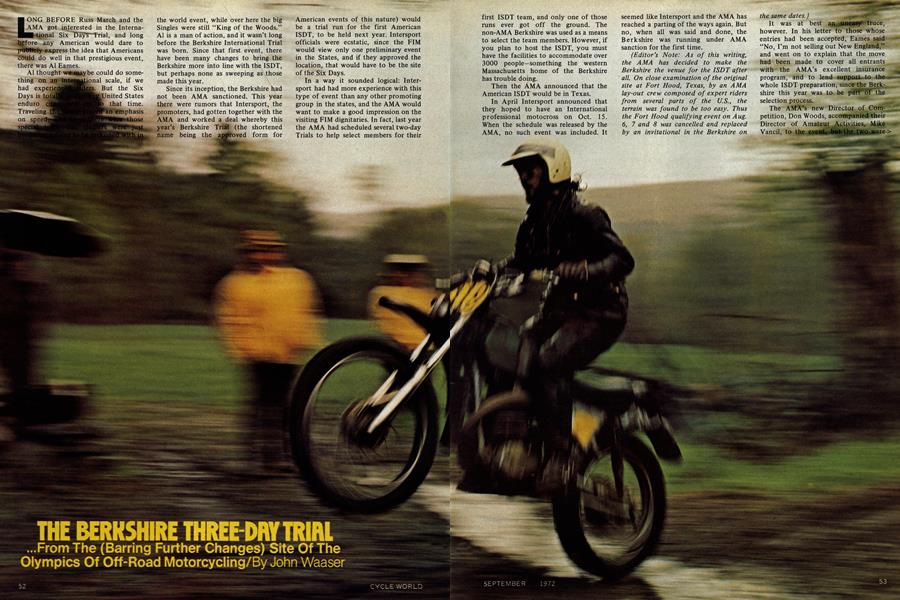

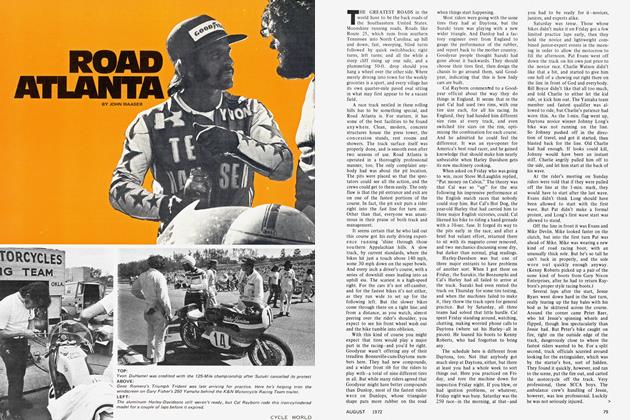

THE BERKSHIRE THREE-DAY TRIAL

COMPETITION

...From The (Barring Further Changes) Site Of The Olympics Of Off-Road Motorcycling

John Waaser

LONG BEFORE Russ March and the AMA got interested in the International Six Days Trial, and long before any American would dare to publicly express the idea that Americans could do well in that prestigious event, there was Al Eames.

Ai thought we may be could do something on an international scale, if we had experienced riders. But the Six Days is totally unlike any United States enduro conducted up to that time. Trave1ing the roote placed an emphasis on speed,and then there were those speciar test,the tiddlers were jus becoming a force to be reekonded with in

the world event, while over here the big Singles were still "King of the Woods." Al is a man of action, and it wasn't long before the Berkshire International Trial was born. Since that first event, there have been many changes to bring the Berkshire more into line with the ISDT, but perhaps none as sweeping as those made this year. Since its inception, the Berkshire had not been AMA sanctioned. This year there were rumors that Intersport, the promoters, had gotten together with the AMA and worked a deal whereby this year's Berkshire Trip (the shortened name bemg the~d form for

American events of this nature) would be a trial run for the first American ISDT, to be held next year. Intersport officials were ecstatic, since the FIM would view only one preliminary event in the States, and if they approved the location, that would have to be the site of the Six Days.

In a way it sounded logical: Intersport had had more experience with this type of event than any other promoting group in the states, and the AMA would want to make a good impression on the visiting FIM dignitaries. In fact, last year the AMA had scheduled several two-day Trials to help select members for their first ISDT team, and only one of those runs ever got off the ground. The non-AMA Berkshire was used as a means to select the team members. However, if you plan to host the ISDT, you must have the facilities to accommodate over 3000 people—something the western Massachusetts home of the Berkshire has trouble doing.

Then the ÁMA announced that the American ISDT would be in Texas.

In April Intersport announced that they hoped to have an International professional motocross on Oct. 15. When the schedule was released by the AMA, no such event was included. It seemed like Intersport and the AMA has reached a parting of the ways again. But no, when all was said and done, the Berkshire was running under AMA sanction for the first time.

(Editor’s Note: As of this writing, the AMA has decided to make the Berkshire the venue for the ISDT after all. On close examination of the original site at Fort Hood, Texas, by an AMA lay-out crew composed of expert riders from several parts of the U.S., the terrain was found to be too easy. Thus the Fort Hood qualifying event on Aug. 6, 7 and 8 was cancelled and replaced by an invitational in the Berkshire on the same dates.)

It was at best an uneasy truce, however. In his letter to those whose entries had been accepted, Eames said “No, I’m not selling out New England,” and went on to explain that the move had been made to cover all entrants with the AMA’s excellent insurance program, and to lend support to the whole ISDT preparation, since the Berkshire this year was to be part of the selection process.

The AMA’s new Director of Competition, Don Woods, accompanied their Director of Amateur Activities, Mike careful to steer clear of the promoters, and Vancil even made sure he didn’t wear his Peacock uniform around the fairgrounds.

It was revealed that AÍ Eames would be called upon to do much of the ISDT layout next year for the AMA, due to his Berkshire experience. There was a sign posted to the effect that AMA memberships were available inside the headquarters building, and that Intersport officials were selling these memberships. The AMA Directors insisted that Intersport was being very good about selling $7 memberships, but David Sanderson, editor of Indiana Motorcycling News, noted that at no time was he asked to show a membership card or Competition License, and Intersport officials candidly admitted that they weren’t checking AMA memberships.

The other major change this year was that the event was extended to three days. There were rumors of this impending change following last year’s event, but at that time Eames had indicated that the logistics of running a three-day event here were impossible. Following the 1971 ISDT, however, AÍ made up his mind to go for broke and run the event as a three-day Trial this year, making the Berkshire the first announced three-day event in the country. Perhaps even then he was thinking of that FIM-viewed preliminary event, which must be of three days’ duration.

Intersport describes the Berkshire Trial as “a major motorcycle sports event conducted for its own rewards as a sporting occasion for motorcycle trail riders.” They do not attempt to make any money with it, and they take great pains to avoid any hassles with the public.

In fact, organizer Eames is so concerned with ecology that he has cancelled his second event, the Hinsdale Enduro this year, to give the ground a rest. For the same reason, they decided this year to limit entries to 300, though in past years over 400 riders have contested the event. This year, for the first time, no novice enduro riders were permitted to enter. Rare indeed is the novice who has finished any previous Berkshire, and it was thought that the third day would really kill them.

One official noted a trend among enduro promoters to kill the green rider in the first 10 miles, so that he’ll never come back. The sport is growing so fast that the organizers can’t handle all the novice applicants. New England has a system—before you enter your first enduro, you have to go to school; then you earn points at each event to move from “C” class (novices) to “B” class; and finally “A” class. Intersport was

accepting only “A” graded riders and “B” riders, or those with AMA “A” cards.

And why should the organizers have to be so restrictive? What great prize awaited the finishers? A slip of paper, that’s what. A little document that says that the winner is entitled at some future date to a medal.

Those with perfect scores and a high enough score on the special tests get a gold medal. Those who lose fewer than 25 enduro marks over the three days, and whose total elapsed time for the special tests is not more than 50 percent longer than the fastest rider in their class get a silver medal, and those who struggle through the run without arriving more than an hour late at any checkpoint, and who achieve a recorded score on the special tests, get a bronze medal. The greatest prize by far is the knowledge that you beat the land and finished. Satisfaction. Ego. Advertising value.

The start of this year’s event was back at the Middlefield Fairgrounds, deep in the heart of the Berkshire woods, where it had been two years ago. The area' is primarily used for the county fair in the summer, and cowflops abound. Careful where you step. The plumbing gets pretty primitive, too, but there’s lots of woods.... The damp smefl of the buildings indicated that this was their first time in use this year.

Camping at the fairgrounds is for entrants only. Those who were here two years ago knew the secret; camp on the rocks to avoid the hopeless mud. Signs were posted banning fires on the grounds. With that many tents around, one spark could start a disaster, and the only water available was what little was on the tank truck kept full by the local fire department. No numbered routes lead into Middlefield; any fire would rage out of control before a larger fire department could make it to the scene. The Hinsdale Lions Club has provided excellent food here in the past at reasonable prices, and they were here again this year—though somehow the fare didn’t seem as good. The stand outside was featuring hombergers— which seemed nothing more than skinny hamburgers, and were OK if you like hamburger rolls. I settled for hot dogs. Sunday’s chicken dinner was about the best they offered—all you could eat for $2.50.

Eames has developed a reputation among enduro organizers. His relationship with the country folk is certainly to be coveted. This year as we parked for a spectator point on Friday, a local car drove up. “What’s the trouble?” inquired the little old lady. “Nothing,” I replied, “just a motorcycle enduro passing through this point.” “Oh,” she exclaimed, “I thought that was tomorrow. It’s always Saturday and Sunday isn’t it?” Here he’d caught her by surprise, and she’d miss seeing those guys struggle through the woods. Damn!

In an effort to increase this goodwill with the locals, Intersport has, for the last two years, run a sound test on all machines. This year no machines would be accepted into the paddock the afternoon before the event unless they went through the Scott sound meter at less than 88db on the “A Slow” scale under full throttle, second gear acceleration at a distance of 50 feet. “We mean business on this noise thing,” said Intersport, adding, “This limit will accept all trail bikes fitted with the stock manufacturer’s mufflers unaltered and firmly in place.” It’s tough, however, to control the distance. Riders had to run their bikes along a paved road, and the meter was held 50 feet from the center of the road. Those who rode 10 feet either side of the center could affect the reading by several db, and the organizers didn’t seem to bother them much.

The only bikes having much trouble with the test were the Husqvarnas; the guy on the meter is a former Husky owner himself, but Jack Lehto, who heads their Eastern distribution network, claimed a foul. He said that the meter was turned up to the 90db scale for Huskys, and that if the bike didn’t move the needle they made him go through again and twist the throttle harder. Everyone knows Huskys are noisy, but Jack said he wanted to be treated the same as everybody else, and on the same scale.

Most of the Huskys went through at just over 90db. Intersport had already published the results of tests which showed that rubber plugs in the Husky cylinder fins would cut the noise output by 3db. They practically insisted that all the Husky riders insert plugs in their fins. In every case the output fell by 3db, and officials were happy, even if Jack wasn’t. Somebody cracked that the Husky riders would flunk the sound test on their mouths alone, and that did nothing to soothe feelings. Dave Sanderson rode a Husky, and had strung a bead of silicon bathtub caulking across the tops of the head fins, good for another couple of db, with no loss in cooling ability (as far as he could determine).

The tactory Dalesman bikes had a new exhaust system made by Volumetric Efficiency. But, while the system boosted power quite a bit (George Peck thought it was good for about 4bhp, going from about 12 to 16 at the rear wheel), it was noisy. The noise was not coming from the tip, either, but resonance from the sides of the system. At 88db, it was just legal, but not quiet enough to suit Ron Jeckel, the importer, who noted that the exhaust on the new Pentons was routed through fiberglass to quiet just such resonance. Dalesman rider Bob Hogan had the old system, and went through at 85db, but had they held the meter on him as he > braked at the end of the run he might have flunked.... His brake squeaked at a very annoying pitch.

All of the new Spanish bikes are quiet. These three manufacturers (Montesa, Bultaco, and Ossa) have really taken the noise thing seriously, and they seem to have done so without any appreciable power loss. One Montesa went through at 85db in a full wheelie. You can’t argue with that. The Hondas, of course, were almost inaudible. And that you can’t hardly argue with, either.

“Cheating to gain any prestige from a win or a finish is just a cheapening of the objective of taking part,” said the rules. Traveling route marshalls were employed to ensure that nobody broke any rules.

This year one of the marshalls made it his business to follow one support crew member.

It’s said the crewman moved his last gas stop on Saturday a total of four times when route marshalls kept popping up. And Ed Friend, who was in charge of the marshalls, saw one rider make a left hand turn at a point where the route went straight. He followed, and came across the bike stopped by one of the support vehicles.

He stopped and chatted just long enough to inform those at the scene that he was a route marshall, whereupon the rider remounted and hastily rejoined the route. This is precisely the sort of cheating which goes on at the ISDT, but nobody gets caught. The AMA has disavowed this sort of thing, and indicated they will try to win without it.

Privateers weren’t above doing a little cheating, either. One rider was caught red-handed at the back of his van with the van doors open and a huge rollaround toolbox right inside. He insisted he didn’t know that was illegal. He didn’t finish, so it didn’t matter. Intersport had promised instant disqualification for anyone caught cheating, but failed to invoke any penalties. They later said that nobody was caught cheating, just in the process of getting ready to do so.

The rules stated plainly that any tools or parts must be carried by the rider. No outside assistance could be received in these areas. At Saturday’s third check I watched the occupant of a Rover 2000 lay some tools on one man’s machine. “Here, you found these on the ground,” said the benefactor. This sort of thing went on all the time, and it wasn’t really the sort of thing Intersport officials were interested in ferreting out. What they wanted to stop was the use of a team of mechanics to carry out repairs while the rider rested. “You have no idea how much five guys can do to a bike in one minute,” said one official.

To prevent the changing of major parts, such as wheels, engine cases, and the like, these parts were painted with a special paint, as is done in the ISDT. But the paint used looked like it could have come right from the spare parts department of Penton Imports, so closely did it match the blue of the factory bikes. (Blue is the official United States racing color, though this particular shade looked a lot more like French Racing Blue.) Intersport officials insisted that the two colors were different, and that they could tell the difference. Perhaps they could, but I sure couldn’t. One local rider took great pains to get some of the paint on his hands while his bike was being painted, and then he went out to match the paint, and walked around the pit area with a set of wheels and other parts marked with his paint, which was a much worse match than the Penton color.

To prevent any upper end work, the cylinder barrel was sealed to the head with wire and a lead seal. All competitors were instructed to drill holes through the head fin and the top barrel fin to facilitate this. Ossa heads have a horizontal fin below the vertical fins, which may at first appear to be the top barrel fin, though it is part of the head. Barry Higgen’s Ossa had the holes properly drilled, through the two head fins, and the top barrel fin. But Intersport officials ran the wire through only the top two holes, so that the head was sealed to itself, and could be removed at will. Barry never got the chance to make use of this mistake, as his bike went out the first day with a burned wheel bearing....

Ron Jeckel had just passed inspection when Chuck Hemlow, the starter, noticed that one of Ron’s tires had a crack in it. The rules were bent to allow Ron to change the tire under the watchful eye of a scrutineer, since the tire was a “safety-related item.” Other competitors quickly thought of changing other such items, without a time penalty, and Intersport apparently quickly rescinded the rule change. Jeckel took quite a while, since he pinched the tube, and had to install a second new one. (Eames had “filed” an AMA request that he include a timed tire change as a special test....)

Minimum production rules, of course, don’t apply to enduros, and anything, including prototype machinery, is legal. Tom Clark, who used to be the AMA’s Director of Professional Competition, has found himself a niche at Rokon, and he was one of two riders entered on Rokon prototypes.

The bike uses a snowmobile engine and belt drive, with a continuously variable ratio. Another prototype also had what is basically a snowmobile engine. Jeff Smith had the Bombardier 125 there. This machine uses a rotary valve, with a long intake passage casting which allows the carburetor to be mounted behind the cylinder, yielding a narrower engine. Great for low-end torque, of course, but Jeff won his class at the recent Intersport professional motocross at Pepperell, so the thing obviously works well at most speeds.

And Bud Peck headed a team of entrants on Ducatis. The big Single is truly not yet dead, so take heart, members of the Gold Star Club.

These bikes sported a variety of exhaust systems, and in spite of the noisy valve gear common to Ducatis, they were all fairly quiet. Lean, narrow, lighter than most big-bore four strokes, they formed the last refuge for a certain type of rider. When George Peck’s Dalesman ingested a large quantity of mud, they hooked onto it with one of the retired Ducatis, and pulled it out of the woods. “George never went so fast on that bike,” they said. “Nor so hairy,” noted George, telling of the sort of ride you get when power is being applied not to the rear wheel, but to the handlebars, and the front wheel dips into frequent holes. The bike tends to endo, the rear end coming up above the front axle each time....

In addition to the Ossa rear ends, Chemglas, in Ashburnham, Mass., makes a 31/2-gal. gas tank for Yamahas, one of which sits on the writer’s own machine.

I couldn’t get used to the looks at first, but when I sat on the bike I could tell the difference immediately. The rear of the tank conforms exactly to the front of the seat, giving a natural position for the knees, and ensuring a smooth ride up the tank on those occasions where control is totally out of the question. No ruptures. Great!

The Japanese are really getting serious about the woods bike market. It’s getting so that no Yamaha need be mentioned along with unusual machines. But Suzuki, Kawasaki, and Honda? That’s a different story.

Joe Barker, of Belpre, Ohio, came to the Berkshire with a stock Suzuki 185cc woods bike. He’d finished the Lonesome Pine and one other enduro on the bike, and here he was taking off on the third day still in the running for a gold medal. Unfortunately the Berkshire mud took its toll on his brand new chain and sprockets, and he dropped out some 30 miles from the finish when the chain started slipping so badly he couldn’t drive it even on the road. Had he carried a spare countershaft sprocket, he could have made it. He said that he had been unable to locate any decent chain, and was running the stock item; he was surprised to hear that an accessory firm was selling the new Litton chain at the fairgrounds....

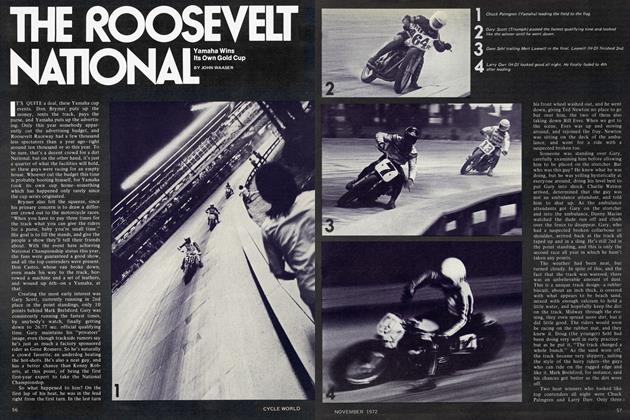

Kawasaki was represented by Manley & Sons, the Canadian distributor, who > brought a team comprised partly of former top European motocross stars now residing in Canada. The bikes looked box stock, but had been carefully fitted to the individual riders. They passed the sound test with ease, started readily, and looked neat. However, only one of the bikes finished the run, in spite of the professional caliber of the riders involved.

Honda was “unofficially” involved. They were “helping” Dave Mungenast to develop the new 250. They also helped Husqvarna take the club team trophy—Ron Bohn had a team entered in the Club Team competition, and one of the riders couldn’t make it. Mungenast had entered on a Husky, so signed on as a replacement. Meanwhile he made the deal with Honda, and rode the bike to a gold medal, helping Bohn win the trophy. Husqvarna also won the trade team trophy, where the use of a Honda would doubtless have been frowned upon.... Dave got his gold in spite of a couple of problems with the bike—like riding the last 55 miles on a flat front tire. That’s riding!

Again this year, Intersport was using Japanese-made Amano time clocks to punch competitors cards at the checkpoints. This can make it a bit rough at times —you have to get your card punched on your minute, not just get the bike to the flag on time.

For this reason Intersport allowed a minute’s grace at each check before calling a penalty. Each competitor carries his own card, and is responsible for it. Loss of a card means an automatic reduction to bronze medal level. Losses are not cumulative; that is, if a competitor is late to a check, he does not have to make up that time on the next leg in order to avoid a second penalty for it. This way, when the competitor gets in, he hands his card to the organizers, who merely subtract to find the number of minutes he took for each section, then compare the figure with the correct time. Sure beats looking for each individual’s time on a master card kept by the checkers.

Thus Intersport can get the results out within an hour after the last man is disqualified for lateness. Instead of breaking ties by timing the riders to the nearest second, they use special tests— which are nothing more than flat-out races through the woods; a hillclimb, a cross-country, and a speed test.

Points here are the rider’s elapsed times through the section, and the lowest score wins. Here is where a faster bike can mean the difference when you’re going for the overall trophy. To determine individual medal winners, each rider’s time is compared to the fastest man in his class. But there is no

weighting used in going for the overall trophy. Tests are not looked at individually, either, but the total score for all tests is used, so that one bad test should not drag down a fast competitor, unless it raises his aggregate time more than the allowable amount.

“Think it’ll start?” Bud Peck called out to starter Chuck Hemlow on Friday morning. “It’d better,” replied Chuck. It did, taking just a bit longer than some of the other machines on his number, but quickly enough so that Bud got the Due roaring off down the road within his minute. One of Friday’s spectator points was a giant hill. Going up wasn’t bad, but getting down the other side proved the downfall of many riders.

Billy Dutcher wasn’t competing this year, so he had agreed to run a route check—a point where the riders must stop to have their cards signed, though no times are recorded, just to ensure that the rider has not cut out a difficult section. (A few of these guys know the terrain almost as well as Eames by now....)

Billy had borrowed a Bultaco Alpina for the occasion, and rode it down to the check. When he decided to go back to the truck for the beer, he found he couldn’t make it back up. The only way out was to follow the course after the riders had gone through; he walked back for the beer....

One rider referred to the large number of spectators as a “crowd of sadists.” Another asked “Did you put all these rocks here?” Dave Eames (Al’s son) was riding the event on his new Yankee. At the top of the hill the rider in front of him stopped and gingerly looked for the best passage. “Come on,” yelled Dave impatiently, “it won’t bite.” Yankee’s advertising manager, Norm Goyer, was standing right there at the time. “Oh yes it will,” he replied.

Later that afternoon the run included a traditional gas stop; Sauerwein’s BP station in Becket. Inside the building there was Mrs. Eames, working behind the counter, because the proprietress had been too ill to be up to it. To run an enduro these days, you have to be able to do anything.

Saturday morning, it’s “up and at ’em” bright and early for those still in the running. The first rider picks up his machine at 7:45 for 15 min. of repair time, then it’s off at eight. This morning it’s raining. But that’s nothing new for the Berkshire. When your number comes up you must start the bike and cross a line 75 feet away within one minute, or have 20 points added to your special test score.

Jeff Smith, the former World Motocross Champion, was still working on his Bombardier as his minute came up, but he quickly left the tools at the feet of one of the Kawasaki support crew standing outside the fence (these Canadians stick together) and pushed to the

line, started his bike, and crossed the penalty line—all within his minute. The tools miraculously were to disappear later, to be returned to Jeff at some future time.

Stan Shirah’s DKW started on the first kick, but then took more than a minute to run clean enough to handle a start. It could have been more exasperating than it was, but he was already over the minute when he got to the line. The first part of the route was fairly easy, and an extra three minutes had been tacked onto each check to make the going easier in the mud.

Riders arrived at the third check super early; most were still raring to go, and at this point had just come onto paved road from a narrow woods trail. They just screwed it on; many didn’t seem to see the check. “They don’t know what a yellow flag means,” said one official. Paul Lussier was one of those. It is taboo to go past the check without checking in, so Paul hit the binders hard, just as he was alongside the clock, and the machine went down with much loud clattering and banging, though no damage was done.

Norm Goyer was standing in the woods at this point, ecstatic over the fact that the Yankee team was the only team left intact. If they could finish the day, they would win the team trophy, regardless of what happened on Sunday. Before Saturday was over the whole Yankee team would be out, except for the alternate, which some people thought was poetic justice of a sort....

What was putting the riders out? Dick Burleson, whose loss was at first viewed as total disaster to the Penton effort, broke a dinky ignition wire, and went over his hour (was disqualified for lateness at the next check) trying to locate and fix the problem. Matt Weisman (Penton’s ad manager) was riding a Puch and lost his chances for a gold when the air box filled with water, and he didn’t realize that there was a drain provided for just such emergencies.

Lars Larson, of the Husqvarna team, lost his fire; he had spark, gas and compression, yet they couldn’t even get a pop out of it. Jeff Penton said they thought it could be a turned flywheel, putting out sparks at the wrong time.

Malcolm Smith was also a member of the ill-fated Husky team. He lost the rear wheel nut and washer, so that his rear wheel was jumping back and forth in the adjustment slot, creating a variable alignment problem. Malcolm’s just not used to that sort of thing, and didn’t feel comfortable at speed. He stopped and pinched a pair of visegrips over the axle. Resourceful, eh wot?

It worked, and Malcolm stayed on time the rest of the day, losing no enduro point in the process. Unfortunately, the problem occurred during the Saturday speed test, and the time spent (Continued on page 109) fixing it brought his cumulative special test score total up over 25 percent above the fastest time in his class, which reduced him to silver medal status in spite of his perfect route score.

Continued from page 60

A brilliant team manager might have ordered his other riders to take it slow on the remaining tests had this occurred in the ISDT, but here there was only one test to go. And to get away with that, you have to be sure that nobody else can traverse the tests as fast as your riders can.

If the fastest rider’s score had been a bit higher, Malcolm might have achieved a gold, but if, say, Ron Bohn had overcooled it, he could have lost the overall win, and that just somehow doesn’t seem worth it from a team standpoint, either...especially with one team member already retired, and the chances of taking the team trophy diminished by that fact. And Bohn was actually riding on another team and owed nothing but brand loyalty to the Husky crew.

Jeff Penton had another interesting special test problem. He had entered on a 175cc Penton, but switched to a 125 for the event. Since he entered the 250 class, he was scored with the quarterliter machines, instead of the 125s. Had his score been faster than his brother’s, he still would not have won the 125cc class. Had he had a problem like Smith’s, the difference in which time his own time was compared with could have made the difference between a gold and a silver.

Charlie Vincent was the first of the Yankees to retire, with a shattered clutch basket. Charlie’s machine was actually a highly experimental version, using such oddities as a 15-degree crank instead of the common 360 job.

This gave a firing impulse much like that of a V-Twin, and any Harley owner can testify what that does for power delivery. Supposedly it smoothed the engine out, to boot.

All the rest of the Yankees succumbed to the Berkshire mud. The mud here is a bit different from most of the mud you’ll see; it contains a lot of grit which wrecks havoc on anything and everything. The Yankees were running too-short shock absorbers in the rear; hasty replacements while the originals were being rebuilt. The rear tire abraded the inner fender, making holes through which the mud traveled into the air boxes. More mud got in from in front, under the seat.

When they discovered this, they made a fast trip to Schenectady Saturday night, and fabricated a shield out of plastic rug runner, to keep the mud out of the one remaining machine. When they pulled the seat Sunday night Dave Eame’s filter was much cleaner than it had been Saturday night. The shield probably kept Dave from joining his teammates in the graveyard. The mud also chewed up brakes, chains and sprockets at an unbelievable rate. Notching the sprocket teeth to give the mud a chance to “sork” out from between the chain and the sprocket was a popular dodge, but it didn’t always work a hundred percent. Worst sprocket of the day was Joe Barker’s, on the Suzuki. You couldn’t have gotten it more round with a centerless grinder....

(Continued on page 110)

Continued from page 109

The Dalesman bikes were breaking the rear frame behind the shock absorber mounts. Once the frame broke, mud got into the air box, and put the machine out unless a shield was fabricated. The most disappointed rider in the entire event had to have been Dalesman importer Ron Jeckel. Well after the halfway point on Sunday, Ron had still zeroed everything, and seemed certain to score a gold. At the top of Sunday’s timed hillclimb, the transmission cluster key let go, and he dropped out, two hours from the finish. Guess those Sachs tranny problems aren’t really cured yet. Jeff Penton eyed the little tubes coming out of the Yankee frame to protect the shift levers covetously; he had to do a shifting adjustment on his own bike after a spill.

The rain was predicted to continue through Sunday, but shortly before start time the sun broke through the clouds to reveal a beautiful New England Spring day. When asked about the weather, Jeff Penton replied that it “sure helped my spirits a lot.”

Someone asked how much Intersport had paid God for the change in the weather, and Bob Hicks replied that he thought they’d fooled him up there. “The Berkshire is always a two-day event, so he made rain on the second day, then it cleared up.”

Dave Eames had gotten a chance to talk to his father on Saturday night, and was warned that there would be no time to breathe after the third check. Sunday’s route included a 17-mile stretch known as “Sucker Pond.” Tom Penton “didn’t think very much of that....” Seventeen miles of continuous mud. Yet Bill Uhl arrived at the next check 12 minutes early. Are you ready for that?

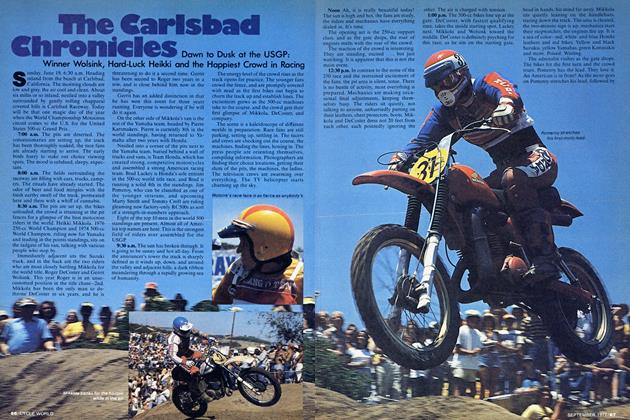

At Sunday’s timed hillclimb, AÍ Eames made one of the few PR mistakes of his career. He’s used this spot before, and had permission for the bikes to run on the land. But he hadn’t anticipated the number of spectators who would show up.

They arrived in droves; the early arrivals didn’t park too carefully, the later ones couldn’t get in to park, so they parked on the property of a local farmer whom AÍ had not approached. He had also neglected to call the Vermont State Police. The farmer, however, did not neglect to call them, and they showed up to find out what was going on. The officer involved was mostly embarrassed that he couldn’t answer the farmer’s questions. AÍ heard through the grapevine that had he asked the owner’s permission, there would have been no problem, and since no damage was done, apologies were all that was in order.

Shortly after the hillclimb a band of “outlaw types” was spotted riding their choppers through Williamstown, Mass., with a police escort. This isn’t the type of event to draw such a crowd, so it probably was an unrelated incident, but gas crews on hand by the side of the road got a chuckle from it anyway.

There were few injuries this year. Photographer Boyd Reynolds was riding a 250cc Honda and was forced off the road at one point by a car. He avoided injury, but two other riders at the same point went off to the hospital with minor broken bones.

Probably the most serious injury was to Ray Boasman, a popular Canadian, who had caught a tree branch right behind the eye, and couldn’t see out of that eye. He would have to visit an eye specialist as soon as he got home to determine if the loss of vision was permanent. He was in a fair amount of pain, and the doctors had given him medication only for use to help him go to sleep.

Sunday afternoon, after the efficient checkers had done their job, the crowd gathered outside for the awards ceremony.

The medals had to be individually engraved with the rider’s name, so the winners got only a certificate. Team trophies were awarded at this time, however. Bob Hicks received a special trophy for his part in laying out the run, and preparing the literature for the event—the best job yet in that respect, with a three-color map showing the different days trails. And Mike Vancil heaped praise on Al Eames:

“Through your efforts—and perhaps 90 percent through your efforts, the riders in this country are getting better, and better, and better, and better....”

And when it was all over, a Yankee Motors employee asked boss John Taylor “What would be the best time to come to work tomorrow?

“Oh, ten o’clock,” replied the efficient Mr. Taylor, thinking he had made a grand concession. When he saw the look of dismay in the petitioner’s eyes, he quickly added “...or later.” It had been that kind of a weekend.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue