Cycle World Road Test

THERE IS NO feeling as singular as a quick trip down the road on a British sports Twin that has a combination of virtues like the newest Norton Commando. Brilliant acceleration, hairline steering, tremendous braking, virtually no vibration and improved detailing and finish put this machine near the top of our “want list.”

The first Norton Commandos rolled off the production line late in. 1967, and were sold as 1968 models. These machines had a couple of novel features which set them apart from their rivals. Most significant was the frame design using “Isolastic” suspension to isolate the engine’s vibration from the rider.

Basically, the frame is fairly conventional in that it is a double cradle design utilizing a large, 2.5-in. diameter toptube which runs from the steering head back to a point under the seat. From that point, smaller diameter tubes branch out, two going back to form a loop on which the seat rides and the rear fender is mounted. Two others curve downward and eventually sweep forward to cradle the engine and finally curve upward in front of the engine and join the steering head.

The really unusual part of the frame package is the method of attaching the engine, transmission and swinging arm to the main frame section. Those items are virtually hanging to the main frame at three points, the lower two of which are resilient rubber mounts not unlike those used in automobiles to isolate the frame from engine vibration.

Superior handling characteristics are the rule because the transmission and rear wheel sprockets are always in the same plane, obviating the flexing between these two components that often occurs with many conventional frame designs during hard cornering and on rough surfaces. The problem becomes even more acute when the engine’s horsepower is high because the chain pull during acceleration tends to pull the rear wheel sideways, causing misalignment between the front and back wheels. Mistracking of the two wheels while cornering at speed is a no-no, and gives the machine the feel of an inebriated camel having convulsions.

With Norton’s arrangement there is little stress on the main frame and, consequently, thinner-walled, lighter weight tubing can be used. The total frame weighs in the neighborhood of 25-lb., light for a large-capacity motorcycle.

Another novel feature of the 1968 Commando has been retained to the present—a four-friction plate clutch with an automotive-type diaphragm spring, designed for the Commando by the Laycock de Normanville firm. With suitable actuating mechanism, it is possible to arrive at nearly twice the spring pressure of a conventional clutch without adding significantly to the lever pressure required to disengage it. For 1972 the clutch’s friction plates are grooved to expel any oil that may find its way into the area between the friction and steel plates. More than 10 scorching 100 mph-plus 1/4-mile acceleration runs were made without needing to adjust the clutch cable!

NORTON COMMANDO

The Updated Enthusiast Roadster Gets A New Classic Look, And Disc Brake, Too.

For various reasons Norton has elected to stay with the tried and true formula of a separate engine and gearbox, and they are the only British manufacturer producing machines of this configuration. The arguments in favor of a layout like this are few in number, we feel, but the system works well even though it is more costly and difficult to execute than a unit-construction engine. In order to keep costs down, Norton is constantly refining their design rather than attempting to change it completely.

The engine still retains a decidedly “undersquare” bore/ stroke ratio which has both advantages and disadvantages. Among the advantages are good pulling power at low rpm and the low complexity of the pushrod operated overhead valves which can be used because the engine doesn’t rev extremely high.

A disadvantage is rather heavy engine vibration as a result of the primary imbalances caused by the weight of the pistons and connecting rods. High piston speed is the result of a long stroke like the Norton’s, but the former theoretical maximum safe piston speed of 4000 feet per minute considered by automotive engineers to be the highest consistent with reliability has been raised considerably because of improved materials used in engine construction. At 7000 rpm, the engine’s red-line, piston speed is 4100 feet per minute.

Vertically split engine cases, often a source of complication with oil leaks, are retained on the Commando, but careful machining of gasket surfaces and the use of thicker gaskets have reduced the problem of oil leakage to practically nil.

Downstairs the Norton sports a built-up crankshaft assembly with a bolted-on castiron flywheel. Flexing of the crankshaff assembly at high engine revs due to the distance between the main bearings is inevitable, but the newest Commandos feature strengthening webs cast into the crankcase around the main bearing supports. Both mains are now roller bearings whereas previous models sported a ball bearing on the timing (right hand) side. The connecting rods still ride the crankshaft separated from the crank journals by plain bearings. A plain bushing is used at the small end, but is more than adequate for its purpose and is quieter than a needle roller bearing.

Often considered the first “Superbike,” the Commando is now offered with an engine option called the “Combat.” Our test machine had the “Combat” engine and was slightly quicker than the Commando Fastback we tested a year ago. An increase in compression ratio from 9.0 to 10.0:1, larger 32mm carburetors, reshaped inlet ports, and a sportier camshaft (taken from the 1971 production racer) are responsible for a 5-bhp gain, but mostly in the higher rpm ranges. The increase in compression was achieved by milling the cylinder head. Flat-top pistons are still used. Low and medium speed torque has suffered somewhat, but when you twist the “loud handle” in the neighborhood of 5000 rpm, it all happens! Top gear acceleration from roughly 80 mph upward is almost unbelievable, and the engine is still flexible, although less powerful, at lower crankshaft speeds.

Appearance of the engine and transmission castings has improved as an electro-phoretic finish is applied to seal the pores in the aluminum, making them smoother and keeping out dirt. The combat engine is easily spotted by its black painted cylinder barrel: the standard engine’s barrel is finished in silver to match the aluminum cylinder head.

Oil consumption problems with some pre-1972 Commandos have been lessened by fitting rubber seals to the inlet valve guides and substituting “SE” type oil scraper rings. More efficient cylinder sealing is realized by the installation of special taper rings in the second ring grooves and a simple, non-timed crankcase breather helps reduce pressures inside the engine, which were often considerable when the engine was breathed using the old method controlled by the camshaft.

The Commando’s suspension package, altered first for 1971, remains unchanged. The previous modification involved a reduction in steering trail by the substitution of different triple-clamps, and an increase in trail brought about by the larger diameter 4.10-19 front tire which replaced the 3.00-19 tire previously fitted. This change was made to take advantage of the 4.10 tire’s larger contact patch which increases cornering traction.

No steering damper is fitted to the Commando but we found an occasion to use one while performing our top speed tests. While going through a badly surfaced stretch of pavement at close to 100 mph the front end started to twitch badly, although not uncontrollably. This is partially the result of the shortened steering trail, but we’d prefer that the steering geometry be left unchanged and an adjustable friction-type steering damper be fitted. Even at low speeds, the Norton steers well, and fast swervery may be attacked with gusto without worrying when you’ll get pitched on your head. The center stand has been altered slightly for more ground clearance when heeled over to the left and the sidestand is well out of the way, hidden up behind the left hand exhaust pipe.

The Commando’s front forks are patterned after the famous Ceriani design and feature internal springs. For many years the older type Norton “Roadholder” forks with external springs were the standard for comparison, but the newer one follows well in its footsteps. The springing action was still a little stiff due to the newness of the machine, but the damping characteristics were good and getting better all the time. More than sufficient fork travel is provided for road riding, even with two aboard.

Rear suspension is handled by Girling shock absorbers with a three-way adjustable spring setting. They are well suited to the Commando’s temperment and weight, and do a superb job of controlling the rear wheel’s movements.

In spite of the American penchant for beating the other guy to the next stoplight, the Norton was primarily designed with the European rider in mind; the type of chap who values cornering ability, stopping power and high-speed cruising over raw acceleration. Commandos delivered in the States are fitted with a 19-tooth countershaft sprocket which provides improved acceleration (and reduced top speed) over the 21-tooth sprocket fitted to models for European consumption.

With either sprocket, the gearbox’s internal ratios are sufficiently close to permit keeping the engine “on the boil” when changing up. Although the coming U.S. Government safety standards will require that every machine sold and licensed have a left-hand shift with low gear at the bottom and the higher gears upward in the pattern, the Norton still retains the up-for-low shift pattern on the right hand side. Most serious road racers prefer to shift up-for-low, whether it be with the right or left foot.

Aside from a slight trace of oil at the kickstarter and gear shift shafts, the gearbox couldn’t be faulted. Crisp, positive gear changes were the rule.

We reasoned in our first test of a Commando that it would become a classic. Whether or not the machine, in toto, has become one is questionable. But the looks of the Commando Roadster are without a doubt what may be termed “classic.” Narrow, chrome-plated fenders, a not-too-large dual seat and what must be the sexiest shaped gas tank in captivity blend well into the styling scheme with the rakishly upswept megaphone-type mufflers. These keep the throaty exhaust note down to an acceptable level at full throttle, and considerably less at smaller throttle openings. The gastank is painted glossy black with a gold outline forming a panel inside which the Norton logo is displayed. The sidecovers are also painted black (as is the frame), but Norton could have left the lettering off the side panels.

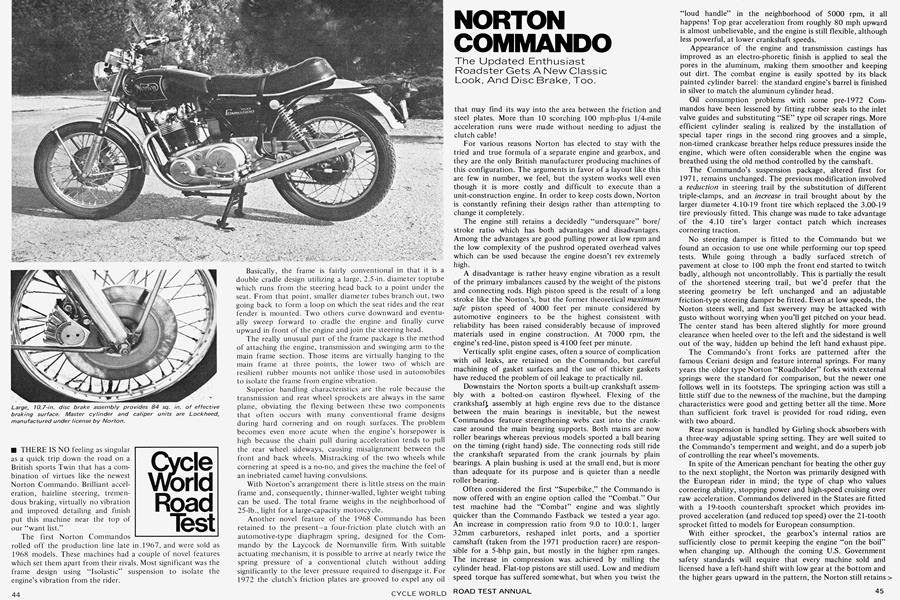

A machine capable of going as fast as the Commando must also be capable of stopping fast. There’s no problem with the new Commando fitted with the disc brake on the front wheel in getting quick, predictable stops. We couldn’t make the front brake (which performs up to 80 percent of the stopping duties) fade to any extent even after repeated stops from high speed. The brake master cylinder is acted upon directly by the front brake lever. However, as with all but one machine with a similar arrangement, it is not possible to adjust the engagement point of the lever and the brake starts working as soon as the lever is pulled. This makes getting a good grip on the brake lever difficult for a rider with short fingers which is not the most desirable thing because it still takes a firm squeeze to get a fast stop. Lightening up the lever pressure required wouldn’t be wise because it would be too easy to lock the front wheel and lose control in an emergency situation. The simplest method of overcoming this annoyance, it seems to us, would be to provide an adjustment screw to vary the point of contact between the brake lever and the master cylinder as found on the Yamaha XS-2, for example.

It’s a good thing the rear brake doesn’t have to do most of the work stopping the motorcycle, for the Commando’s isn’t very powerful and is prone to fading after prolonged usage. It is more than compensated for by the front brake, however, and it’s possible to lock the front wheel (if you’ve got a strong grip and the inclination) at any speed! The brake system is Lockheed, designed by Norton, and uses a cast-iron disc which is hard chrome-plated to prevent rust and corrosion. The cast-iron disc is much less expensive than an equivalent disc made from a stainless steel alloy, and it may be made smaller than a stainless disc because it dissipates heat more rapidly. The disc brake is the way to go.

Electrically speaking, the Norton seems on a par with any motorcycle. The Lucas components have been improved over the past few years and are gaining a reputation for quite good reliability. The coil and battery setup has been criticized by some who maintain that it is inferior to a magneto ignition at high engine speeds because the spark intensity drops off as the revs increase. However, a coil and battery system provides maximum voltage at the sparkplug for starting the engine. With a medium-speed power plant like the Norton’s, the spark at maximum engine speeds is still healthy enough to fire the sparkplugs reliably.

A spring loaded automatic ignition advance unit controls the spark advance curve from idle rpm to approximately 2000 rpm, from which point the ignition is fully advanced. A degree plate is located on the alternator rotor for timing the machine with a timing light, and is exposed by removing an inspection plug in the primary chaincase.

A wide, powerful beam is thrown by the Lucas headlight on either low or high beam positions, and Norton is the first British manufacturer to offer the new Lucas quartz halogen headlight unit as an option. That light is presently illegal for use in California, so we didn’t get a chance to try one out, but if it’s anything like the Lucas quartz halogen headlights for automobiles, it will be a winner.

Aside from the Lucas handlebar control units, which have curiously shaped blade-type switches and buttons above and below these switches, the control package was very good, with the exception of the handlebars. They are simply too high for extended high speed cruising without a windshield. The footpegs are high up and are difficult to drag while cornering. Passenger pegs are also high, but our duty pillion passengers rated the overall comfort very good. What they noticed more than anything was the almost total lack of engine vibration above idle rpm.

The Norton Commando is still the lightest and best handling of the “Superbikes,” and with the exception of not enough traction for really first class drag racing-type starts, would quite probably be the quickest as well. It is still competively priced. Continual improvement makes it even more reliable and covetable.

NORTON

COMMANDO

List price .........................$1748