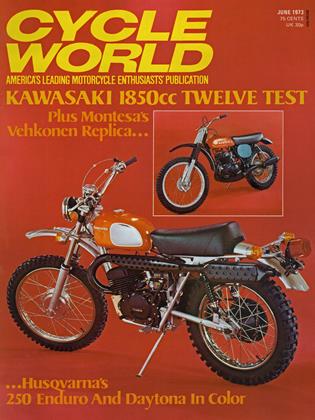

TWELVE-CYLINDER KAWASAKI TEST

Cycle World Road Test

NO, THIS isn’t a test of the most outlandish superbike ever invented...a twelve-cylinder behemoth with more power and bulk than sanity allows. Rather, it is an evaluation of Kawasaki’s total offering of performance oriented two-stroke Threes.

The offering consists of four bikes in four displacements. An image maker is the 750cc H2; a machine with enough power to command respect from any rider. Next comes the redesigned 500cc HI; a handler of late with acceleration 650 vertical Twin owners can only dream of. Then, there’s the nimble 350 which excels when following a crooked line. And last, a new 250 is available for those who think in terms of speed but can’t afford the bill.

Displacement throughout the range varies greatly, but all the Threes do have one thing in common—style.

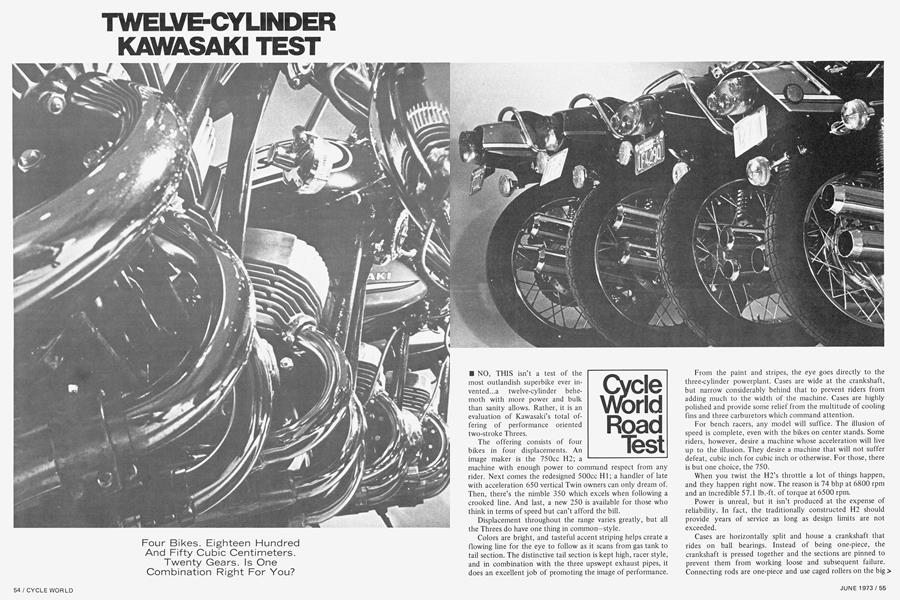

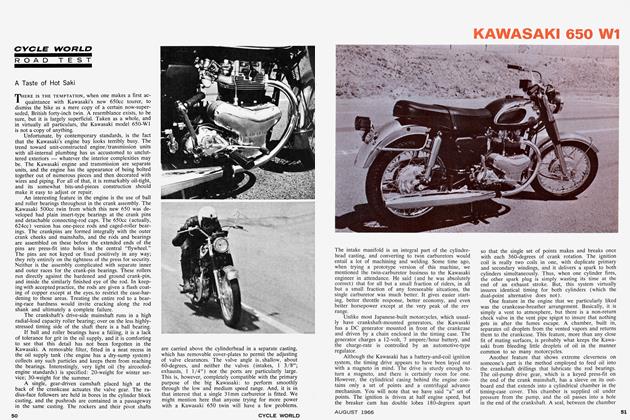

Colors are bright, and tasteful accent striping helps create a flowing line for the eye to follow as it scans from gas tank to tail section. The distinctive tail section is kept high, racer style, and in combination with the three upswept exhaust pipes, it does an excellent job of promoting the image of performance. From the paint and stripes, the eye goes directly to the three-cylinder powerplant. Cases are wide at the crankshaft, but narrow considerably behind that to prevent riders from adding much to the width of the machine. Cases are highly polished and provide some relief from the multitude of cooling fins and three carburetors which command attention.

For bench racers, any model will suffice. The illusion of speed is complete, even with the bikes on center stands. Some riders, however, desire a machine whose acceleration will live up to the illusion. They desire a machine that will not suffer defeat, cubic inch for cubic inch or otherwise. For those, there is but one choice, the 750.

When you twist the H2’s throttle a lot of things happen, and they happen right now. The reason is 74 bhp at 6800 rpm and an incredible 57.1 lb.-ft. of torque at 6500 rpm.

Power is unreal, but it isn’t produced at the expense of reliability. In fact, the traditionally constructed H2 should provide years of service as long as design limits are not exceeded.

Cases are horizontally split and house a crankshaft that rides on ball bearings. Instead of being one-piece, the crankshaft is pressed together and the sections are pinned to prevent them from working loose and subsequent failure. Connecting rods are one-piece and use caged rollers on the big > end. Needle bearings are featured at the small end of the rod.

Pistons are unusual in that they have three rings. Most two-strokes use only two compression rings and some racing units only use one. The pistons ride in conventional, individual barrels constructed of aluminum alloy with a cast in iron liner.

Unlike Suzuki, which opted for a one-piece head on its Threes, Kawasaki has retained a separate head for each cylinder. There is a lot of justification for this approach. For one thing, it allows easier repair of a troublesome cylinder. It minimizes replacement cost in the event the cylinder head is damaged in a crash, or as a result of piston failure. And, it is much easier for backyard mechanics to retorque small heads with fewer bolts in the pattern.

To minimize horsepower loss, primary drive is by straight cut gears. Usually straight cut gears are noisy, but under most load conditions, those in the H2 are not. Unfortunately, whatever is gained here is lost in piston slap and other irritating mechanical noise in the 3000 rpm and under bracket.

The clutch is a wet, multi-disc unit, as is common practice, and although lever pressure is not particularly light, it certainly isn’t objectionable. Slippage is not a problem as long as the proper oil is kept in the gearbox and the unit releases completely, making rapid shifts a snap.

The transmission is a five-speed with neutral at the bottom of the pattern. Although this arrangement makes neutral easy to engage in town, it does take some getting used to, especially on roads with really tight turns. Gearing on the H2 is pretty tall, so sometimes it is easy to convince yourself that there is another cog below first. Try it at the wrong time, in the wrong turn, and you will certainly have your hands full avoiding a crash.

On the positive side, lever travel is short and gear engagement is pr&cise. It is an ideal transmission for drag racing; one area of racing where a single missed shift means certain defeat. Gear ratios are also well-chosen, although first cog is a bit high for around town use.

The 750 Three is housed in a full, double cradle frame which leaves us with mixed thoughts. Wheelbase is 55.5 in., which is a good balance between stability and ease of handling at slower speeds. Both the basic frame ioop and swinging arm seem sturdy and flex free and there is adequate ground clearance for really hard cornering.

So, far, it sounds really good, but the chassis requires two steering dampers to control wobbles, even though the forks are raked out to a fair degree. The main damper is hydraulic and links up the lower triple-clamp with the right down tube,just under the gas tank. A knob at the rear allows adjustment of the damping rate.

For minor adjustments while traveling down the road, there is an additional friction damper mounted in the steering head. Loosening this lessens the steering chore in traffic. Tightening it down slightly increases stability at turnpike speeds.

Now, back to the wobble. As long as you are traveling a relatively straight line, even at near maximum speed, stability remains excellent in all but one situation. If you encounter rain grooves at approximately 70 mph, the H2 will begin wobbling its head whereas none of the other Threes tested do under identical conditions. Also, the H2 has a tendency to wobble slightly when braking in a turn. The harder the braking, the greater the speed, the more severe the wobble.

While the tendency to wobble is by no means a oixer s dream, it must be stressed that this phenomenon was never severe enough to create a hazard and we are not suggesting that the H2 is not a good bike for motoring at relatively substantial speeds. It is.

Excellent brakes and firm suspension, although not firm enough to cause rider discomfort, make the 750 an excellent>

bike for day trips. The seat is comfortable, vibration is minimal (nonexistent in the rear footpegs) and controls, while not as attractive as those found on the other Threes, are simple and easy to use.

Needless to say, cruising down the freeway is effortless, passing cars is completed before you realize it, and 40 miles per gallon is possible if extreme care is exercised.

The bike is suitable for short trips, but make no mistake about it, the machine is a lot happier when running hard. It is particularly appropriate for drag racing, especially in amateur ET bracket competition. Grab a handful of throttle, hang on, and some 12 sec. or so later it will be over!

A better choice for turns, but a bike with still enough speed to scare you is the 500cc HI. Early Mach III owners will no doubt ponder over our choosing the 500 as a better bike for cornering, but now His are vastly superior than the original in this respect.

Completely redesigning the frame, which, incidentally, bears little resemblance to the 750 unit, was not necessary. Instead, Kawasaki engineers stretched out the wheelbase to 55.1 in. by substituting a longer swinging arm and they increased fork rake by 1 degree. The result is more stability and slightly slower steering.

You can take the HI and lay it over hard in a turn. Steering is very precise and nothing scrapes or even comes close to dragging. Although the chassis seems to function best through a series of fast, relatively smooth sweepers, the HI can be thrown from side to side on rougher mountain roads with a good deal of confidence.

As on the 750, suspension is firm enough to keep the bike from wallowing and brakes are absolutely first rate. Both the front disc and the rear drum have good feel and their engagement is progressive. The front unit, incidentally, is identical to the one fitted on the 750.

Like the chassis, the 500 engine only resembles the 750 in concept. The engines do not share the same bore and stroke dimensions and few, if any, components are interchangeable. Both engines do, however, have pressed together, pinned crankshafts, ball bearings in the lower end, three ring pistons, and individual barrels and heads.

Again, there are three carburetors, although they are slightly smaller at 28mm than the 30mm Mikunis fitted to the 750. Again, capacitive discharge ignition eliminates bothersome points and provides more consistent ignition timing. And, again, autolube precludes the mixing of gas and oil.

Design-wise, the 500 and 750 are very close, but they really aren’t the same to ride. The 500 is decidedly more peaky in terms of powerband and really doesn’t come alive until 6000 rpm. Also, the unit has a tendency to load up in the 4-5000 rpm range if under load. This is especially true on cool days, which prevent the engine from reaching normal operating temperature.

We asked Kawasaki if this was correctable and they felt it wasn’t. Dropping the needles leans out the mixture too much on days when the Three is running hot and clean. As is, the resulting poor throttle response isn’t something you can’t live with. You just have to compensate with a few more rpm.

Fortunately, the 500 is blessed with an excellent transmission, although neutral is again at the bottom of the pattern. Ratios are well-chosen so it isn’t really difficult to keep the wailing 500 within its 1500 rpm powerband.

Shifting at a modest 7000 rpm, where 42.3 lb .-ft. of torque is on tap, is sufficient even when pulling steep grades two-up.

If you’re really in a hurry, 7500 rpm and the resulting 60 bhp will get you upwards of the ton in no time at all.

Probably because the 500 was the original, it benefited from a little more re-think than the other Threes, especially in the area of controls. Instead of having the idiot lights housed in individual gauges, the speedometer and tachometer on the 500 are mounted in a small, black instrument panel. Indicator lights for turn signals, high beam, and neutral and the ignition switch are located in the center of the panel.

Switches are all conveniently handlebar mounted, including a well-labeled on/off/on switch on the right. The switch housings are black and all switches are clearly labeled in orange. Besides adding to the appearance of the bike, this setup is a great aid to novice riders or those switching over from other brands.

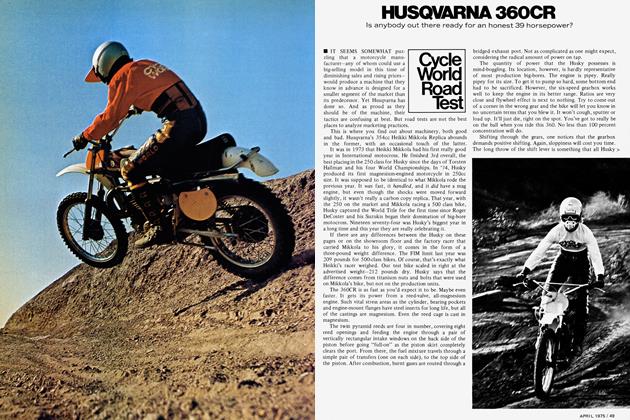

The HI, with its excellent balance between acceleration and handling impressed us a great deal, but if you place handling above all else on the priority scale, there is a better choice: the 350cc S2.

With its modest size and ample 45 bhp (at 8000 rpm) output, the S2 is one of the better roadsters for attacking curves on that favorite stretch of deserted highway. Steering is excellent. Suspension is taut. Ground clearance is ample. Add these three facts together and they equal a bike that will hold a line through a turn right up to the very limit of traction.

The S2 is especially adept through a series of sweepers. Its modest 354 lb. weight allows it to be flicked from side to side with ease. On turns with a tightening radius, just force it down >

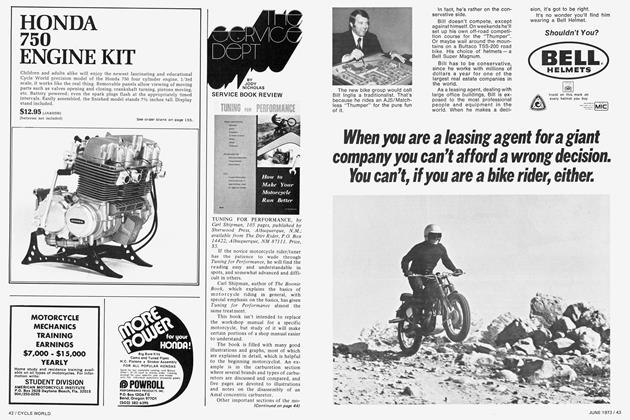

KAWASAKI

250

AND

350

THREE

$815

farther and power through.

A friction steering damper is present, but at no time did we find it necessary to tighten it down. Riding rain grooves or motoring down badly surfaced streets had absolutely no adverse affect on stability.

In keeping with its performance image, Kawasaki has fitted a disc brake to the S2. The first 350 Kawasaki Three we tested had a drum brake up front which suffered from chronic brake fade during hard use. The hydraulic disc completely eliminates this problem and at the same time exhibits good brake feel and fairly light lever pressure. The rear unit remains a drum with good feel and adequate capability.

Frame is double cradle, like the big jobs, but has been appropriately scaled down to fit the more compact S2 Three. The engine is again built along familiar Kawasaki guidelines, but shares no components with the larger displacement models.

The crankshaft is pressed together and pinned and rides on ball bearings in the horizontally split cases. Big end rod bearings are caged rollers and needle bearings are of the more conventional two ring variety, but individual barrels and heads have been retained.

Straight cut primary gears deliver 30.7 lb.-ft. of torque (at 7000 rpm) to a five-speed transmission with conventional down for low shift pattern. We personally prefer this pattern and found the gearbox excellent in every respect including shifting action and choice of ratios.

The primary technical change from the H series concerns the ignition. On both the 350 and 250, ignition is by battery and coil, and of course this system requires points to time the spark. While this system is more difficult to keep in tune, there are a couple of advantages. For one thing, it is usually easier for backyard tuners to trace a fault in a point setup and secondly, replacement parts are generally less expensive.

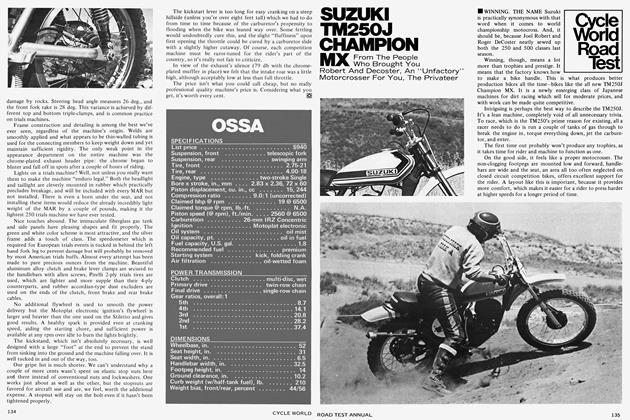

Then there’s the 250cc SI, which offers the advantage of economy of operation, although there isn’t much of a break on initial price. The SI, as is obvious from the photographs, is based on the 350 and possesses both the style and image of its near identical twin.

Performance-wise, however, they are worlds apart. Not in turns (the chassis are identical), but in straightaways and around town. The 250 is simply not very fast. There is little power below 6000 and really doesn’t come into its own until 7000 rpm or so. Consequently, some clutch slipping is required around town, especially when packing double.

Although vibration is still acceptable it is more noticeable in the bars at freeway speeds. On the other end of the spectrum, the 250 is both smoother and quieter. It’s so quiet at idle, in fact, you can hardly distinguish it over the ambient level of traffic in major cities.

Major technical differences are as follows: First, there has been a reduction in bore size from 53 to 45mm. This, of course, necessitates smaller pistons. Next, carburetor size has been reduced from 24 to 22mm, and because less power is produced, overall gearing has been lowered slightly.

The only other significant changes are substitution of a drum brake for the hydraulic discs and changing from forks with aluminum sliders to old style steel ones. As far as the brake goes, the change is appropriate and the drum is perfectly capable of halting the 250 from top speed. Brake fade is present, but not to an alarming degree. Forks on the 250, though, are not nearly as good and offer a choppy ride.

So which Three is best for you? On the surface, the choice seems difficult. Yet in reality, after all the facts are analyzed, choosing becomes an easy task. If you delight in denying opponents victory at the drags, or if your ego demands that you cruise on the quickest production 750 around, the 750cc H2 is the only game in town.

If you delight in a good turn of speed, yet demand a machine that remains predictable through a series of tricky bends, the 500 HI is a better choice. Still on this train of thought, if you place handling above straight line performance and add the requirement of nimbleness, buy the 350cc S2.

If you need to ride the bike every day but want that image, even though there isn’t enough performance to back it up, buy the 250. It offers economy of operation—something lacking in various degrees in all the other Threes.

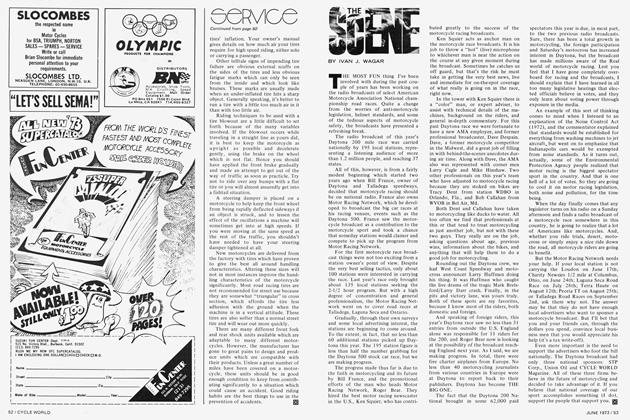

KAWASAKI

500

AND

750

three

$1475