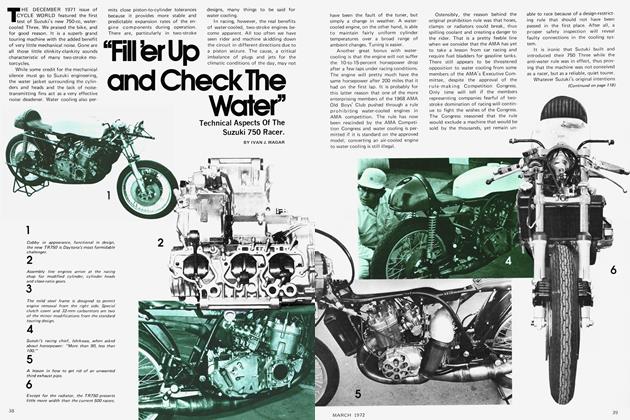

Riding The TR750

Our Assistant Editor Dons His Factory Hat.

JODY NICHOLAS

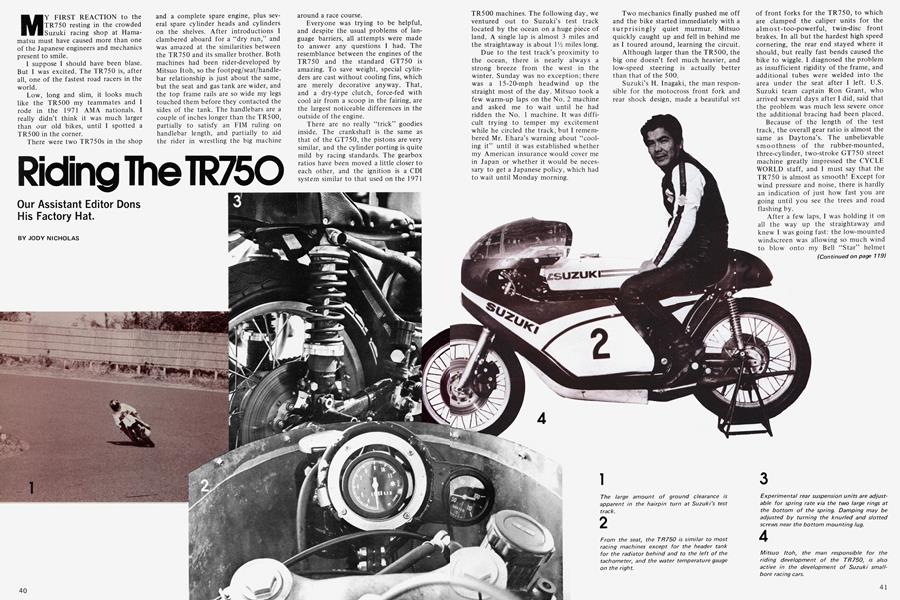

MY FIRST REACTION to the TR750 resting in the crowded Suzuki racing shop at Hamamatsu must have caused more than one of the Japanese engineers and mechanics present to smile.

I suppose I should have been blase. But I was excited. The TR750 is, after all, one of the fastest road racers in the world.

Low, long and slim, it looks much like the TR500 my teammates and I rode in the 1971 AMA nationals. I really didn’t think it was much larger than our old bikes, until I spotted a TR500 in the corner.

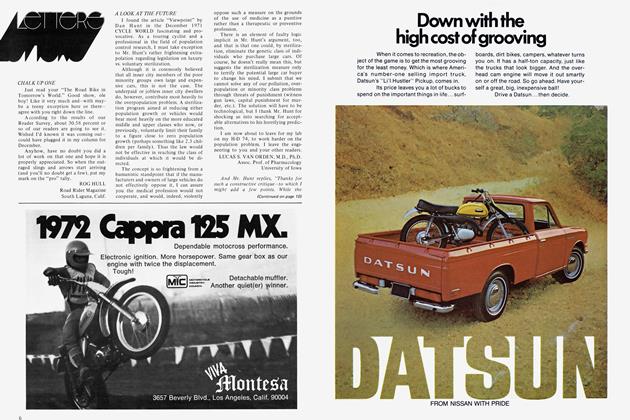

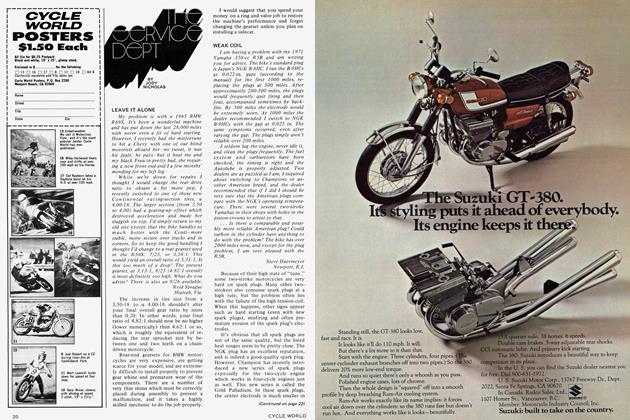

There were two TR750s in the shop and a complete spare engine, plus sev eral spare cylinder heads and cylinders on the shelves. After introductions I clambered aboard for a "dry run," and was amazed at the similarities between the TR750 and its smaller brother. Both machines had been rider-developed by Mitsuo Itoh, so the footpeg/seat/handle bar relationship is just about the same, but the seat and gas tank are wider, and the top frame rails are so wide my legs touched them before they contacted the sides of the tank. The handlebars are a couple of inches longer than the TR500, partially to satisfy an FIM ruling on handlebar length, and partially to aid the rider in wrestling the big machine around a race course.

Everyone was trying to be helpful, and despite the usual problems of language barriers, all attempts were made to answer any questions I had. The resemblance between the engines of the TR750 and the standard GT750 is amazing. To save weight, special cylinders are cast without cooling fins, which are merely decorative anyway. That, and a dry-type clutch, force-fed with cool air from a scoop in the fairing, are the largest noticeable differences in the outside of the engine.

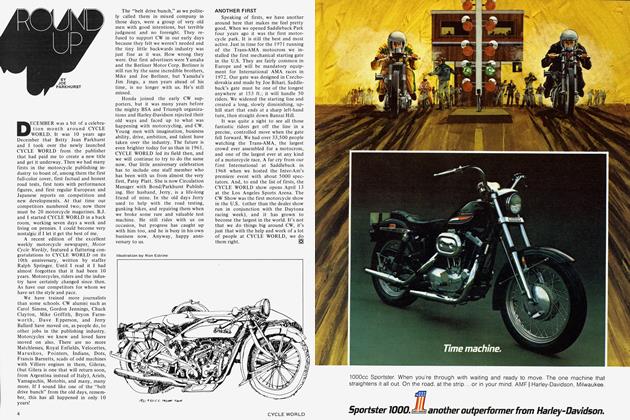

There are no really “trick” goodies inside. The crankshaft is the same as that of the GT750, the pistons are very similar, and the cylinder porting is quite mild by racing standards. The gearbox ratios have been moved a little closer to each other, and the ignition is a CDI system similar to that used on the 1971 TR500 machines. The following day, we ventured out to Suzuki's test track located by the ocean on a huge iece of land. A single lap is almost 3 miles and the straightaway is about 1½ miles long.

Due to the test track's proximity to the ocean, there is nearly always a strong breeze from the west in the winter. Sunday was no exception; there was a 15-20-mph headwind up the straight most of the day. Mitsuo took a few warm-up laps on the No. 2 machine and asked me to wait until he had ridden the No. 1 machine. It was diffi cult trying to temper my excitement while he circled the track, but I remem bered Mr. Ehara's warning about "cool ing it" until it was established whether my American insurance would cover me in Japan or whether it would be neces sary to get a Japanese policy, which had to wait until Monday morning. Two mechanics finally pushed me off and the bike started immediately with a surprisingly quiet murmur. Mitsuo quickly caught up and fell in behind me as I toured around, learning the circuit.

Although larger than the TR500, the big one doesn't feel much heavier, and low-speed steering is actually better than that of the 500.

Suzuki's H. Inagaki, the man respon sible for the motocross front fork and rear shock design, made a beautiful set

of front forks for the TR750, to which are clamped the caliper units for the aim o St - too-powerful, twin-disc front brakes. In all but the hardest high speed cornering, the rear end stayed where it should, but really fast bends caused the bike to wiggle. I diagnosed the problem as insufficient rigidity of the frame, and additional tubes were welded into the area under the seat after I left. U.S. Suzuki team captain Ron Grant, who arrived several days after I did, said that the problem was much less severe once the additional bracing had been placed. Because of the length of the test track, the overall gear ratio is almost the same as Daytona's. The unbelievable smoothness of the rubber-mounted, three-cylinder, two-stroke GT750 street machine greatly impressed the CYCLE WORLD staff, and I must say that the TR750 is almost as smooth! Except for wind pressure and noise, there is hardly an indication of just how fast you are going until you see the trees and road flashing by.

After a few laps, I was holding it on all the way up the straightaway and knew I was going fast: the low-mounted windscreen was allowing so much wind to blow onto my Bell "Star" helmet that I thought it, and my head, would be jerked right off my shoulders! When I pulled back into the pits, they told me that there was a really strong headwind and that I had only turned 262 kph, which is roughly equivalent to 163 mph!

(Continued on page 119)

Continued from page 41

Several laps later I was beginning to get the hang of the bike and started making pretty good time around the test circuit, in spite of Mr. Ehara’s warning. The braking is fantastic: no grabbing, no fade from either wheel, and excellent directional stability until you lock up a wheel.

Acceleration is so powerful and smooth that care must really be taken not to break traction by turning it on too hard in the lower gears, even when extremely “tall” gearing is installed. Although the engine produces maximum power (105 bhp at the rear wheel) at a rather modest 7500 rpm, the power falls off rapidly above that figure, and maximum “safe” engine speed is 8000 rpm. Power delivery is smooth from 5500 rpm, and it really comes on strong at 6000 rpm. However, the engine will pull happily without hesitation from as low as 5000 rpm, making it delightfully predictable and easy to ride.

There is a sweeping left-hand corner at the test track which can be taken at about 70 mph in second gear; there I first learned what horsepower is all about. Feathering the throttle to keep the speed right (and to keep the rather hard compound racing tires from slipping) was necessary; the application of more throttle would step the rear end out as when riding a turn on a one-mile dirt track. That’s a great feeling, but not with clip-ons!

Checking the water temperature gauge was a little strange at first, but it never got above 65 deg. C, and the maximum allowable is 95 deg. C! After many laps of running, the top speeds always stayed within a mile or two/hr. of each other.

The following Sunday we went to the test track for my last ride before Daytona. The wind was extraordinarily calm, so we fitted a one-tooth-smaller sprocket to the rear wheel, and after several laps I pulled in to get yet another smaller sprocket. Then I was told that I’d turned 173 mph! They informed me there were no smaller sprockets in the truck and that the factory was closed on Sunday.

I feel that 175 mph is within reason, however, and now all the Suzuki team has to worry about are tires and chains. Both of which the TR750 consumes with relish! [Q]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue