A HOBBY THAT PAID OFF

JANE BADE

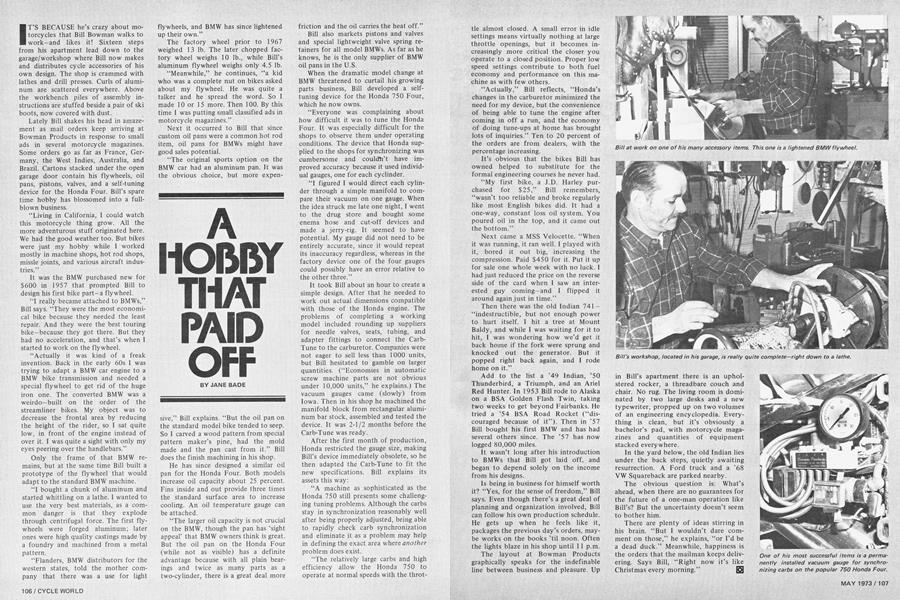

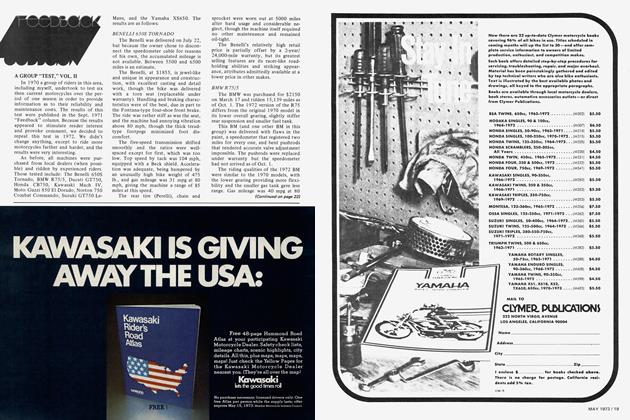

IT'S BECAUSE he's crazy about motorcycles that Bill Bowman walks to work—and likes it! Sixteen steps from his apartment lead down to the garage/workshop where Bill now makes and distributes cycle accessories of his own design. The shop is crammed with lathes and drill presses. Curls of aluminum are scattered everywhere. Above the workbench piles of assembly instructions are stuffed beside a pair of ski boots, now covered with dust.

Lately Bill shakes his head in amazement as mail orders keep arriving at Bowman Products in response to small ads in several motorcycle magazines. Some orders go as far as France, Germany, the West Indies, Australia, and Brazil. Cartons stacked under the open garage door contain his flywheels, oil pans, pistons, valves, and a self-tuning device for the Honda Four. Bill’s spare time hobby has blossomed into a fullblown business.

“Living in California, I could watch this motorcycle thing grow. All the more adventurous stuff originated here. We had the good weather too. But bikes were just my hobby while I worked mostly in machine shops, hot rod shops, missie joints, and various aircraft industries.”

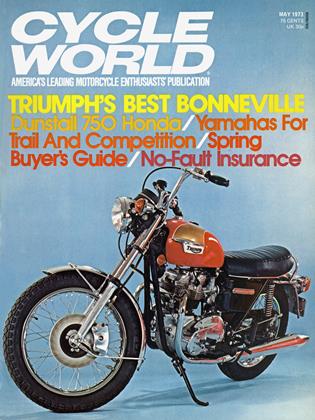

It was the BMW purchased new for $600 in 1957 that prompted Bill to design his first bike part-a flywheel.

“I really became attached to BMWs,” Bill says. “They were the most economical bike because they needed the least repair. And they were the best touring bike-because they got there. But they had no acceleration, and that’s when I started to work on the flywheel.

“Actually it was kind of a freak invention. Back in the early 60s I was trying to adapt a BMW car engine to a BMW bike transmission and needed a special flywheel to get rid of the huge iron one. The converted BMW was a weirdo—built on the order of the streamliner bikes. My object was to decrease the frontal area by reducing the height of the rider, so I sat quite low, in front of the engine instead of over it. I was quite a sight with only my eyes peering over the handlebars.”

Only the frame of that BMW remains, but at the same time Bill built a prototype of the flywheel that would adapt to the standard BMW machine.

“I bought a chunk of aluminum and started whittling on a lathe. I wanted to use the very best materials, as a common danger is that they explode through centrifugal force. The first flywheels were forged aluminum; later ones were high quality castings made by a foundry and machined from a metal pattern.

“Flanders, BMW distributors for the western states, told the mother company that there was a use for light

flywheels, and BMW has since lightened up their own.”

The factory wheel prior to 1967 weighed 13 lb. The later chopped factory wheel weighs 10 lb., while Bill’s aluminum flywheel weighs only 4.5 lb.

“Meanwhile,” he continues, “a kid who was a complete nut on bikes asked about my flywheel. He was quite a talker and he spread the word. So I made 10 or 15 more. Then 100. By this time I was putting small classified ads in motorcycle magazines.”

Next it occurred to Bill that since custom oil pans were a common hot rod item, oil pans for BMWs might have good sales potential.

“The original sports option on the BMW car had an aluminum pan. It was the obvious choice, but more expen-

sive,” Bill explains. “But the oil pan on the standard model bike tended to seep. So I carved a wood pattern from special pattern maker’s pine, had the mold made and the pan cast from it.” Bill does the finish machining in his shop.

He has since designed a similar oil pan for the Honda Four. Both models increase oil capacity about 25 percent. Fins inside and out provide three times the standard surface area to increase cooling. An oil temperature gauge can be attached.

“The larger oil capacity is not crucial on the BMW, though the pan has ‘sight appeal’ that BMW owners think is great. But the oil pan on the Honda Four (while not as visible) has a definite advantage because with all plain bearings and twice as many parts as a two-cylinder, there is a great deal more

friction and the oil carries the heat off.”

Bill also markets pistons and valves and special lightweight valve spring retainers for all model BMWs. As far as he knows, he is the only supplier of BMW oil pans in the U.S.

When the dramatic model change at BMW threatened to curtail his growing parts business, Bill developed a selftuning device for the Honda 750 Four, which he now owns.

“Everyone was complaining about how difficult it was to tune the Honda Four. It was especially difficult for the shops to observe them under operating conditions. The device that Honda supplied to the shops for synchronizing was cumbersome and couldlTt have improved accuracy because it used individual gauges, one for each cyclinder.

“I figured I would direct each cylinder through a simple manifold to compare their vacuum on one gauge. When the idea struck me late one night, I went to the drug store and bought some enema hose and cut-off devices and made a jerry-rig. It seemed to have potential. My gauge did not need to be entirely accurate, since it would repeat its inaccuracy regardless, whereas in the factory device one of the four gauges could possibly have an error relative to the other three.”

It took Bill about an hour to create a simple design. After that he needed to work out actual dimensions compatible with those of the Honda engine. The problems of completing a working model included rounding up suppliers for needle valves, seats, tubing, and adapter fittings to connect the CarbTune to the carburetor. Companies were not eager to sell less than 1000 units, but Bill hesitated to gamble on larger quantities. (“Economies in automatic screw machine parts are not obvious under 10,000 units,” he explains.) The vacuum gauges came (slowly) from Iowa. Then in his shop he machined the manifold block from rectangular aluminum bar stock, assembled and tested the device. It was 2-1/2 months before the Carb-Tune was ready.

After the first month of production, Honda restricted the gauge size, making Bill’s device immediately obsolete, so he then adapted the Carb-Tune to fit the new specifications. Bill explains its assets this way:

“A machine as sophisticated as the Honda 750 still presents some challenging tuning problems. Although the carbs stay in synchronization reasonably well after being properly adjusted, being able to rapidly check carb synchronization and eliminate it as a problem may help in defining the exact area where another problem does exist.

“The relatively large carbs and high efficiency allow the Honda 750 to operate at normal speeds with the throttle almost closed. A small error in idle settings means virtually nothing at large throttle openings, but it becomes increasingly more critical the closer you operate to a closed position. Proper low speed settings contribute to both fuel economy and performance on this machine as with few others.

“Actually,” Bill reflects, “Honda’s changes in the carburetor minimized the need for my device, but the convenience of being able to tune the engine after coming in off a run, and the economy of doing tune-ups at home has brought lots of inquiries.” Ten to 20 percent of the orders are from dealers, with the percentage increasing.

It’s obvious that the bikes Bill has owned helped to substitute for the formal engineering courses he never had.

“My first bike, a J.D. Harley purchased for $25,” Bill remembers, “wasn’t too reliable and broke regularly like most English bikes did. It had a one-way, constant loss oil system. You poured oil in the top, and it came out the bottom.”

Next came a MSS Velocette. “When it was running, it ran well. I played with it, bored it out big, increasing the compression. Paid $450 for it. Put it up for sale one whole week with no luck. I had just reduced the price on the reverse side of the card when I saw an interested guy coming-and I flipped it around again just in time.”

Then there was the old Indian 741 — “indestructible, but not enough power to hurt itself. I hit a tree at Mount Baldy, and while I was waiting for it to hit, I was wondering how we’d get it back home if the fork were sprung and knocked out the generator. But it popped right back again, and I rode home on it.”

Add to the list a ’49 Indian, ’50 Thunderbird, a Triumph, and an Ariel Red Hunter. In 1953 Bill rode to Alaska on a BSA Golden Flash Twin, taking two weeks to get beyond Fairbanks. He tried a ’54 BSA Road Rocket (“discouraged because of it”). Then in ’57 Bill bought his first BMW and has had several others since. The ’57 has now logged 80,000 miles.

It wasn’t long after his introduction to BMWs that Bill got laid off, and began to depend solely on the income from his designs.

Is being in business for himself worth it? “Yes, for the sense of freedom,” Bill says. Even though there’s a great deal of planning and organization involved, Bill can follow his own production schedule. He gets up when he feels like it, packages the previous day’s orders, maybe works on the books ’til noon. Often the lights blaze in his shop until II p.m.

The layout at Bowman Products graphically speaks for the indefinable line between business and pleasure. Up

in Bill’s apartment there is an upholstered rocker, a threadbare couch and chair. No rug. The living room is dominated by two large desks and a new typewriter, propped up on two volumes of an engineering encyclopedia. Everything is clean, but it’s obviously a bachelor’s pad, with motorcycle magazines and quantities of equipment stacked everywhere.

In the yard below, the old Indian lies under the back steps, quietly awaiting resurrection. A Ford truck and a ’68 VW Squareback are parked nearby.

The obvious question is: What’s

ahead, when there are no guarantees for the future of a one-man operation like Bill’s? But the uncertainty doesn’t seem to bother him.

There are plenty of ideas stirring in his brain. “But I wouldn’t dare comment on those,” he explains, “or I’d be a dead duck.” Meanwhile, happiness is the orders that the mailman keeps delivering. Says Bill, “Right now it’s like Christmas every morning.” |§1