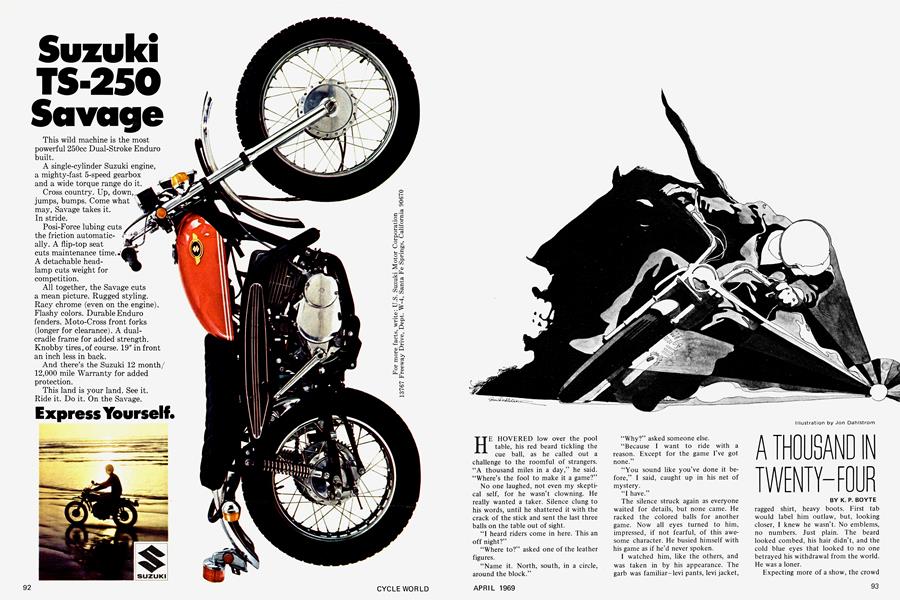

A THOUSAND IN TWENTY-FOUR

K. P. BOYTE

HE HOVERED low over the pool table, his red beard tickling the cue ball, as he called out a challenge to the roomful of strangers. “A thousand miles in a day,” he said. “Where’s the fool to make it a game?” No one laughed, not even my skeptical self, for he wasn’t clowning. He really wanted a taker. Silence clung to his words, until he shattered it with the crack of the stick and sent the last three balls on the table out of sight.

“I heard riders come in here. This an off night?”

“Where to?” asked one of the leather figures.

“Name it. North, south, in a circle, around the block.”

“Why?” asked someone else.

“Because I want to ride with a reason. Except for the game I’ve got none.”

“You sound like you’ve done it before,” I said, caught up in his net of mystery.

“I have.”

The silence struck again as everyone waited for details, but none came. He racked the colored balls for another game. Now all eyes turned to him, impressed, if not fearful, of this awesome character. He busied himself with his game as if he’d never spoken.

I watched him, like the others, and was taken in by his appearance. The garb was familiar-levi pants, levi jacket, ragged shirt, heavy boots. First tab would label him outlaw, but, looking closer, I knew he wasn’t. No emblems, no numbers. Just plain. The beard looked combed, his hair didn’t, and the cold blue eyes that looked to no one betrayed his withdrawal from the world. He was a loner.

Expecting more of a show, the crowd endured the silence, but as minutes passed they lost interest and turned to themselves. The lull of voices mixed with music and returned the room to normal. I had no plans, so I waited until he finished his game, then offered to buy him a beer.

IN A CIRCLE, AROUND THE BLOCK...THE CHALLENGE WAS DISTANCE, TIME... AND REDBEARD...

“Thinking about that thousand?” he said, his words striking like a prophecy.

“Just thinking,” I answered.

“That’s enough for a beer.”

He stood beside me at the bar and waited for my questions.

“You’re willing to bet me you can ride a thousand miles in a day and I can’t?”

He nodded. “You’ll come in second.”

“How much of a bet?”

He looked at me, and though I was dressed far better than he, he said, as if for my sake, “Another beer.”

Any çhallenge is hard to turn down, for the chance to prove oneself is golden, but with vacation time on my hands and no definite plans made, this man’s game was gilded beyond reason. I held out my hand; he shook it with finality.

“Meet me here tomorrow night,” he said. “Tell me the route and time. Any way you want.”

Left alone in the crowd I felt lost, the weight of the newfound challenge resting heavily on my mind. A thousand miles in twenty-four hours. I had no idea if I could do it, let alone beat his time. My stomach tightened and I knew it wouldn’t let go till the game had ended.

Late into the night 1 stared at the map of California. Because of the desert to the east, I decided to stay in my home state, but it still was big and a thousand miles fit many ways. Might as well see as much as possible, I reasoned. Start with familiar territory, then hit the unknown.

After hours of deliberation I settled on a route—a large triangle that measured roughly 1000 or 1100 miles. What’s an extra hundred now that I’m committed to extremes? Up the eastern side of the state from Los Angeles, west across its width to San Francisco, then south on coastal Highway 1 to Los Angeles. Might make someone a nice threeor four-day trip. I traced the route in red on the map, then set about the timing. Getting the night riding done first sounded practical, but that would take me through mountains and unfamiliar territory in the dark, so I decided on midnight for departure. That would start me in darkness, yet bring on light when needed, then let night fall as I headed back into home territory. All

set. Now when? I could sleep a whole day beforehand, but with nerves knotting fast the sleep would be a waste. If he was willing we’d leave the next night.

He was at the pool table when I walked in, and before I was well settled he was at my side. “Midnight tonight,” I said. A smile and a nod agreed. We traced the route on the map, his nodding head taking it in. Then the smile again. “From here?” he asked.

“Fine.”

With my fate now set, and two hours till midnight, I was all the way nervous. “Red Beard” went back to the pool table, I sought the night air. At a time when I could be resting all the parts of me that would soon need resting, I rode. Nothing else was enough. If I sat and thought I might question myself, and things were past that now.

At eleven I went home to pack. Pack? Not much. Just money, my jacket on my back, helmet, and shades. I checked my machine over carefully, realizing that I could use a new rear tire and a few other things. Too late, though, so I added oil, tightened the drive chain, and went for gas. Midnight came close.

Going back to meet my opponent, I realized, on seeing the line of bikes parked at the curb, that I had no idea which was his. Was it the noiseless touring bike, the full-dress giant beside it, or one of the 650s like mine? Or was it the chopper at the end of the line? That one looked like him. As I parked beside it I caught sight of the red beard coming toward me. “What time is it?” he asked.

“Ten minutes till,” I answered.

He mounted the chopper, settling onto the small seat it wore, and I applauded silently my accuracy. I must have glowed, for he looked through me, unsmiling, and said, “No doubt.”

Caught in the awkwardness of the moment, I was at a loss for the conversation that usually flows between riders.

To this man my words didn’t belong-I felt anything I said wouldn’t reach. My watch provided diversion and as the hands narrowed into one, I said, “Let’s go.”

A few kicks, a lot of noise, and then it began. Down a main street empty from weeknight rigidity we rode toward the freeway, side by side, yet miles apart. A mismatched pair if ever. Sidelong glances in his direction told a story.

A man set apart, by choice, maybe by need—alone, yet so sure astride his machine. I looked closer, finding his bike not the radical chopper, but more the basic-no upsweeps, no sissy bar, painted a glossy black. It was clean and

sounded perfect. Undoubtedly it was dependable.

Suddenly he veered away from me and I jumped to conclusions of trickery, but his path was into a gas station. I slowed to watch, not thinking of the gain I could take, and saw that he was just getting gas and cigarettes. Evidently he hadn’t taken time earlier to tend to details. Dumbfounded by this casual treatment, I turned on more power and found the freeway fast. Down the ramp and into the center lane I left him far behind, my speed christening the start of the race. Not until I reached San Francisco did I begin to doubt him.

From the gas station in Los Angeles I rode alone, and not once again did I catch sight of the chopper and the red-bearded rider. Out of darkness into a scorching morning on the desert, then turning east on the triangle’s second side and climbing into the green cold of the mountains of Yosemite National Park. Stops were short-for gas, a breather, maybe a sandwich and coffee, but at the summit of Tioga Pass, where snow-covered mountain tops just above flaunted the fact that it was late June, I stopped to give my machine a breather, too. Struggling like a chain smoker, it coughed and hacked in the thin air until I could force it no more. Beside one of the glassy lakes I rested it and wondered at the remedy for high altitude carburetor failure. Checking my map, I found that from here on it was one giant, downhill ride, so I decided to alter nothing. I pondered, then, on the whereabouts of the competition. He had to make twice as many gas stops, so I could very likely stay ahead the entire race, yet, with all the confidence he had displayed earlier, I expected him to stay with me at the least. Out of curiosity I rested nearly half an hour, but when still he wasn’t in sight I mounted and rode, hoping now I hadn’t given him a chance at catching me.

The ride from then on was one I vowed to repeat sometime when there was more time. Winding downhill it went too fast, past more lakes than I’d ever seen, with fishermen and campers taking advantage, and the smell of open cooking drifting across the road too often. Traffic there wasn’t. I was alone on a mountain ride, chilling air slapping my face, routing all the Los Angeles smog from my lungs. Then Yosemite ended and the highway that led toward San Francisco turned into an unlined, one-lane ribbon that wound and curled for seven miles. Speed through here was unthinkable, so I enjoyed the tight turns that never once broke into a straight stretch. After that I left all shades of green behind and entered “golden” California. The heat came with it, drawing the skin on my face tight, burning it, baking me through. Still descending, still winding, down golden hills of useless golden foot-high grass, through tiny towns perched on hillsides with streets that made even a motorcyclist feel wide. One called Groveland struck my fancy, so I stopped.

It wasn’t much, but had that small, slow quality that city folk have no idea exists until they discover it unintentionally. I had a Coke in the town restaurant—an adobe building fronted by wooden sidewalks, right out of yesteryear. People were friendly, and from the waitress I heard an unsolicited history of the town and how it was a historical landmark in its entirety because Mark Twain had once lived there. Interesting, but time consuming, so I stepped up my pace and left Groveland behind.

From there to San Francisco, monotony was the word, for the gold hills that made the heat seem even greater kept on and on, stretching, rolling, never ending. Highway turned into freeway and traffic increased as San Francisco neared. Exhaustion already sat heavy on my back and I wondered how my motorcycle felt. We were roughly halfway, I was beginning to ache, but my machine just kept on. Outside of the cough at Tioga Pass, it was unaffected by the long miles. It seemed instead to thrive on this long trip. I wished I could say the same for myself.

I could feel Oakland before I could see it. The smell of the sea and the coastal wind crept out of the bay and back into the hills for a few miles. The chill was welcome, and I rode on through Oakland and across the Bay Bridge in my shirtsleeves. San Francisco’s fog was out of town that day, and the city was open for a spectacular view. I wound up and down its hills, hanging on a burning clutch at many a hilltop stopsign, then feeling my stomach drop as I sped downward. I wasted some time here, too, riding down to Fisherman’s wharf and having a lunch of shrimp and chips at an outdoor stand. So involved was I in the world immediate, that I hadn’t given much thought to the race that had brought me here, but as I sat eating the hot shrimp, that first finger of doubt crept across my mind.

I hadn’t seen him leave. What if he was still in Los Angeles. What if Red Beard was right now amusing his friends with tales of a guy riding 1100 miles for nothing? What if I was the butt of the biggest joke ever? The supposition solidified into a tormenting doubt. It would have been easy. He just let me get on the freeway while he sat in that gas station, then he went back to play some more pool. I had really fallen.

I left the shrimp and the wharf and rode aimlessly for awhile. The reason was gone. I was in San Francisco for nothing. No amount of self-consolation would help. I though of staying, making a vacation out of it, but no, that would be giving up. Suppose I was wrong? Suppose I was just sporting a good lead—too good almost for the doubt it created. I had to finish. Whether to find him there, laughing, at the finish, or to come in ahead, I had to do it. If for nothing more than the challenge that had sounded so wild in the beginning, if for nothing more than to prove to myself that it could be done, I would finish in twenty-four.

It was already afternoon when I left San Francisco, but with steady riding I could easily be in Los Angeles by midnight. Highway 1 wound a lot; 101 would have been much faster and for a time I even considered taking it. If the competition could cheat...

Conscience, however, set me on Highway 1 in the middle of the fog that belonged in San Francisco. It stayed with me clear to San Simeon and kept my face damp along with my spirits. This highway was new to me. I’d been told often how scenic it was, but all the views in the world could have been lost in the gray mist. A fire-breathing dragon could have chewed up the beach and I wouldn’t have noticed.

Monterey, Big Sur, San Simeon, then dawn in the fading afternoon. A glimpse of the fast setting sun was all the lifting fog revealed, and night brought me into San Luis Obispo. Not many miles left, nor much strength. I was tired to the core. Aching back, cramped hands, stiffening neck. Shifting gears even seemed to take extra effort. The bike seemed tired now, too. Still going great, it felt almost too loose, as though it had unwound too far, been driven too hard. We were both due for a long rest, but not until Los Angeles.

I joined Highway 101 as I left San Luis Obispo, but my conscience was clear for this was the appointed route. It was all speed from here on. The closer I got to Los Angeles, the more uncertain I grew about the race. Maybe I was just tired and my suspicions were a product of fatigue. Maybe I’d be there first and stand quietly as he pulled in behind. Maybe I’d be there first and win that beer after all.

Santa Barbara, Ventura, Oxnard, closer and closer. Then Los Angeles, then off the freeway, then down the street to the finish. Whatever part of me that still was awake and going began to tense in anticipation. My stomach knotted, my throat dried out. A final turn, a couple of blocks, a finish.

Avoiding that long searching look down the row of bikes at the curb, I stopped at their end and shut off the engine that had been my only friend. It was done. I checked my watch. It was eleven-ten. For all the good it did, I gave myself a mental pat on the back. Then I turned to see who was the victor.

The row was a mass of handlebars, seats, and chrome that seemed to dance in the streetlight’s bright shafts. They all meshed together, too much, too many. I was tired enough to almost not care, but the last bit of energy inside pulled me off my machine and sent me down the row looking. I walked slowly, glancing down at each bike, not glad to call them unfamiliar, not sad when I found the one.

Dust covered, engine still warm to the touch, pipes still hot enough to singe inquiring flesh, it sat emitting all the creaking, settling sounds that hail the end of a hard ride. Based on the machine at my feet I had lost, but doubt flickered again and gave me reason for a little more hope. He could have ridden for three or four hours and done the same thing. Time traveled and miles covered weren’t recorded in the dirt and dying sounds of a stilled motorcycle. I went inside to finish the finish.

He was at the pool table as though it all never had happened. For all the change there was, I could have been lost somewhere between midnight and a 13th hour. I sat waiting while he finished his game, then he came and sat beside me. From the look on his face I knew he could read me through, but he waited for me to speak first.

“What time did you get in?” I asked.

“Ten-thirty,” he answered.

If I was ever to challenge his authenticity, now was the time, but the words wouldn’t go together and the challenge didn’t fit. He saw the questioning, perhaps felt the doubt. From inside his shirt pocket he pulled a folded card, a postcard. He offered it silently.

Painted on that small cardboard rectangle was the picture of that small place that had left, evidently, a lasting impression on him as well as me—Groveland. I smiled, not so much conceding defeat as shedding the doubt.

“Buy you a beer,” I said, and he smiled and scratched his beard and nodded.