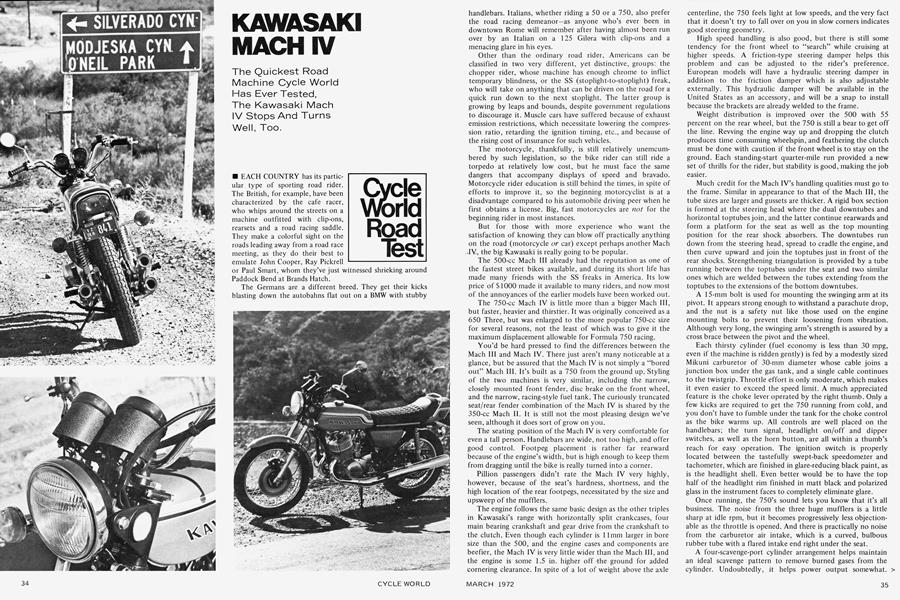

KAWASAKI MACH IV

Cycle World Road Test

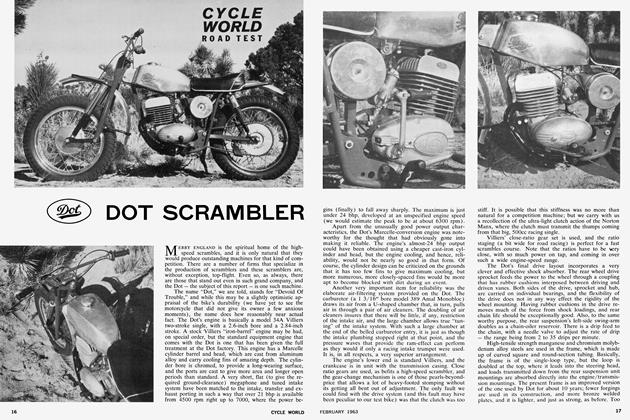

The Quickest Road Machine Cycle World Has Ever Tested, The Kawasaki Mach IV Stops And Turns Well, Too.

EACH COUNTRY has its particular type of sporting road rider. The British, for example, have been characterized by the cafe racer, who whips around the streets on a machine outfitted with clip-ons, rearsets and a road racing saddle. They make a colorful sight on the roads leading away from a road race meeting, as they do their best to emulate John Cooper, Ray Pickrell or Paul Smart, whom they've just witnessed shrieking around Paddock Bend at Brands Hatch. The Germans are a different breed. They get their kicks blasting down the autobahns flat out on a BMW with stubby handlebars. Italians, whether riding a 50 or a 750, also prefer the road racing demeanor-as anyone who's ever been in downtown Rome will remember after having almost been run over by an Italian on a 125 Gikra with clip-ons and a menacing glare in his eyes.

Other than the ordinary road rider, Americans can be classified in two very different, yet distinctive, groups: the chopper rider, whose machine has enough chrome to inflict temporary blindness, or the SS (stoplight-to-stoplight) freak, who will take on anything that can be driven on the road for a quick run down to the next stoplight. The latter group is growing by leaps and bounds,. despite government regulations to discourage it. Muscle cars have suffered because of exhaust emission restrictions, which necessitate lowering the compres sion ratio, retarding the ignition timing, etc., and because of the rising cost of insurance for such vehicles.

The motorcycle, thankfully, is still relatively unemcum bered by such legislation, so the bike rider can still ride a torpedo at relatively low cost, but he must face the same dangers that accompany displays of speed and bravado. Motorcycle rider education is still behind the times, in spite of efforts to improve it, so the beginning motorcyclist is at a disadvantage compared to his automobile driving peer when he first obtains a license. Big, fast motorcycles are not for the beginning rider in most instances.

But for those with more experience who want the satisfaction of knowing they can blow off practically anything on the road (motorcycle or car) except perhaps another Mach IV, the big Kawasaki is really going to be popular.

The 500-cc Mach III already had the reputation as one of the fastest street bikes available, and during its short life has made many friends with the SS freaks in America. Its low price of $1000 made it available to many riders, and now most of the annoyances of the earlier models have been worked out. The 750-cc Mach IV is little more than a bigger Mach III, but faster, heavier and thirstier. It was originally conceived as a 650 Three, but was enlarged to the more popular 750-cc size for several reasons, not the least of which was to give it the maximum displacement allowable for Formula 750 racing.

You'd be hard pressed to find the differences between the Mach III and Mach IV. There just aren't many noticeable at a glance, but be assured that the Mach IV is not simply a "bored out" Mach III. It's built as a 750 from the ground up. Styling of the two machines is very similar, including the narrow, closely mounted front fender, disc brake on the front wheel, and the narrow, racing.style fuel tank. The curiously truncated seat/rear fender combination of the Mach IV is shared by the 350-cc Mach II. It is still not the most pleasing design we've seen, although it does sort of grow on you.

The seating position of the Mach IV is very comfortable for even a tall person. Handlebars are wide, not too high, and offer good control. Footpeg placement is rather far rearward because of the engine's width, but is high enough to keep them from dragging until the bike is really turned into a corner. Pillion passengers didn't rate the Mach IV very highly, however, because of the seat's hardness, shortness, and the high location of the rear footpegs, necessitated by the size and upsweep of the mufflers.

The engine follows the same basic design as the other triples in Kawasaki's range with horizontally split crankcases, four main bearing crankshaft and gear drive from the crankshaft to the clutch. Even though each cylinder is 11mm larger in bore size than the 500, and the engine cases and components are beefier, the Mach IV is very little wider than the Mach III, and the engine is some 1.5 in. higher off the ground for added Qornering clearance. In spite of a lot of weight above the axle centerline, the 750 feels light at low speeds, and the very fact that it doesn't try to fall over on you in slow corners indicates good steering geometry.

1-ugh speed handling is also good, but there is still some tendency for the front wheel to "search" while cruising at higher speeds. A friction-type steering damper helps this problem and can be adjusted to the rider's preference. European models will have a hydraulic steering damper in addition to the friction damper which is also adjustable externally. This hydraulic damper will be available in the United States as an accessory, and will be a snap to install because the brackets are already welded to the frame.

Weight distribution is improved over the 500 with 55 percent on the rear wheel, but the 750 is still a bear to get off the line. Revving the engine way up and dropping the clutch produces time consuming wheelspin, and feathering the clutch must be done with caution if the front wheel is to stay on the ground. Each standing-start quarter-mile run provided a new set of thrills for the rider, but stability is good, making the job easier.

Much credit for the Mach tV's handling qualities must go to the frame. Similar in appearance to that of the Mach III, the tube sizes are larger and gussets are thicker. A rigid box section is formed at the steering head where the dual downtubes and horizontal toptubes join, and the latter continue rearwards and form a platform for the seat as well as the top mounting position for the rear shock absorbers. The downtubes run down from the steering head, spread to cradle the engine, and then curve upward and join the toptubes just in front of the rear shocks. Strengthening triangulation is provided by a tube running between the toptubes under the seat and two similar ones which are welded between the tubes extending from the toptubes to the extensions of the bottom downtubes.

A 15-mm bolt is used for mounting the swinging arm at its pivot. It appears strong enough to withstand a parachute drop, and the nut is a safety nut like those used on the engine mounting bolts to prevent their loosening from vibration. Although very long, the swinging arm's strength is assured by a cross brace between the pivot and the wheel.

Each thirsty cylinder (fuel economy is less than 30 mpg, even if the machine is ridden gently) is fed by a modestly sized Mikuni carburetor of 30-mm diameter whose cable joins a junction box under the gas tank, and a single cable continues to the twistgrip. Throttle effort is only moderate, which makes it even easier to exceed the speed limit. A much appreciated feature is the choke lever operated by the right thumb. Only a few kicks are required to get the 750 running from cold, and you don't have to fumble under the tank for the choke control as the bike warms up. All controls are well placed on the handlebars; the turn signal, headlight on/off and dipper switches, as well as the horn button, are all within a thumb's reach for easy operation. The ignition switch is properly located between the tastefully swept-back speedometer and tachometer, which are finished in glare-reducing black paint, as is the headlight shell. Even better would be to have the top half of the headlight rim finished in matt black and polarized glass in the instrument faces to completely eliminate glare.

Once running, the 750's sound lets you know that it's all business. The noise from the three huge mufflers is a little sharp at idle rpm, but it becomes progressively less objection able as the throttle is opened. And there is practically no noise from the carburetor air intake, which is a curved, bulbous rubber tube with a flared intake end right under the seat.

A four-scavenge-port cylinder arrangement helps maintain an ideal scavenge pattern to remove burned gases from the cylinder. Undoubtedly, it helps power output somewhat. > Two-ring pistons ride on needle bearings at the small ends, and the big ends ride on roller bearings around the crank pins as is common practice on -two-cycle motorcycle engines. Departing from common two-stroke practice is the crankshaft, which employs half-circle or "pork chop"-style flywheels. This reduces the pressure available in the crankcase for pumping the new charge of fuel/air mixture into the combustion chamber, but the pressure available at high rpm with a full-circle style flywheel often gets so great on a large-capacity cylinder that sealing the crankcase becomes a problem. The 750 features labyrinth seals between the flywheels and ordinary lip seals on the ends of the crankshaft which should be very long lasting. In addition, the "pork chop"-type flywheel is much easier to balance, which is one reason the Mach IV is so smooth.

Vibration is very low for a 750 Three, and what does come through becomes annoying at about 5000 rpm or 80 mph. Even then, only a small trace can be felt through the rubber-mounted handlebars; the rigid footpegs send up a stronger signal. High speed cruising is generally very sedate until you turn up the loud handle, at which time the rear end squats down and both tach and speedo needles move upwards at a frightening rate. Top gear acceleration from 60 to 90 mph is unbelievable. In most instances it's not necessary to downshift to pass traffic.

With the exception of the gear shift pattern, which places neutral at the bottom of the shifting sequence, the transmis sion's operation is almost flawless. And for those who prefer to shift on the right-hand side, the shifter shaft extends through the right-hand case. Ball and needle bearings support the transmission shafts, and a drum-type shifter mechanism employs girdling shifter forks for smooth and positive opera tion. The gears themselves are enormous and should be practically unbreakable.

As placid, as tfle overall character 01 tiie M~Cfl IV Is, tnere is still some unwanted mechanical noise from the pistons, and, to a greater extent, from the clutch/transmission unit. The clutch, which is adequate to handle the 750's brutish horsepower, is driven from the crankshaft by straight-cut gears. The gears are inherently noisy, but things get pretty quiet when the clutch lever is pulled in, indicating the need for more work on the clutch.

However, several clutch adjustments were necessary during our acceleration runs, and the clearance between the clutch lever and its body stayed almost the same even after the machine had been allowed to cool down. The seven driven (bonded) plates and seven drive (steel) plates, which includes the pressure plate, are very large, but more could be used for an extra margin of safety.

The power band is extremely wide due to fairly mild port timing, and the gear ratios are ideally suited to keeping the engine "on the boil." In fact, a couple of gears could be left out and wouldn't be missed at all by the ordinary road rider. Firm in action, the front forks have more than adequate travel and damping action and contribute to the precise steering at almost all speeds. Gone is the tendency of the early Mach III to "pogo," and the rear suspension units provide fine operation, either solo or riding double.

Whatever we may find fault with, it certainly isn't the brakes. The enormous front disc measures over 11.5 in. in diameter and provides some 63.3 sq. in. of effective braking power. The rear is very large also and never showed any touchiness or pronounced fading. The front brake lever begins pressing on the master cylinder after only a short amount of travel, making it difficult for a person with small hands to get a firm grip on the lever. A lever with an adjustment screw would be preferable, so the front brake lever's engaging point with the master cylinder could be varied.

Lubricating oil is fed to the engine by a plunger-type pump driven from the right-hand end of the crankshaft. The pump's output is controlled both by the engine's rpm and the amount of throttle opening. From the pump, oil is directed through plastic lines to a fitting behind each crank chamber, where it passes through a one-way check valve to a passage which "T's," or splits. One direction leads to the cylinders' transfer ports and the other direction leads to the main bearings and big end bearings. A slinger on each crankpin allows the oil to spray upwards to lubricate the small end bearings and cylinder walls before being burned and expelled out the exhaust pipes. All production models will be delivered with an "endless" rear chain for greater safety. With so much torque available, an ordinary chain with a master link (the weakest link in any chain) would most likely give less than satisfactory service. Installing an "endless" chain requires some trouble because the transmission sprocket, swinging arm and rear wheel have to be removed to replace it. However, the Mach IV is fitted with a manually operated chain oiler with the plunger under the left-hand side of the seat so that the chain may be lubricated while riding, increasing its life.

Finish and detailing are typically excellent. Chrome plating is rich and the paint is practically flawless. Some of the welds on the frame look a little cobby, but the entire package is very pleasing. The Mach IV rates as the ultimate stud bike now available in terms of raw power and sheer speed, although it does lack the refinement of some strictly touring machines. If being the fastest on your block appeals to you, so will the Mach IV!

KAWASAKI MACH IV

$1386

View Full Issue

View Full Issue