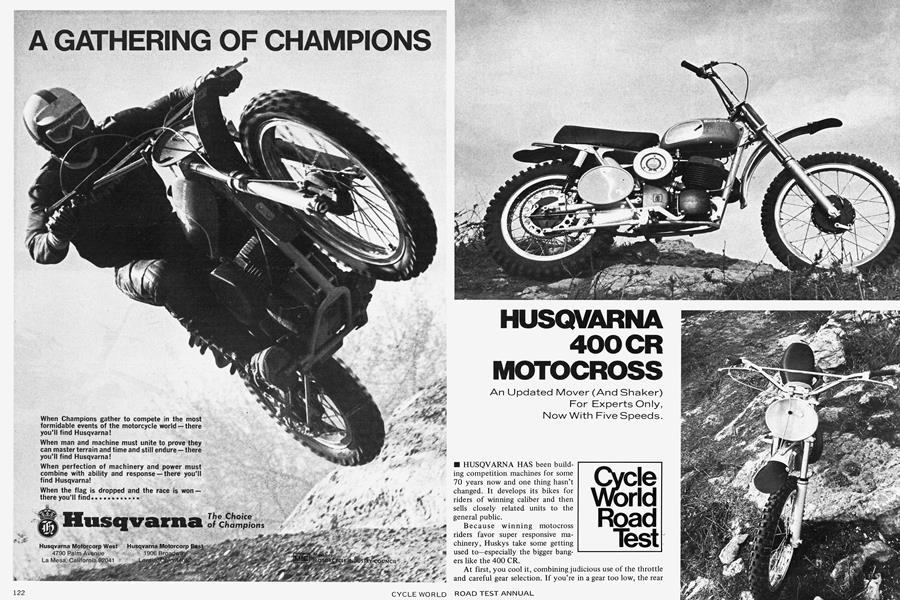

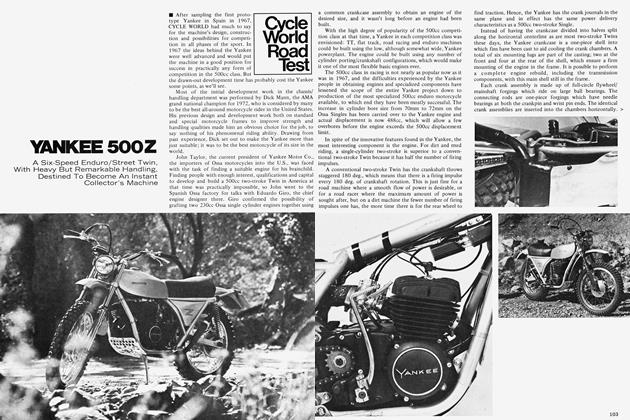

HUSQVARNA 400CR MOTOCROSS

Cycle World Road Test

An Updated Mover (And Shaker) For Experts Only, Now With Five Speeds.

HUSQVARNA HAS been building competition machines for some 70 years now and one thing hasn’t changed. It develops its bikes for riders of winning caliber and then sells closely related units to the general public.

Because winning motocross riders favor super responsive machinery, Huskys take some getting used to—especially the bigger bangers like the 400 CR.

At first, you cool it, combining judicious use of the throttle and careful gear selection. If you’re in a gear too low, the rear tire will spin violently, just like on previous big bore models. The difference with the new 400 CR is that the bike doesn’t exhibit a very strong tendency to swap ends or wheelie like the old ones.

The reason for this improved handling are some subtle changes in frame geometry. Both fork rake and trail have been altered. Fork rake is now 31 degrees instead of the 30 degrees of last year’s model and trail has been changed from 5.25 to 5.8 in. In combination, these changes slow the steering down a bit—a welcome feature for sure considering the speed and acceleration of the 400 CR.

To keep the front wheel down during acceleration, the engine has been moved forward slightly in the frame. This also helps sliding somewhat, but the rider must still be well forward on the seat for optimum control.

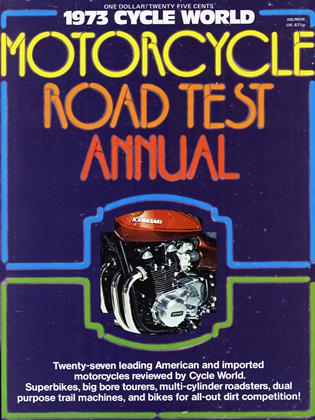

Outside of the above-mentioned changes and widening the frame slightly at the rear, the design remains the same. More than anything else, it is a clever blend of simplicity with classic design. A single toptube with an accompanying brace just below curves downward in a gentle arc behind the engine and connects to two parallel tubes which form an engine cradle. These tubes form a V at the front of the engine and are welded to a single downtube that completes the main structure. What could be simpler.

Now for the classic design features. With a 180-lb. rider on board, the swinging arm is nearly parallel to the ground and this, according to some designers, is the best possible attitude because it minimizes the torque reaction acting on the rear suspension during acceleration. In conjunction with the swinging arm, a full floating backing plate is used and the brake stay runs parallel with the swinging arm to where it connects to the main frame. Because of this, there is little tendency for the rear wheel to lock and unlock rapidly on rugged downhills that require heavy braking.

Welds aren’t as smooth as some, but the silver-grey paint is flawless and adds to the functional appearance of the machine. Fenders are polished aluminum as before, and a rubber flap on the front unit does a good job of keeping mud and other debris from flying up and hitting the rider.

Actually it would look practically identical to previous Husqvarnas except for the orange gas tank which has replaced the traditional red color scheme on the big-bore models. There is a silencer on the end of the pipe which looks effective, but in reality does little more than dull the traditional throaty Husqvarna sound. Quieter silencers are in order, but at least this is a start.

The rider is protected from burns by a large heat shield welded to the high-mounted expansion chamber exhaust. It’s OK if you are wearing high boots, but heat shielding would be considerably better if protection farther forward were provided. Still, the pipe is tucked in nicely from the large header pipe on back and doesn’t interfere with the riding position in any way.

Suspension is much like the frame package in that it is tried, proven, and difficult to fault. The front forks are internal spring units of Husqvarna’s own design. They are robust to be sure, but are not overly heavy and offer 6.75 in. of usable travel. Oils with varying viscosity from 20 to 50 wt. can be used to vary damping and to satisfy individual rider preference. Damping action is excellent.

The only flaw in the front suspension of our test bike was the fork seals. They leaked profusely from the start of testing. This was probably caused by a hardening of the seals during shipping. Fork leakage is not uncommon on Husqvarnas, however, and some riders have gone to Honda seals to cure the problem.

The rear end springs are non-progressive, but damping action and spring rate are ideal. The manual, however, suggests that you dismantle and inspect the Girling dampers regularly as the main shafts are soft and prone to bending if hit by rocks in a crash. Girlings, by the way, are not rebuildable like Konis, but do have equivalent action when in good condition.

As one might expect, both ride and stability over rough terrain is outstanding. Steering is quick, but is precise and predictable, which enables riders to pick their way through rocks and pot holes accurately at speed. Regardless of terrain the bike tracks straight and true, too—except when accelerating hard in the lower gears. Like we said, the Husky takes some getting used to, but is really impressive once you get the hang of it.

Speaking of impressive, just turn the throttle on full. Power available at the rear wheel is immense, but don’t get the wrong idea, the 400 Husky is no drag racer. Rather, it was designed! with a lot of torque and a broad powerband in mind. Select æ high enough gear in the close-ratio transmission and the big Single literally leaps between turns on a motocross course. Likewise, this particular model is not designed for high-speed dashes across the desert. The gear spread is not wide enough for that. Motocross is the 400 CR’s game.

On most bikes, a close-ratio five-speed gearset means a lot of shifting, but this isn’t necessarily true with the 400 CR. The reason is the wide powerband which eliminates an unreasonable amount of shifting on all but long straights. Once you learn the machine, exactly the right ratio can be selected.

So what does the guy who wants to ride enduros or cross-country do? For those enthusiasts, Husky makes both a 250 and a 450 with wide ratio gear boxes. Or, if you are mechanically inclined, you can substitute wide ratio gearsèts in the 400 CR as the 450 uses gears of equivalent width.

Internally, all new-generation Husqvarna transmissions are impressive. In order to save weight, and keep the unit compact at the same time, the gears are not the same width. First is quite wide, but from there on down to fifth they get progressively narrower. Fifth doesn’t need to be as strong because of lessened torque loadings in the higher gears. It is definitely clever and still strong.

Shift lever travel is decidedly long, but gear engagement is positive and missed shifts are rare. The shifting drum is hewn out of a solid block of what feels heavy enough to be 4130 steel, and should withstand repeated abuse. To keep both Europeans and Americans happy, the shifter shaft can be inserted in either the right or left side of the transmission case. Left shifting is standard, though, and an additional kit for mounting the brake lever on the opposite side must* be purchased if opposite side shifting is preferred.

The 395cc Single is in unit with the gearbox and is bulletproof, like previous Husqvarna two-strokes. Both head and cylinder barrel are aluminum alloy and the iron-lined cylinder has five ports, one of which is arranged so that it scavenges through a window cut in the piston. The piston ring is of conventional design and is hard chrome-plated to reduce wear.

A chromed steel connecting rod features roller bearings at the crankshaft and needle bearings at the wrist pin. The crankshaft, as before, rides on double-row ball bearings. Bore and stroke is 81.5 by 76mm.

With a gigantic 36mm Bing carburetor, and compression ratio of 10.2:1, a claimed 41 bhp is produced. Judging from the way the unit performs, it’s an accurate power claim.

Starting, which is relatively easy for a 400 class two-stroke, is no doubt aided by the Motoplat electronic ignition system which provides a hot spark at low cranking speeds. The system has no mechanical contact breakers and no moving parts except the flywheel. Hence, it is more reliable than conventional systems which are more sensitive to moisture and dirt. Current is interrupted in the Motoplat system by a transistor which is magnetically actuated by the flywheel via a coil. As with the conventional contact breaker system, a high-tension coil must be used to fire the sparkplug and as usual it’s mounted under the gas tank on the 400 CR.

The entire engine/transmission package is painted flat-black to help dissipate heat. The main castings are aluminum, as before, but in an effort to reduce weight, the outer covers on both sides of the case are magnesium alloy.

Cases are narrow, too, which makes the unit even more impressive. We would prefer to have the countershaft sprocket exposed for easier gear changes, but that is a matter of preference, and the outer cover in question is easily removed. Still, it makes it harder to get a derailed chain back on during a race.

With the exception of the new cog in the gearbox and the lighter cases, the big powerplant hasn’t changed all that much. But then why should Husqvarna change it? It works. In reality, Husqvarna engineers have only one serious problem left to solve and that’s vibration at high rpm. Big Huskys have always been shakers. This contributes a great deal to rider fatigue.

Vibration aside, the 400 CR seemingly has everything, including Magura controls and Akront rims. It’s a remarkable piece of engineering with self-locking nuts everywhere. It feels proper and stops as well as it goes.

Still, ride one before you buy. Few have the ability and experience to utilize all that the machine can offer.

HUSQVARNA

List price............... .......... $1380