BIG FLING IN UTAH

THE ANNUAL BASH ON THE SALT PRODUCED NO REAL SURPRISES

BRUCE FLANDERS

OUTSIDE NEARLY every small, country-type town you’ll find a racetrack. The locals get together and come up with a place to congregate and have a good time with their bikes. Most of these riders know the track better than they know the proverbial back of their hand. They have such a complete mastery of the track conditions that rarely does an outsider stand a chance against the cream of the local crop.

Outside the combined town of Wendover, Utah, and West Wendover, Nev., there are three tracks. To the west of this not-so-typical country town are two of the three. One is a tight, demanding motocross track, complete with a watercrossing that smells vaguely of sewage. The other is a 7-mile long hare scrambles track that retains its course markings almost all year long. If cross-country is your bag, then all you have to do is point yourself either to the north or to the west at the edge of town, and all you have to worry about is the occasional jackrabbit or barbed wire fence.

From high atop the mountains at the edge of town you can see nearly two hundred square miles of snow white salt shimmering in the sun. The freeway splits off about one-fifth of the salt, and in that portion the state of Utah has surveyed off super exact spots for racers to put down timing lights and make assaults on world land speed records.

The local riders don’t go out there very much. Most of the year it’s too wet, and the rest of the year it offers no challenge. At least no challenge is offered without the timing lights and the other activity that happens around the last week in August when the Southern California Timing Association and the AMA come to town.

The town changes from its normal facade of a highway gas stop that is

about 125 miles from Salt Lake City, and boasts six motels, three restaurants, and two casinos. Streamlined cars make engine swaps on the front steps of motels while inside the rooms, a new ring job is being performed on a Yamaha. A fever sweeps through the town and even though school starts the next Monday for the local kids, they’re up late every night taking it in like a Mardi Gras.

The local gas station becomes the workbench of Don Vesco or Boris Murray, but the local attendant doesn’t know or care because he just seems like another of them “hot rodders,” who needed a little help. It would be mind boggling to attempt to find out just how many local gas station attendants’ names should actually be listed on the sides of the cars and motorcycles as part of the pit crew who, in reality, put the vehicle into the record book as the world’s fastest.

After the Bonneville Speedweek a few of the fastest bikes stick around to make further attempts. It seems that there isn’t enough room during the regular speedweek for the really fast liners to get up to speed. They need about five miles of approach to the 1-mile trap to get up to their record breaking speed and during speedweek there is only enough room for three to four miles of approach.

The logistics of a meet with the proportions that speedweek has dictated that to benefit the majority of competitors, there should be only a 2-mile approach to three timed miles in succession. This allows 95 percent of the entries to do their thing under the watchful eye of the ambulances and fire crews. The other 5 percent must make do under these guidelines or else have a private record attempt of their own.

(Continued on page 106)

Continued from page 85

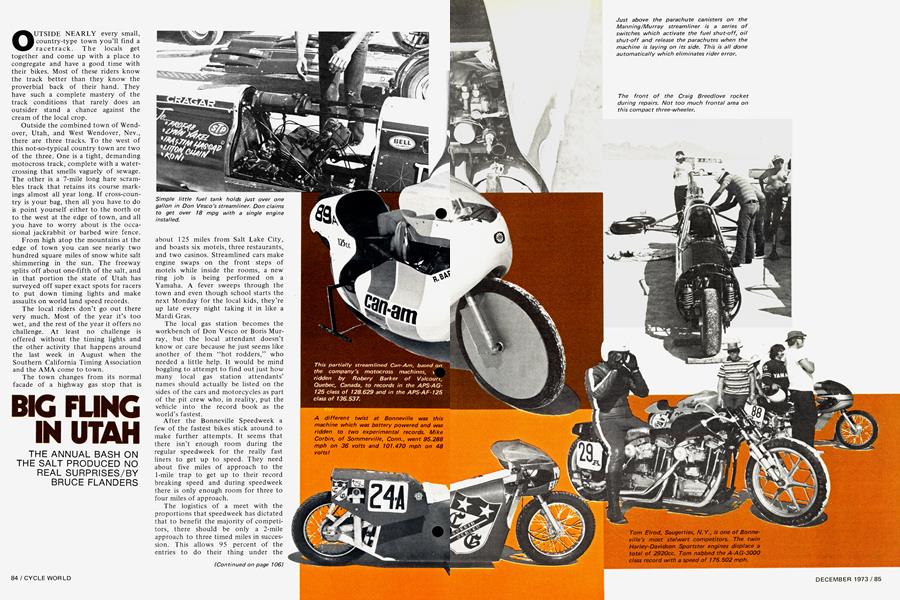

Vesco elected to stay, along with Bill Wirges and the team of Boris ¡Murray and Dennis Manning. Joining with them was the double engine Triumph of Norm Rhodes, with Jim Angerer in the saddle, and Craig Breedlove, with his rocket powered dragster.

Earl Flanders, AMA and FIM referee for land speed record attempts, took his crew and after speedweek set up the Chrondeks for these other competitors.

Breedlove was the first to get with the program and, running in some obscure FIM class that is termed rocket experimental, he unleashed a few devastating runs through the eyes, the most exciting of which was a 4.765 E.T. for a standing quarter-mile. Craig was unable to backup this run with a return because he did a barrel roll with his threewheeler. At press time Breedlove was back at the salt, still trying to get some impressive numbers.

Murray and Manning, with their double engine Triumph, did set a record for streamliners in that they were the first liner to go over 200 without having some form of a crash or lay over. Transmissions have been the weak link in that vehicle. It appears that a single Triumph trans is not set up to carry the load of two fire breathers, and in the process of proving this, Murray ate up four gearboxes.

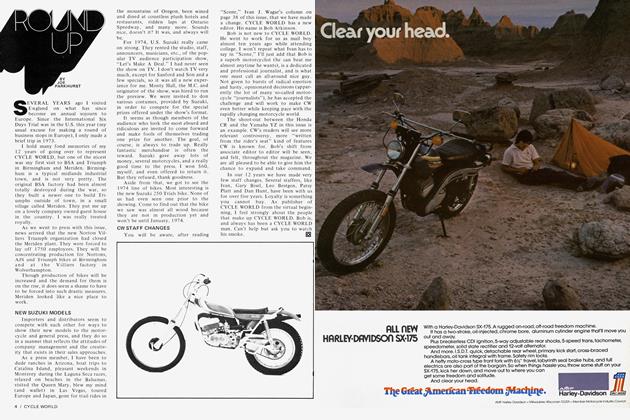

Vesco was scheduled to have two 750 Yamahas with a turbo-charger as his powerplant. Just a few days before speedweek, while testing on the dyno, it was discovered that such a potent package is actually a hand grenade in disguise. Don went after 250 and 350 international records while keeping a close eye on his competition.

Bill Wirges was the man that everyone was watching. His liner is powered by two 750 Kawasakis, and seemed to be the one that could top the 265.492 record held by Cal Rayborn in the Harley. Bill had nothing but trouble in the early stages, with either heat buildup or some form of lubrication breakdown. Runs around 247 were common but always the big one was stopped with some kind of bug.

The complete results of Speedweek should be available by the time you read this, and if you would like a copy of them and the complete rules governing land speed records just drop a line to Earl Flanders, Bonneville Nationals Motorcycle Division, Box 2297D, Pasadena, CA 91105. If any of those three liners gets the big record, and they’re still trying, you’ll hear about it in CYCLE WORLD.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue