LAFFERTY

K. P. Boyte

HAD THERE BEEN a crowd, they'd have cheered as Lafferty rode by. As it was, there was only me; and, while I admired his mastery of the big machine, I could not applaud a man I'd come almost to despise.

Lafferty belonged in front of a crowd, tearing up a dirt oval and leaving the rest behind. He was obviously a pro, he had all the skill and daring required, but he also had a ruthlessness that put him beyond fair competition. Perhaps that’s why I sat watching him here in the desolation of the Mojave desert instead of on the track at Ascot.

I watched him round the turns, cutting close, giving little, then break onto the straightaway roaring full out. He was magnificent, he was in his domain. I could accept it all with the grains of sand at my feet, yet one thing kept it all from being real. Lafferty belonged to the past. It was like watching a page in a motorcycle history book come alive and run circles around me. It was uncanny and eerie and just on the edge of unbelievable, yet there he was racing past me once again, denying the fact that it was 1972, denying the fact that it was any time at all.

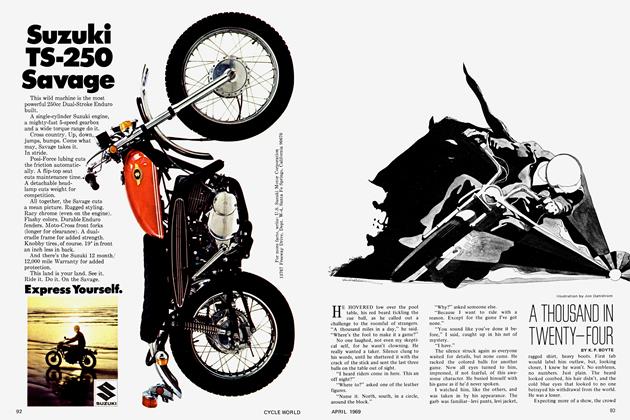

The bike was a Brough Superior with a 976cc J.A.P. engine, vintage 1923, and Lafferty’s vintage was about the same. Dressed in the garb I still found difficult to accept, even in the history books, he was as far from today as you could get: jodhpurs tucked into high laced boots, white sweater covering white shirt and tie, goggles and a thin half-shell helmet. What do you call someone like that? Nut? Kook? Those fit right up until the time he climbs on that machine and shows you how its done in the big time. Then words fall against a rock wall of skill; then you remain quiet and watch the man do it all.

That’s what I’d found myself doing since my first day on Lafferty’s premises-remaining quiet and watching. I was free to join him on the track—I’d arrived here specifically for that purpose—but until I acquired some degree of skill, I would remain spectator until he was done for the day.

An ad in CYCLE WORLD had drawn me here from the comfortable confines of unemployment—an ad that, once read, gnawed until I rolled the sleeping bag and headed out.

“Ride with old pro. Time and motorcycle only requirements. Lafferty. 6-mi. N. of Boron. Road marked.”

Simple and inviting, especially to one who possessed exactly the requirements he specified and not much more. I had arrived unheralded and remained in virtually the same state for 10 days. Motorcycle companion might well have been my title, yet Lafferty seemed far from needing a companion. He spoke only when prodded and then his tone was brusque and harsh with a distinct don’t-bother-me air. I always wanted to remind him that I was asked here by the ad but it never seemed to be appropriate.

He had instructed me, after much prodding on my part, on track skills and even invited me to join him thereon on several occasions. 1 don’t know if it was my lack of skill or the gleam in his eye that kept me away, but I was content to work alone when he was gone, perfecting my own riding abilities until one day, when skill was something I solidly possessed, I would join him and beat him.

Now, sitting atop the hill that was a natural grandstand, I watched his unceasing domination of the dirt oval he himself had carved into the desert floor. He could go for hours and today was no exception, so I watched patiently, waiting for the time when the track could be mine. Again and again he passed by, then suddenly he stopped at the foot of my spectators hill. Without words he threw up a challenge. Raising his goggles and staring directly at me, he needed nothing but penetrating silence. Our eyes locked for close to a minute, then a grin broke slowly across his face as he began to shake his head. He was calling my hand. He had allowed me 10 days to learn, now he wanted the race.

I didn’t move and he lowered his goggles, started his motorcycle and resumed his place on the track. The choice was mine and I considered it carefully. I didn’t want to go out there and lose, yet I didn’t want to grant him the satisfaction of bluffing me out of competition. I recalled the grin, the defiant, daring grin set in his stone cold face, and I got up and went to my motorcycle.

He had me in overall power but I had him in weight. My Kawasaki looked about half his Brough and I reassured myself that this factor might make up for some of the skill I lacked. That was all I could find on my side as I kicked my machine to life. Determination would have to make up for the rest.' I let him go by, then sped out onto the track, gathering speed and courage with each second. I was nearing the turn when he roared past, cutting in front so closely that I nearly lost it all. Lafferty didn’t ride—he charged, like an angered bull, and beware those who got in his way. I made the turn, somewhat slowed, then gained speed once again. I knew he’d come past again, but this time I held ground, eased just slightly, and poured it on as I came out of the turn. Conditioning my mind wasn’t easy, but necessity won out. If I was going to stay out there I’d have to all but shut him out.

He was lapping me and loving it, I supposed, so I picked up speed and held my ground. He might win the race but he wasn’t going to run it all. We headed into a turn, I was in the lead, he was roaring up from behind. I held it tight, he tried for the inside and, clenching my teeth, I still held. I wasn’t going to give. He wasn’t either, I found, and he came alongside, his wheels off the inside track. We broke from the turn together, but he veered sharply toward me and caught my wheel with his. From there it was sliding, grinding, scorching, then muffled sounds of dying machines. Both still running, they lay ahead on their sides while Lafferty and I sprawled a little ways behind. I felt the pain of flesh scraped raw but nothing worse, so I got to my feet and walked toward the motorcycles. Lafferty stood also, brushing dirt from his pants and sweater, all the while glaring at me. Astride my undamaged motorcycle, I sat watching his slow burn. I could see the anger building; he had removed his goggles and the creased brow and tightened jaw tensed as seconds passed.

He was halfway to me when the tirade began. It was more words than I’d heard the whole 10 days.

“Man goes out on the track looking for a good clean race and all he finds is dirty punks who don’t know what fair competition means! Good hard ride, good hard race, nobody can take it! Nobody wants it! Just tear it down! Going good, then just tear it down!”

He was nearly shouting but it didn’t seem to be at me. The fire in his eyes was fierce, his rage was frightening and he kicked dirt, paced about, even kicked the motorcycle as he vented every shred of his anger. I wanted to ask, but I could see he wasn’t to be interrupted. It didn’t fit and I wanted to know why. He wasn’t mad at me, he was mad at the whole world.

He righted his motorcycle and rode away, out across the desert, his words streaming behind. Once again Lafferty was gone. Once again I was alone, but this time I was left with more of the man than ever before. There was something inside him eating away at his soul, possessing his every minute of life, turning him against the world. Whatever it was, it was responsible for the lack of communication for 10 days and now that there was a reason, whatever it might be, I didn’t despise him quite as before. I doubted I’d ever like the man; but now, somehow, I could tolerate him.

I rode back to the cabin that was home for the present. It was Lafferty’s but he seldom ventured inside. He had shown it to me on the first day and had not been near it since. Where he slept, where he took his meals, where he spent the hours away from the track I never knew. I only saw him racing, that seemed to be all the life he had.

There was always food, however. Somehow, unseen, he managed to keep the cupboard full, so life with Lafferty, while mysterious and sometimes a bit edgy, was nevertheless comfortable. Bed and board were enough to make me stay.

The cabin was crude, unpainted, one room. It had a minimum of furniture and not the slightest hint of decor nor even a trace of anything that spelled Lafferty. No clothing, personal items, nothing. At first it bothered me but when I found I couldn’t add it up, I quit trying. It was a pleasant enough life, a trifle off-beat, but better than the nothing I’d had before.

I made a sandwich, scrubbed off some of my dirt, and relaxed awhile, all the time my mind stuck on Lafferty. In the 10 days past, I had come to accept him for whatever he was and let it go at that; but after this outburst, my interest flared and the mystery again was new.

There was so much that didn’t fit. His appearance, his motorcycle. Why? He was too young to be real—he looked to be in his mid-40s—and that was far too young to be a 1920s racer. So he wasn’t real, then why did he stick with that era? What was it? I’d heard of antique buffs but he was a little much. And the machine. A miracle to be running so hard in its 48th year. How possible? Where do you get parts for a Brough Superior? All the questions raced around, there was no way to organize the inquiry. Always I wondered the same, always I answered the same. Possibly he was perpetuating the memory of a father or uncle or just a hero he admired. But why out here in the middle of nowhere? In a second I answered that one: how would he appear in the middle of contemporary society?

Sandwich and relaxation finished, I went back to the track, surprised not to find Lafferty there. He seldom wasted many daylight hours away from the oval, but perhaps the morning’s incident had dampened his spirit. Looking out across the desolation surrounding, I wondered where he really lived. Was there another cabin out there or maybe a cave? I thought of searching but nixed that. He wanted privacy, I’d interfered enough.

Alone, moving at my own speed, I worked to perfect skill and style, to make it second nature to take the turns, to open up wider on the straight stretches, to make the track faster and faster. I covered the ground again and again, each time demanding more of myself and my machine until I felt confidence growing. I started to see how Lafferty could do it all so well. If you knew the track, knew all the feelings possible, knew how to handle the motorcycle’s every move, then you were unbeatable. I could feel it happening and I realized the time would come when I would pass Lafferty by, when he would take the defeat he so richly deserved.

It seemed hours before I ceded to fatigue and left the track. Calling it a day wasn’t the giving up that usually set the time limits. Today it was a genuine sense of accomplishment. Reveling in my own strides of progress, I almost failed to notice Lafferty, who had returned and sat atop the grandstand hill astride his stilled motorcycle, watching.

I rode to the base of the hill and waited for him to come down. He stalled, avoiding confrontations as always, then realized I wasn’t giving and came down. He stopped beside me and waited. Seizing the opportunity, I asked away.

“Where did you get your motorcycle, Mr. Lafferty?”

I’d asked it before and never gotten a reply so I didn’t expect one now. I assumed right.

“Was it your father’s? Or a friend’s? Or did you just buy it and restore it?”

His harsh expression softened and he seemed to be searching for an answer inside. He found none and remained silent.

“Why do you wear rider’s clothes out of the ’20s?”

He shook his head and we silently agreed answers were futile. He wasn’t going to answer so I should give up the inquiry. I smiled, shrugged and he, without a smile, passed a look that seemed almost apologetic. He couldn’t tell me. He couldn’t.

He went out on the track and did his time. I left him alone, as I knew he wanted to be now. I watched the same sight I’d watched for 10 days and I wondered the same questions over and over as I had for 10 days. Something of the past was too precious, too fragile, too important to reveal. Whatever it was, he would never tell, yet I was> determined to know. He had caught me up in his mystery, he had asked me here to ride with him, and I would find out why before I left.

The night was long, as usual I didn’t see Lafferty. My mind had him close, though, it wouldn’t let go. Over and again I questioned, until finally one bit of probable information surfaced. A friend back in Los Angeles, his uncle was a motorcycle history fanatic, had all kinds of books on old bikes and racers, everything. Maybe he could find a Lafferty. In the morning I’d ride into Boron and make a call.

A telephone in the drugstore in Boron took me back to reality for awhile and the trip felt good. My friend took the inquiry and promised to call back as soon as possible. Meanwhile I waited alternately at the magazine stand and soda fountain. An hour had passed and hope was thinning under the pressure of impatience, when the phone rang and the information was at hand.

William Lafferty raced in England in 1923 and ’24, was a top name at Brooklands and Clipstone until disqualified from a 1st place finish at Brooklands in 1924. He then came to the United States, where he found little success and was finally killed on the track in 1928. He was age 45 at his death. He had a son, Charles, who was his mechanic throughout his racing career.

I thanked my source several times and hung up the phone. It all fit together now. Charles Lafferty was here in the Mojave desert reliving his father’s career as a racer, even down to the bitterness his father must have felt at the disqualification at Brooklands. Yes, it all fit together, very neatly, and the final logic was that under the circumstances, Charles Lafferty was a nut. As ruthless as he was on the track and as mysterious as he was off the track, I wondered if it was really worth the return. He could do nicely without me.

Outside the drugstore I pondered direction. I had a yen to go back to Los Angeles—the phone call, outside contact, beckoned home—yet Lafferty was still out there and I would still like to beat him on his track. With the mystery gone, some of the lure of adventure was gone, too; still, now with firm ground to stand on, I could concentrate on that final race I knew was imminent. I headed back to Lafferty’s road.

The morning sun had now moved high overhead and it warmed my back as I traveled Lafferty’s road. Churning dirt and sand, chunking along over rocks and brambles, I mused at this even being considered a road. It lost the battle for existence entirely every time a dry wash came along, then it picked up its feeble path and pointed the way ahead. That seemed to be all it really did, point the way ahead, and I wondered if Lafferty ever went to town.

I found him on the track, as expected, and sat watching for a few minutes, determining if the challenge was to be now. The strange mixture of admiration and displeasure that had marked my attitude toward him thus far was now gone. I felt only a kind of pity that such a skill should be destined to fill its years with nothing more than desert sand. He was no longer the elusive rebel, the mysterious soul dedicated to his own peculiarities. He was now simply a sad case; a sad case with skill, however.

Viewing Lafferty in a different light bolstered my confidence and when I asked myself the final question—could I beat him—that confidence answered back quickly to the affirmative. I joined him on the track.

He passed me immediately, before I had gathered any speed at all, and I vowed that was to be the last time. It was my turn now. Everything I had learned, everything I had acquired in the way of skill and knowledge was called to the front as I challenged him. Riding his tail, I held close, following him through the turns, unrelenting, then clinging still as he opened up and tried his best to lose me. I had him now, there was no letting up.

One final challenge left, the biggest one of all—passing him—and I waited. Lap after lap we moved in unison, so closely that I found my mind wandering to his, wondering at his thoughts, wondering if he wavered at all in his confidence. He never looked back, nor to the side; he remained fixed, front runner giving no ground. It was that unceasing look ahead, that lack of concern for my presence whatsoever that drove me to the final move. Coming out of a turn I opened up, cutting wide on the outside bringing my machine alongside his. I pulled inches ahead and still he was unconcerned. I could feel that much and as he suddenly hit the turn I saw why. I eased off and he took the lead, rounding the turn, then back out onto the straight strip that said go. Again I made the move and again I lost it in the turn. He knew I wouldn’t make it and it showed. He just kept his normal pace and let me run around the edge.

Recalling our episode the previous day, I knew my only chance was the inside but I also knew the price I would pay if he didn’t give. How could I squeeze past if he didn’t give? Through one more turn trailing, then gathering nerve for the move, then again into the turn but this time on the inside, pushing, inching. It was frighteningly close, my front tire nearly grazing his back as I claimed the tiny strip of track he left on the inside. It wasn’t enough, though, and I felt my machine slipping from the dirt so I eased off and fell behind once again. One more try I told myself. Only one more, so make it work.

Taking the inside again I pulled up toward him, stealing ground, making him give. I pushed ahead, my motorcycle screaming with the strain, and as he gave way to my determination I caught the turn of his head with the corner of my eye. He slipped behind for a second then suddenly veered off to the right, off the track and toward the grandstand hill. I lost sight as I met the turn, then eased my machine and cut back across to see what had happened. The Brough was lying at the bottom of the hill, a deep gouge carved by its downward slide, but Lafferty was gone. I dropped my bike and ran up the hill but he wasn’t there. He wasn’t anywhere. I expected to see him running off across the desert, running to his sanctuary to hide the shame of defeat, but I couldn’t find him. Could he have possibly run so fast as to be out of sight by the time I reached the hill?

I stopped my search, pulled off my helmet and rubbed my eyes. I had won but, damn, he had somehow stolen the victory from me. I sat down, then lay down, on the hill and let the dust inside settle. I had beaten him and he had disappeared. Now what? Another mystery? No. No more. Lafferty could remain out here forever, I could not and would not. He belonged out here away from the world, left alone with his fantasies. I was glad to oblige.

I went back to the cabin to pick up my sleeping bag, still feeling cheated although I reminded myself I had won. I had passed him and had he not veered off the track I would have remained in the lead. I knew it. It was fact, yet why then was there not the satisfaction I had anticipated? That was Lafferty's fault. He stole away and took with him all the glory of victory. He never gave me a chance to feel that victory for more than a second. He couldn't allow me any more than that second. I recalled his tirade about fair competition and wondered just what it was he considered fair.

(Continued on page 127)

Continued from page 88

Outside and packed to leave I looked around at the desolate ground that had become a maze of fantasy for me. Lafferty was out there somewhere and I should have been content to leave him out there, but something drew me to one final look around. I started my motorcycle and made a wide ioop out past the track, all along the foot of the nearby hills, then back around behind the cabin. I found not a trace of Lafferty. I chided myself for this need to confront him verbally with my vic tory, then patted my bike and said "Let's go home." Pulling up near the cabin's backside, I turned to circle out to the road, but stopped short as some thing caught my eye. Funny I hadn't noticed before, but I guess I'd never really concerned myself with what was behind the cabin-desert everywhere is easy to assume. Now something called me to it and I parked my bike and walked to see. There, tucked neatly behind the cabin, shaded and hidden by its presence, was a grave neatly bordered with stones and headed by a crude wooden marker. I don't know what I expected but the words I found sent a chill from my neck down to the base of my spine. Charles Lafferty. 1903-1972. Before my eyes everything unraveled. Reality fell apart as mystery and un certainty claimed their victory.

I tried mental calculations with years, but nothing worked. Alive or dead, Charles Lafferty's age didn't match with the man on the track and if Charles was in the ground, who had done all the riding? There was only one left but years and vital statistics were beyond comprehension. William Lafferty was an impossibility.

"No way," I said aloud as if that might help the denial. "No way!"

Shaking my head, feeling my insides shaking too, I hopped on my bike and found the road fast. Out was the only answer, but a few yards away I stopped and turned for a final look, hoping, even half expecting the house, the hill, the track, the whole unbelievable scene, not to be there. It was, however, and for all I knew, Lafferty was too. E~1