KAWASAKI BIGHORN 350 F9

Cycle World Road Test

The Second Edition Is Improved With An Appropriate Carburetor, Detail Refinements. It’s A True Dual-Purpose Motorcycle.

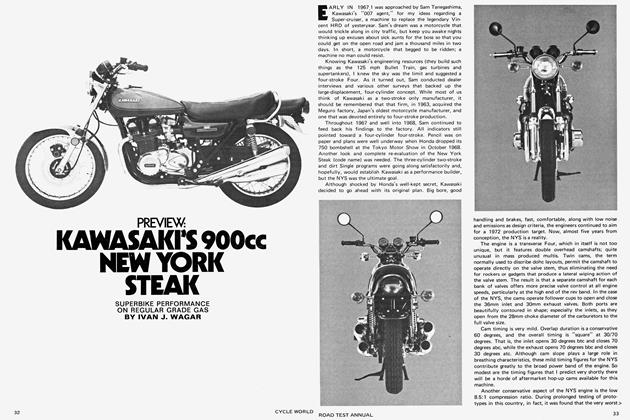

WHEN KAWASAKI INTRODUCED the Bighorn a couple of years ago, it sported more gimmicks per inch than any other large displacement, dual purpose machine on the market. Well, the gimmicks are still there, but the basic motorcycle they are bolted to is an improved machine, thanks to detail changes to the basic design.

In terms of performance, Kawasaki’s latest street/enduro, called simply the F9, differs little from the original. The changes offer increased reliability. Virtually everything that broke, bent, or fell off the Bighorn has been redesigned for the F9. Take the wheel rims, which were previously aluminum. They’re steel now. And the spokes. On the Bighorn, they were 8mm all the way; now they have been enlarged to 9mm near the hubs, the area where most spoke breakage occurs.

The most significant change, though, is the fitting of an all new, 30-mm Mikuni carburetor, designed specifically for rotary valve engines. The main difference between this and a conventional carburetor is the positioning of the floats.

Conventional carbs are designed to have the floats move in the same axis the bike is traveling. When a carburetor like this is used on a rotary valve engine, the floats are placed at a right angle to this axis, resulting in flooding or unclean running if the bike is leaned over too far. The new Mikuni eliminates this by placing the floats sideways in the carburetor body, positioning the floats conventionally when the unit is bolted to the side of a rotary valve engine.

Clean running has also been improved by modifying the automatic oil injection system’s rate of delivery. The new F9 runs considerably leaner below half throttle than its predecessor. Above half throttle, the rate of flow increases progressively until it approximates that of the earlier Bighorn at full throttle. A welcome visible result of this is less exhaust smoke. In this respect, Kawasaki is definitely on the right track.

For the most part, Kawasaki’s rotary valve Single is superb for off-road use. The only real flaw is the obvious one of engine width. With installation of the new carb, Kawasaki has further narrowed the F9’s cases to an acceptable 13 in., 3/4 in. narrower than last year’s model. While an engine width of 13 in. may not seem “acceptable” to some, it is a full 2 in. narrower than an SF350 Honda, which is in the same weight and displacement category. Still, the overhang on the right side is considerable, and a skidplate is a good idea.

Internally, the 346-cc engine differs little from the original. The crankshaft is a pressed-together unit riding on ballbearings. Needle bearings are used on both ends of the connecting rod, and the wrist pin is hard chrome-steel. Crankcases are vertically split, as before, but the aluminum side covers are painted black for better heat dissipation, and a more compact appearance.

The five-ported alloy cylinder has a new cast-in liner that warps less when the cylinder barrel and head are torqued down. This modification alone should considerably add to cylinder wall and piston life. As before, a three-ring, aluminum alloy piston allows tolerances to remain the same throughout the operating range, as it expands at the same rate as the cylinder. Four studs fasten the cylinder barrel and head to the crankcases, and the head has rubber dampers between the fins to reduce noise.

A gear drive primary delivers the power to an all new clutch. Fewer plates are used, but both inner and outer discs are thicker, which also helps prevent warping. Because of this, the unit doesn’t drag easily, and neutral is easier to engage when the machine is stopped. And, the thickness of the side thrust washer has been doubled for greater reliability.

The five-speed transmission employs the same gearsets as before, but the overshifting problem experienced on the Bighorn has been eliminated by a redesigned shifting fork. The old fork did not prevent the shifting drum from spinning after engagement, thus resulting in false neutrals between gears. To prevent this, the new fork is hooked so that it stays engaged with the drum until pressure is taken off the shift lever. It’s similar to the system used on the H1R racers, and it really works. Shift lever throw is absolutely minimal and gearchanges are precise every time. Only a slight clunk on clutchless shifts keeps the unit from being perfect.

Both the carburetor and the ultra-thin, hardened-steel rotary valve are located on the right. Care has been taken to completely seal the carburetor cavity from the outside to keep out unwanted dirt and water. As long as the bulbous rubber cover on top of the right engine case is kept intact, only filtered air reaches the carb. Previously, an idle adjustment screw protruded through this cover, but it all too often broke off. Now, a rubber plug on the front of the cavity must be removed to make the adjustment. If this plug is left out, it’s all over as far as air filtration is concerned. An unusual arrangement, but it works.

Equally unusual is the aircleaner, located under the hinged seat. Air enters the unit through louvers in the bottom third of the outer cover. From the louvers, it is directed through a wet, polyurethane foam element, and then down a central induction tube with an opening considerably higher than the outer louvers. A few inches’ more height for fording streams is thus provided. Water entering through the louvers will drain out as long as it doesn’t enter the central induction tube.

Much thought has gone into improving the F9. Even the adjustable suspension designed by Mr. Hatta has been modified. Spring and damping rates have been changed in both the adjustable forks and rear shocks. In the as-delivered position (both forks and shocks set on their softest position) the ride is a good deal softer than that of the old Bighorns. For cow-trailing at a moderate pace, this proved to be the best setting; rider fatigue is definitely minimal.

When the F9 is ridden fast over rougher terrain, the suspension can be bottomed fairly easily. Mr. Hatta’s answer to this is adjustable spring rates. All you have to do is remove the rubber plug on top of each fork leg, insert a screwdriver, and press downward while giving the slotted, cam-type adjuster a half-twist. Set the rear shocks up another notch (they are five-way adjustable) and you’re ready to try again. In this position, the ride is somewhat stiffer, and bottoming is all but eliminated on all but larger whoop de doos.

For heavier riders, another twist of the adjuster will set the forks on the stiffest position. The ride is a bit harsh for 160-lb. riders, but at least the choice is there if necessary.

For those who like to experiment, the F9’s handling characteristics can be altered somewhat by either sliding the forks up or down some 2 in. in the fork crowns, or by repositioning the front wheel in front, in the center of, or behind the fork legs.

As delivered, the wheel is mounted in the center of the fork legs, and the fork tubes extend about 2 in. above the top crown. Steering is very light, giving one the impression of being on something considerably lighter than 295 lb. Thanks to the broad powerband, the bike slides easily with the power on in either third or fourth gear. You have to be quick to get the most out of it, but generally, it is easy to control. This is definitely the setting for fireroads.

For desert, or other high-speed, rough-terrain applications, more stability can be had by extending the forks to their longest position. Steering is somewhat slower, but ultra quick steering is not a necessary prerequisite for a desert bike. Steering is somewhat heavier at slow speeds though, and this may prove a disadvantage to riders not used to such a heavy bike. Also, the forks flex too much in this position, so installation of a fork brace would be a good idea.

As for the adjustable axle, moving it forward will quicken the steering, and conversely, moving it back will make steering slower. Just because these adjustments are there, however, doesn’t mean that they are all good. Care should be taken after each adjustment until the “feel” of the machine is regained.

As mentioned earlier, the F9 feels deceptively light. The change can be attributed to a modified steering head angle which is now 28.5 deg. as opposed to 31 deg. on the earlier Bighorn. It’s easy to maneuver the F9, but steering is not as precise as we would like it. Tight uphill canyons which require hairline steering accuracy are all but impossible, and this is too bad, as the big Kawasaki is capable of climbing incredibly steep hills, as long as there is plenty of room!

Credit for this climbing ability goes to the engine. With 33 bhp and 28 ft./lb. of torque at 5500 rpm, the speed capability is there for those long sandy hills that require it. Really amazing, though, is the F9’s brute torque. True, the maximum torque figure isn’t that astonishing, but the unit will pull strongly as low as 2000 rpm in 2nd.

One of our testing hills at Saddleback Park isn’t that long, but is quite steep and too rough to take at speed. Two 360 Yamaha MXs had just failed to make the hill because rocks half way up forced both riders to shift into low. Once in low, both machines immediately dug holes, and that was it. The Kawasaki was a different story; 2000 rpm in 2nd gear with moderate wheelspin proved to be the right combination. A 500-cc four-stroke Single couldn’t have done better.

Brakes are another strongpoint. Lever and pedal pressure is light and braking action is progressive. They fade with successive stops on the street, but are still quite acceptable for a dual-purpose machine.

The handlebar/seat/footpeg relationship is comfortable, and the bars are a good compromise. They are wide enough for good control off-road, yet narrow enough for comfortable freeway cruising. This is important, as the F9 is more than capable of keeping up with expressway traffic for long periods of time.

All controls are easily reached, including the ignition switch, now located between the speedometer and tachometer. The speedometer features an odometer resettable in both directions. It registers up to 99.9 miles, and the large numerals made possible by fewer digits have proven popular with enduro riders. Handgrips are too hard though, and the throttle and choke cables are vulnerable in the event of a crash.

The seat is slanted forward too much, but otherwise provides good support. Mounting bolt diameter on the footpegs has been increased to eliminate bending, and the footpeg rubbers are secured in place with screws so they won’t fall off. This, and the chain between the rear brake lever and the frame to fend off brush are nice features.

Other items worthy of mention are the headlight, now weight saving plastic; the more heavily braced fenders to prevent cracking; the muffler/spark arrester which is quiet enough for around-town use; and the vacuum fuel tap that precludes turning the gas off when the engine is shut down.

It’s not often CYCLE WORLD tests a heavyweight that is both freeway fast and practically enduro ready. If you occasionally need a street legal machine, but would like to try some fireroading in Baja or perhaps the Greenhorn Enduro, the F9 isn’t all that bad a choice. (Data panel on following page)

KAWASAKI

BIGHORN 350 F9