Race Of The Americas

An International Motocross, Planned Around A Day Of Sightseeing In Lima, Peru. Riders From Nine Countries Competed—All of Them American!

Ivan J. Wagar

NO SPORT in the history of the U.S. has exploded into big time the way motocross has. This year the AMA will sanction almost 2000 motocross events from the Atlantic to the Pacific, with more than a hundred riders per event. That adds up to a lot of participants, but more important is the size of the viewing audience. About one million people will pay to spectate at motocross races in the United States this year. And, ABC’s Wide World of Sports claims 28 million viewers, making motocross the top motor sport on TV only topped in ratings by Mohammed Ali and the World Olympics!

Because of this surge in popularity, a lot of individuals have joined CYCLE WORLD (one of the very first promoters of motocross in the U.S.) as promoters of motocross, but none are more enthusiastic than Robert Booth, vice president of sales, Braniff International Airlines.

Booth, called Bobby by his friends, is a promoter, all right, but for him it’s a secondary function. Here’s how it all transpired. Bobby resides in Peru, and has two teenage sons, Robbie and Guy, who both race motocross. Their aim at this time is to enter the Rolf Tibblin School for Motocross at Carlsbad, Calif., so they can pick up all the pointers of a professional at an early stage. Add this family desire to a sojourn to a motocross race in Argentina, and the urge to promote a truly international motocross for South America with riders from all of the Latin countries and the U.S. became overpowering.

So resourceful Bobby Booth talked Braniff Airlines, along with several of his bike riding friends and well-to-do businessmen in Lima, into sponsoring his dream: The Race of the Americas. When all was said and done, a national holiday weekend was chosen, and two days of motocross were scheduled with racing on Friday and Sunday, and a day off in between for a barbecue and sightseeing. The riders’ total points from three motos each day would decide the overall winner.

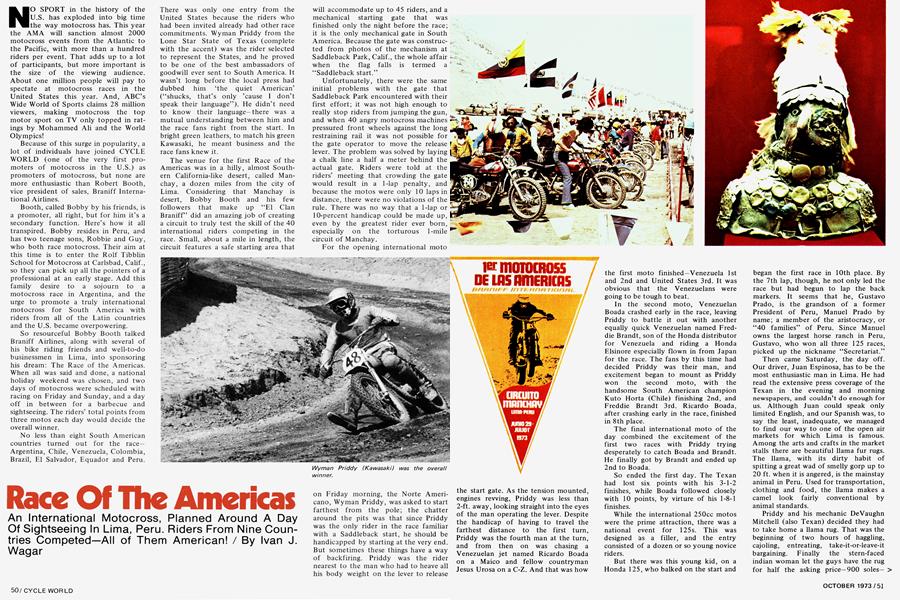

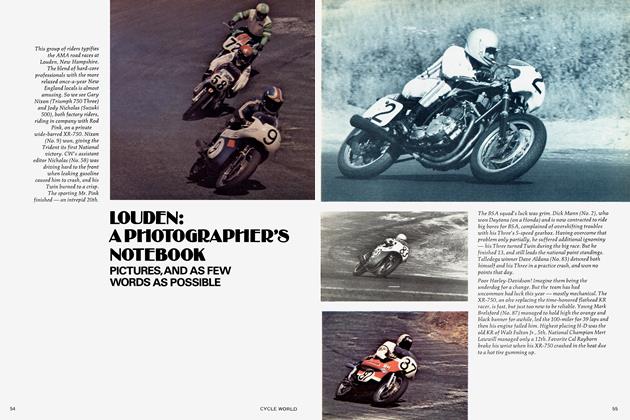

No less than eight South American countries turned out for the race— Argentina, Chile, Venezuela, Colombia, Brazil, El Salvador, Equador and Peru. There was only one entry from the United States because the riders who had been invited already had other race commitments. Wyman Priddy from the Lone Star State of Texas (complete with the accent) was the rider selected to represent the States, and he proved to be one of the best ambassadors of goodwill ever sent to South America. It wasn’t long before the local press had dubbed him ‘the quiet American’ (“shucks, that’s only ’cause I don’t speak their language”). He didn’t need to know their language—there was a mutual understanding between him and the race fans right from the start. In bright green leathers, to match his green Kawasaki, he meant business and the race fans knew it.

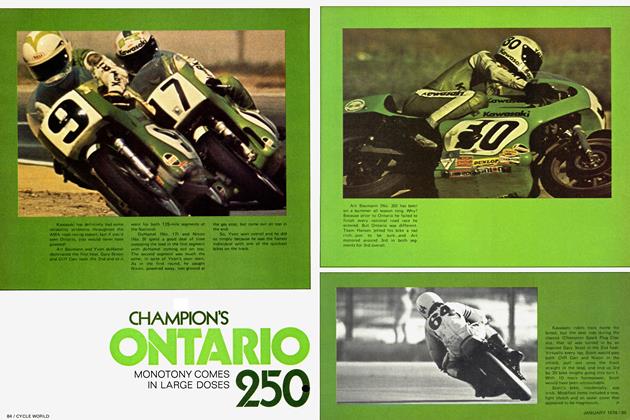

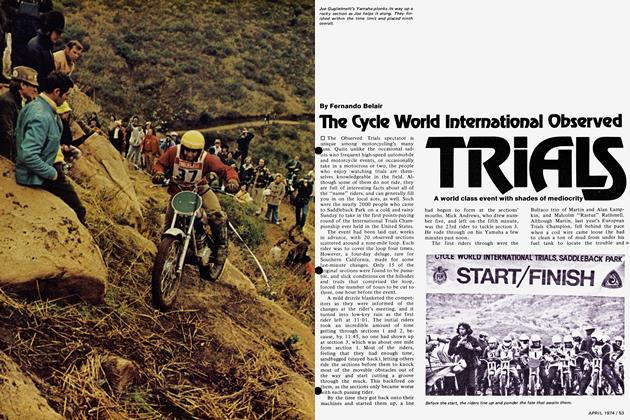

The venue for the first Race of the Americas was in a hilly, almost Southern California-like desert, called Manchay, a dozen miles from the city of Lima. Considering that Manchay is desert, Bobby Booth and his few followers that make up “El Clan Braniff” did an amazing job of creating a circuit to truly test the skill of the 40 international riders competing in the race. Small, about a mile in length, the circuit features a safe starting area that will accommodate up to 45 riders, and a mechanical starting gate that was finished only the night before the race; it is the only mechanical gate in South America. Because the gate was constructed from photos of the mechanism at Saddleback Park, Calif., the whole affair when the flag falls is termed a “Saddleback start.”

Unfortunately, there were the same initial problems with the gate that Saddleback Park encountered with their first effort; it was not high enough to really stop riders from jumping the gun, and when 40 angry motocross machines pressured front wheels against the long restraining rail it was not possible for the gate operator to move the release lever. The problem was solved by laying a chalk line a half a meter behind the actual gate. Riders were told at the riders’ meeting that crowding the gate would result in a 1-lap penalty, and because the motos were only 10 laps in distance, there were no violations of the rule. There was no way that a 1-lap or 10-percent handicap could be made up, even by the greatest rider ever born, especially on the torturous 1-mile circuit of Manchay.

For the opening international moto

on Friday morning, the Norte Americano, Wyman Priddy, was asked to start farthest from the pole; the chatter around the pits was that since Priddy was the only rider in the race familiar with a Saddleback start, he should be handicapped by starting at the very end. But sometimes these things have a way of backfiring. Priddy was the rider nearest to the man who had to heave all his body weight on the lever to release the start gate. As the tension mounted, engines revving, Priddy was less than 2-ft. away, looking straight into the eyes of the man operating the lever. Despite the handicap of having to travel the farthest distance to the first turn, Priddy was the fourth man at the turn, and from then on was chasing a Venezuelan jet named Ricardo Boada on a Maico and fellow countryman Jesus Urosa on a C-Z. And that was how the first moto finished—Venezuela 1st and 2nd and United States 3rd. It was obvious that the Venezuelans were going to be tough to beat.

In the second moto, Venezuelan Boada crashed early in the race, leaving Priddy to battle it out with another equally quick Venezuelan named Freddie Brandt, son of the Honda distributor for Venezuela and riding a Honda Elsinore especially flown in from Japan for the race. The fans by this time had decided Priddy was their man, and excitement began to mount as Priddy won the second moto, with the handsome South American champion Kuto Horta (Chile) finishing 2nd, and Freddie Brandt 3rd. Ricardo Boada, after crashing early in the race, finished in 8th place.

The final international moto of the day combined the excitement of the first two races with Priddy trying desperately to catch Boada and Brandt. He finally got by Brandt and ended up 2nd to Boada.

So ended the first day. The Texan had lost six points with his 3-1-2 finishes, while Boada followed closely with 10 points, by virture of his 1-8-1 finishes.

While the international 250cc motos were the prime attraction, there was a national event for 125s. This was designed ás a filler, and the entry consisted of a dozen or so young novice riders.

But there was this young kid, on a Honda 125, who balked on the start and began the first race in 10th place. By the 7th lap, though, he not only led the race but had begun to lap the back markers. It seems that he, Gustavo Prado, is the grandson of a former President of Peru, Manuel Prado by name; a member of the aristocracy, or “40 families” of Peru. Since Manuel owns the largest horse ranch in Peru, Gustavo, who won all three 125 races, picked up the nickname “Secretariat.”

Then came Saturday, the day off. Our driver, Juan Espinosa, has to be the most enthusiastic man in Lima. He had read the extensive press coverage of the Texan in the evening and morning newspapers, and couldn’t do enough for us. Although Juan could speak only limited English, and our Spanish was, to say the least, inadequate, we managed to find our way to one of the open air markets for which Lima is famous. Among the arts and crafts in the market stalls there are beautiful llama fur rugs. The llama, with its dirty habit of spitting a great wad of smelly gorp up to 20 ft. when it is angered, is the mainstay animal in Peru. Used for transportation, clothing and food, the llama makes a camel look fairly conventional by animal standards.

Priddy and his mechanic DeVaughn Mitchell (also Texan) decided they had to take home a llama rug. That was the beginning of two hours of haggling, cajoling, entreating, take-it-or-leave-it bargaining. Finally the stern-faced indian woman let the guys have the rug for half the asking price—900 soles— (approx. $21 American). She then broke into a smile and kissed them goodbye.

Because we spent so much time at the market haggling over rugs and looking at the beautiful but remarkably inexpensive gold and silver jewelry, we had to miss the sightseeing and go directly to a barbecue at the home of the Government Sport Commissioner Mario Suito and his very charming wife. No less than 200 people invaded the gardens of his beautiful residence for an afternoon of gaiety, feasting and bench racing.

It was quite a party, with Indian musicians and dancers giving a display of native Peruvian dances. We sampled the typical Peruvian appetizer known as ceviche, a highly seasoned raw fish marinated in lemon juice, and charcoal to hopefully take up racing in the U.S., and (hopefully) become a star outside of his native Argentina. A couple of merit badges should also be given to the El Salvador riders Harbort and Garcia for their daring exploits on virtually standard Honda XL250 four-stroke Singles, but their best efforts could not put them in the first 10 overall finishers.

Sunday’s second moto also turned out to be a Priddy benefit. Urged on by the chants of “Priddy-Priddy, Ole,” the Texan led the way for Chilean Horta and Venezulan Brandt. Meanwhile Secretariat continued his invincible winning streak by leading all of the support races with unbelievable ease.

The final moto was almost anticlimatic. Priddy had only to finish in the first five positions in order to win on total accumulated points. It is broiled anticuchos, beef heart squares prepared with vinegar and hot chili. The favorite drink was Pisco, a distilled grape brandy, and known as the national drink. Pisco sours are very popular.

Most of the attention at the barbecue was centered on Priddy and his experiences in riding against U.S. motocross stars such as Brad Lackey, Jim Weinert, Pomeroy and Tripes. Priddy left the party early, for he knew that he had to win the first moto Sunday in order to allow for any eventuality that might come up during the day. The responsibility of being the only U.S. rider in the race was a heavy burden. As Priddy put it, “They sure expect a lot from ol’ Priddy, and I sure don’t want to disappoint anybody.” Probably because of the extensive coverage of the event in the newspapers, no less than 12,000 people left the ever constant winter drizzle of Lima to bask in the hot sunshine of Manchay and to watch the lone Yankee take on South America’s best. The crowd was of an amazing size when we consider that back in Lima the soccer match (largest South American spectator sport) was Peru vs. Columbia; one of THE sporting events of the year.

Making no mistakes after a good start, the determined Priddy glided his Kawasaki to an almost easy win in the first moto, thus ensuring a comfortable start to a serious day’s racing. The crash and burn tactics of the Argentine Gilera team did not go on without notice. Racing heavy four-stroke 250 Singles against the lithe Oriental and German two-strokes, team Gilera ace rider Claudio Pesce wrestled his underpowered mount with a tenacity that made strong men weep for his survivability. Crashing hard several times, the young ace joined us on the return trip possible that the Venezuelans, had they found a way to work together, could still find a way to unseat the Texan. But, as one sage put it, “The Venezuelans fight more among themselves than they do with other people.” So there was no game plan. They all wanted to beat Priddy as individuals, which certainly would give him overall victory.

Such a ploy might have been successful, for, while negotiating a double humped knoll, Priddy found neutral on a gear change from second to third, and had the unfortunate experience of a nose dive as the second hump kicked his rear wheel into the air. The engine was still running as the Texan remounted, and worked his way back to 3rd place to clinch overall victory in The First Race of the Americas.

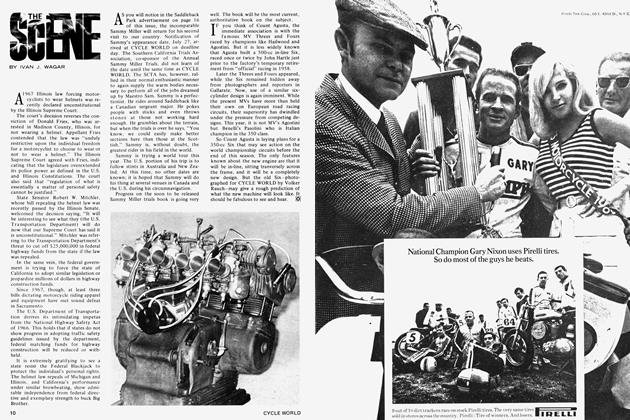

The Trophy Presentation took place in the Hotel Crillon in Lima. Guest of honor was the Mayor of Lima, Eduardo Dibos Chappuis, a very unusual mayor as he plans to race a three-litre Porsche in the 24-hour race at Daytona Florida, next February. Once a motorcycle road racer himself, he is very enthused over the sport of motocross and pleased the audience by saying he would do everything he could to support motocross in the future. Wyman Priddy received seven trophies in all, including a solid silver bowl which he wondered how he was going to get through customs.

What worried Priddy even more was how he was going to get the Kawasaki back to the States. It had taken him four hours to get it through customs on the way in because he did not have the necessary “Green Card.”

Braniff Airlines came to the rescue. But it still took Bobby Booth’s aide, Arturo Horton, eight hours to handle the paperwork. One thing the Peruvians love is paperwork. Under the military government of General Juan Velesco Alvarado, bureaucracy is at its highest level. For the ordinary tourist, however, there are no real problems. This is a country for explorers, mountaineers, and history lovers. The archeological ruins of the Incas are fascinating and make you want to bring a shovel and dig, in between motocross races, of course.

Several things are significant about The First Race of the Americas, not the least of which is the fact that riders from nine countries competed, and they all were Americans. When we consider that there was no representation from Canada, Mexico and Panama, I wonder about the participation in the next annual Race of the Americas, and the eventual popularity of motocross over soccer as a national sport in South

America.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue