NSU SUPERMAX

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

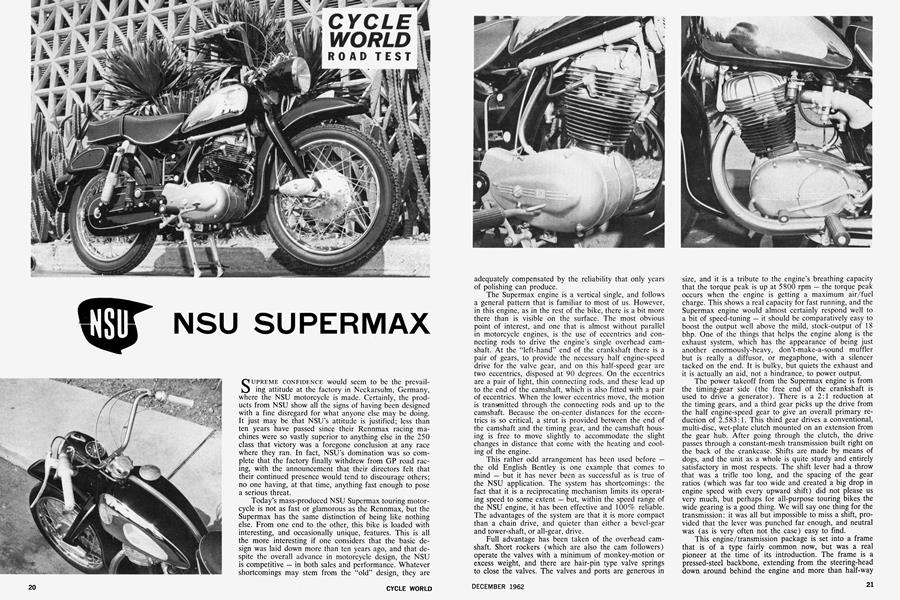

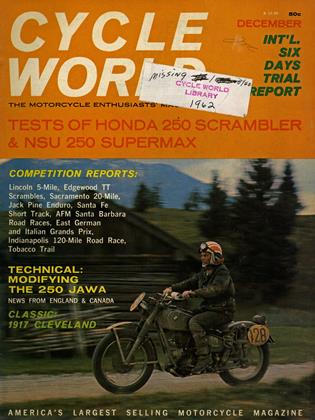

SUPREME CONFIDENCE would seem to be the prevailing attitude at the factory in Neckarsulm, Germany, where the NSU motorcycle is made. Certainly, the products from NSU show all the signs of having been designed with a fine disregard for what anyone else may be doing. It just may be that NSU's attitude is justified; less than ten years have passed since their Rennmax racing machines were so vastly superior to anything else in the 250 class that victory was a foregone conclusion at any race where they ran. In fact, NSU's domination was so complete that the factory finally withdrew from GP road racing, with the announcement that their directors felt that their continued presence would tend to discourage others; no one having, at that time, anything fast enough to pose a serious threat.

Today’s mass-produced NSU Supermax touring motorcycle is not as fast or glamorous as the Rennmax, but the Supermax has the same distinction of being like nothing else. From one end to the other, this bike is loaded with interesting, and occasionally unique, features. This is all the more interesting if one considers that the basic design was laid down more than ten years ago, and that despite the overall advance in motorcycle design, the NSU is competitive — in both sales and performance. Whatever shortcomings may stem from the “old” design, they are adequately compensated by the reliability that only years of polishing can produce.

The Supermax engine is a vertical single, and follows a general pattern that is familiar to most of us. However, in this engine, as in the rest of the bike, there is a bit more there than is visible on the surface. The most obvious point of interest, and one that is almost without parallel in motorcycle engines, is the use of eccentrics and connecting rods to drive the engine’s single overhead camshaft. At the “left-hand” end of the crankshaft there is a pair of gears, to provide the necessary half engine-speed drive for the valve gear, and on this half-speed gear are two eccentrics, disposed at 90 degrees. On the eccentrics are a pair of light, thin connecting rods, and these lead up to the end of the camshaft, which is also fitted with a pair of eccentrics. When the lower eccentrics move, the motion is transmitted through the connecting rods and up to the camshaft. Because the on-center distances for the eccentrics is so critical, a strut is provided between the end of the camshaft and the timing gear, and the camshaft housing is free to move slightly to accommodate the slight changes in distance that come with the heating and cooling of the engine.

This rather odd arrangement has been used before — the old English Bentley is one example that comes to mind — but it has never been as successful as is true of the NSU application. The system has shortcomings: the fact that it is a reciprocating mechanism limits its operating speed to some extent — but, within the speed range of the NSU engine, it has been effective and 100% reliable. The advantages of the system are that it is more compact than a chain drive, and quieter than either a bevel-gear and tower-shaft, or all-gear, drive.

Full advantage has been taken of the overhead camshaft. Short rockers (which are also the cam followers) operate the valves with a minimum of monkey-motion or excess weight, and there are hair-pin type valve springs to close the valves. The valves and ports are generous in size, and it is a tribute to the engine’s breathing capacity that the torque peak is up at 5800 rpm — the torque peak occurs when the engine is getting a maximum air/fuel charge. This shows a real capacity for fast running, and the Supermax engine would almost certainly respond well to a bit of speed-tuning — it should be comparatively easy to boost the output well above the mild, stock-output of 18 bhp. One of the things that helps the engine along is the exhaust system, which has the appearance of being just another enormously-heavy, don’t-make-a-sound muffler but is really a diffusor, or megaphone, with a silencer tacked on the end. It is bulky, but quiets the exhaust and it is actually an aid, not a hindrance, to power output. This engine/transmission package is set into a frame that is of a type fairly common now, but was a real pioneer at the time of its introduction. The frame is a pressed-steel backbone, extending from the steering-head down around behind the engine and more than half-way back over the rear wheel, forming a large part of the rear fender. These pressed frames do not look as light, or strong, as the type fabricated from tubes, but they can be as good, or better. A pressing does not have to have a constant section, like a drawn tube, and the “backbone” may be varied in depth to meet load requirements. This has been done on the NSU frame, with the result that it is light, and strong, and leaves the engine/transmission unit hanging out where it can easily be serviced, or removed for overhaul. And, in the NSU, the frame is also pressed into service as a dust-trap and air-silencer for the carburetor. Air for the carburetor is pulled through a wet (oil) filter, but it first comes in through the frame.

The power takeoff from the Supermax engine is from the timing-gear side (the free end of the crankshaft is used to drive a generator). There is a 2:1 reduction at the timing gears, and a third gear picks up the drive from the half engine-speed gear to give an overall primary reduction of 2.583:1. This third gear drives a conventional, multi-disc, wet-plate clutch mounted on an extension from the gear hub. After going through the clutch, the drive passes through a constant-mesh transmission built right on the back of the crankcase. Shifts are made by means of dogs, and the unit as a whole is quite sturdy and entirely satisfactory in most respects. The shift lever had a throw that was a trifle too long, and the spacing of the gear ratios (which was far too wide and created a big drop in engine speed with every upward shift) did not please us very much, but perhaps for all-purpose touring bikes the wide gearing is a good thing. We will say one thing for the transmission: it was all but impossible to miss a shift, provided that the lever was punched far enough, and neutral was (as is very often not the case) easy to find.

The front forks are of pressed-steel, too. They terminate at their lower end in a sort of fairing, and these mask the suspension’s leading links. Within the fork legs there are conventional spring/damper units and, on the brake backing-plate side there is a single link that takes the thrust from braking torque. Today, most manufacturers have gone to telescopic forks, and there are good reasons for that, but the very low unsuspended mass provided by the NSU’s system has its merits, too. Also, the NSU’s solid forks are very strong.

The rear suspension is quite orthodox, with (what else) pressed steël trailing swing-arms and a pair of adjustable (for load) spring/damper units. Early versions of the Max had a single spring and damper mounted up inside the frame, but they have abandoned that for the more conventional layout. The suspension-is, both front

and rear, just about medium in stiffness, being neither spongy nor harsh.

The Supermax’s brakes are of the full-width variety, and are of light alloy with cast-iron liners. Single leading shoe actuation is provided for both brakes. In action, the brakes are good, and very smooth, although not outstandingly powerful. They are, of course, more than adequate, for the Supermax’s level of performance.

For all around use, the Supermax is a very satisfactory motorcycle. It is, above everything else, a sturdy and completely reliable — we know of no other bike that one could ride away on and be more certain of getting to one’s destination without incident. Not only that, but it is a comfortable machine, with the bars high enough, the seat wide enough and the pegs mounted far enough forward to give the rider a nice, relaxed position. It handles moderately well, goes moderately fast (a few minor changes will convert it into much more of a racing bike, if that is what one wants) and it is immoderately stout of heart. There are few machines, either twoor fourwheeled, that will provide the kind of solid, never-miss-abeat that one gets with the NSU Supermax.

We obtained our test machine from Jay Richter, at West Valley Cycle Sales in Canoga Park, California, (Western U.S. Distributors for NSU) which he uses for his own personal transportation. It had several thousand miles showing on the odometer and was obviously well broken in. The specimen shown in the photographs on these pages is a new machine off their showroom floor. •

NSU

SUPERMAX

$699

SPECIFICATIONS

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

The Service Department

December 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

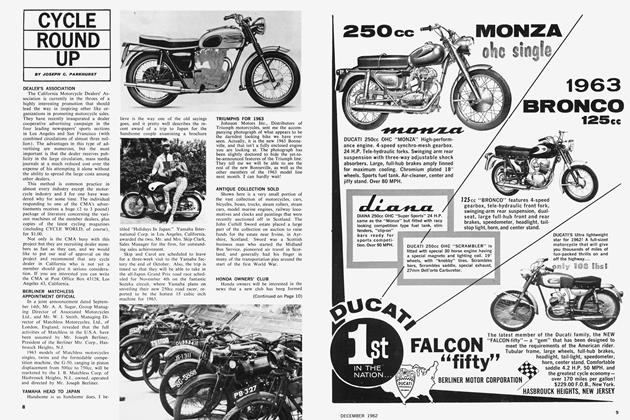

Cycle Round Up

December 1962 By Joseph C. Parkhurst -

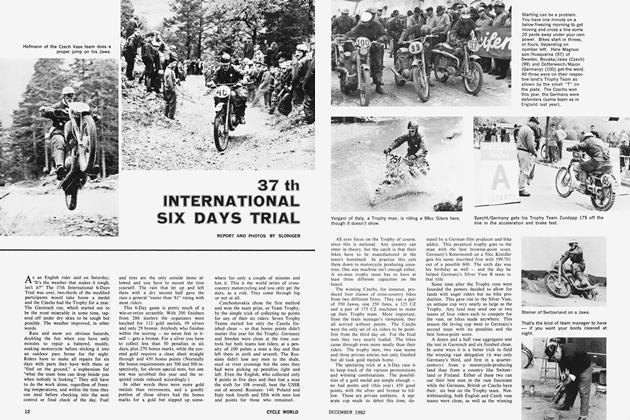

37 Th International Six Days Trial

December 1962 By Sloniger -

Modifying the Jawa 250 For Road Racing

December 1962 -

A Cycle World Classic

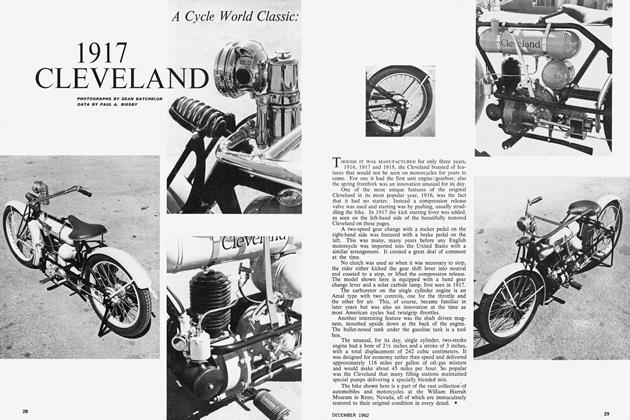

A Cycle World Classic1917 Cleveland

December 1962 By Paul A. Bigsby -

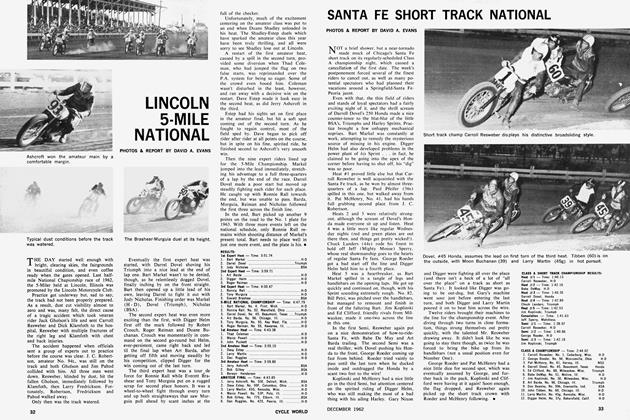

Lincoln 5-Mile National

December 1962 By David A. Evans