuality a 6-port design, the inlet port is stepped down in size near the top. When the piston passes this step it changes the port size and makes it possible for Yamaha to call it a 7-port cylinder. The ports are huge, but conventionally shaped. The cylinder liner is chrome plated for long wear and the single piston ring is cast iron for quick seating and good sealing.

Ignition is provided by an inner rotor capacitive discharge system which also reduces the apparent flywheel effect. These ignition systems provide a built-in advance curve, advancing the ignition timing as the revs build up. This is especially important when it is necessary to lug the machine down in a gear, because it makes the engine produce slightly more power at these lower engine revolutions.

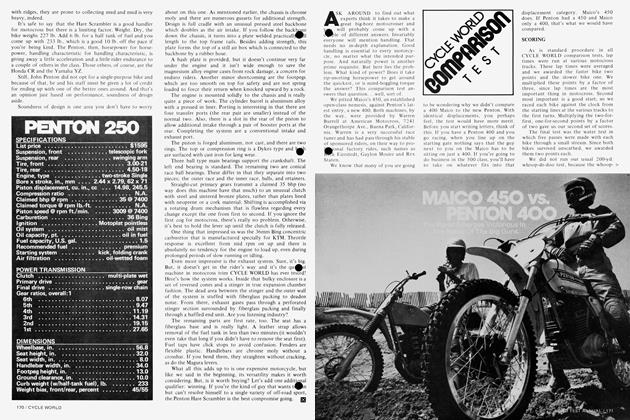

Naturally, the main reason for the Yamaha’s excellent handling qualities is the frame. It is patterned directly after last year’s works bikes and features a lower engine position than the standard Yamaha MXers. The frame is a double cradle design with the twin downtubes running from a heavily gusseted steering head down under the engine and curves back up behind it, eventually terminating in the sides of the single toptube. Additional tubes run from the rear of the engine cradles up to the rear suspension top mounting points. A horizontal tube connects to each rear engine cradle tube and runs rearward to form a mounting position for the seat and rear fender.

Fork rake is 30 deg. and trail measurement is 5 in. These dimensions, coupled with a 56-in. wheelbase, provide good stability over rough terrain and yet allow the YZ to steer fairly quickly on dry, hard surfaces without “pushing” the front end excessively. Oddly enough, the frame is still constructed from mild steel but is of better quality than the standard Yamaha MX, with thinner walled tubing.

Also interesting about the YZ frame is the bearing arrangement for the swinging arm. Two double bearings are used, each with a horizontal and a vertical thrust surface. They should last long time, but when it comes time for replacement, expect to pay a premium price!

(Continued on page 120)

Continued from page 105

Braking action from the tiny front brake and the good sized rear brake is beyond reproach. Even in rough terrain, smooth, positive stops for corners could be made. That doesn’t sound like a Yamaha motocrosser—does it? Both wheel hubs are aluminum, but very light in weight. In addition, the rear wheel hub is drilled for lightness without weakening the structure.

But the YZ is a real racing machine and demands plenty of upkeep. Even running the recommended 15:1 fuel/oil ratio on Castrol R 30, the top end should be removed after every meet and the piston inspected. Nothing shook loose during our test, but accessible nuts and bolts should be tightened periodically and everything checked for integrity. Yamaha’s understatement of the year was in the form of a sticker on the rear fender, “Warning, this vehicle is made for competition only.” Thanks, we needed that.

It is extremely difficult to properly evaluate and compare motorcycles designed expressly for motocross racing. In the case of the Honda Elsinore and the Yamaha YZ, it is double the trouble, since both machines are superb for their intended use. So close are the bikes that it is mind boggling, yet there is still one machine out of the two that we at CYCLE WORLD feel has the advantage; the object being winning at motocross.

We selected six categories that we felt were imperative and important to the prospective buyer. The first two involved cost considerations; what the bikes sell for new, and what it will cost to keep them running. We selected random dealers around the country for the figures you see on these pages; they may differ slightly from the ones quoted you by your dealer, but in any case they will be close. The Honda went away from these two divisions smelling like a rose, with a 9-point lead. But that doesn’t mean that the CR250 is inexpensive; a look at the price tables will tell you different.

It’s just that the YZ Yamaha is so expensive, but the high cost of both machines is bolstered by the fact that there is little or nothing the owner will have to add. We know many a motocrosser that costs the same or more, and the owner has to add plenty to the figure to make them right.

Then comes the dirt performance aspects. How do you judge such subjective data? Easy. You assemble together several experts whose years of competition and riding experience allow them to make concrete judgments, and you time them. You use different tracks, different conditions, and you swap the riders from bike to bike.

Our testing was conclusive. The YZ Yamaha was undefeated in the race to the first turn, and it was, on the average, a faster machine on timed laps, with four different riders. Times were close, but then, so are the bikes. If one took some of the time differences and multiplied them out over the number of laps in a 30 minute moto, the differences would be much greater. But then, that’s in theory. Anything can happen in a race.

Our sandwash test solidified the Yamaha’s power advantage, but to bang across whoop-de-doos requires handling and good suspension as well. The final test was the water drench.

Score? Out of a possible 53 points in 6 categories, the YZ Yamaha was the winner, 24 to 23. It was that close. Now you, the reader, the possible prospective buyer...you must decide if this small advantage is worth an extra $691. If you’re really a serious racer, it just might be worth it. If not, for just a bit more money than the YZ, you can buy the Elsinore and a 125 class racer, besides. Which would be the most fun is, of course, up to you.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue