HISTORY OF FN

FROM WORLD CHAMPION TO VIRTUAL UNKNOWN IN 14 YEARS.

DESPITE LACK OF fame today, FN has earned a particularly prominent place in motorcycle history, and their factory archives contain many relics of past glories that are the envy of more famous marques.

The big reason why FN is virtually unknown today is that they have not produced any motorcycles since the middle 1960s. Another reason is they have never courted the English speaking market, preferring instead to market their wares in the central European countries that so desperately needed an inexpensive and reliable mode of transportation over most of the first half of this century.

Another reason so little is heard of FN these days is that they were so modest about their magnificent engineering achievements and successes in the world of competition. This is surprising, since FN has a remarkable record in international competition, with their engineering often being unique and sometimes far ahead of their rivals.

The story of the Fabrique Nationale d’ Armes de Guerre began in 1889 when a factory was built at Herstal, in Liege, for the purpose of producing all types of armaments. In 1895 the company broadened their scope to include bicycle frames, and in 1898 they began producing complete bicycles.

In 1901 the infant concern made their really big step by motorizing their bicycle with a 133-cc single-cylinder engine that churned out 114 bhp. This tiny thumper had an inlet-over-exhaustvalve design in which the inlet valve was sucked open by the downstroke of the piston. The bore and stroke was 50 by 68mm, and a leather belt drive on a wooden pulley propelled the beast.

This primitive motorbike was as reliable as any in those days, and a total of 300 left the assembly line that first year of production. At that time there were many other Belgian companies trying to produce a reliable motorbike-Sarolea, Gillet, Brondoit, CIE, Marck, Ninuer, PA, and Pieper. Of all these, only FN was destined to endure to the 1960s.

In 1903 the primitive Single was enlarged to 188-cc by increasing the engine’s bore and stroke to 57 by 74mm. These changes provided a 2 bhp output. In 1904 the engine was again enlarged to 300cc by using 70 by 80mm measurements; sales zoomed to 600 units. In 1904 the Single also acquired a longer wheelbase, a sprung front fork, and a new magneto which made starting easier. An oil tank and a mechanical oil pump were also adopted, an improvement over the hand pump system so popular then.

By then FN had become quite prominent in the motorcycle field, so in 1905 they made a bold bid to assume undisputed leadership with the introduction of a new four-cylinder model. This 362-cc engine had a bore and stroke of 45 by 57mm, and the inlet-over-exhaust design was retained. In 1906 the engine was punched out to 410cc, but the bike still had no clutch. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about this Four was shaft drive, a natural move considering the in-line mounting of the engine.

In 1908 the fabulous Four was considerably modernized by the use of a clutch (the lever was on the handlebar), a cradle frame, an internal expanding brake, and a front fork with an enclosed

compression spring. Because it was a single speeder, pedals were still used for hills and starting. This early Four proved to be an exceptionally sound design, which was convincingly demonstrated by R.O. Clark when he finished 3rd in the 1908 Isle of Man TT twin-cylinder class. It is interesting to note that this is one of only four appearances the marque made in the colorful TT, and on this occasion the Four caused much consternation among the officials on how to enter it in the twin-cylinder class.

The big Four was followed in 1909 by a 247-cc Single in which the in-line crankshaft connected to a shaft drive, but by then the company was converting to the “modern” side-valve design. Sales moved to 2625 units in 1911, 3256 in 1912, and 2812 in 1913. The export business had also been developed to no less than 41 countries, and FN became a leader in the industry. Then came World War I, which brought the near destruction of the factory.

Production resumed in 1919 with the Four (which had acquired a two-speed gearbox in 1913), and a 285-cc Single with a mechanically operated i.o.e. design. The bore and stroke was 65 by 86mm. In 1920 the Four was increased to 748cc by using 52 by 88mm measurements.

UNIT CONSTRUCTION

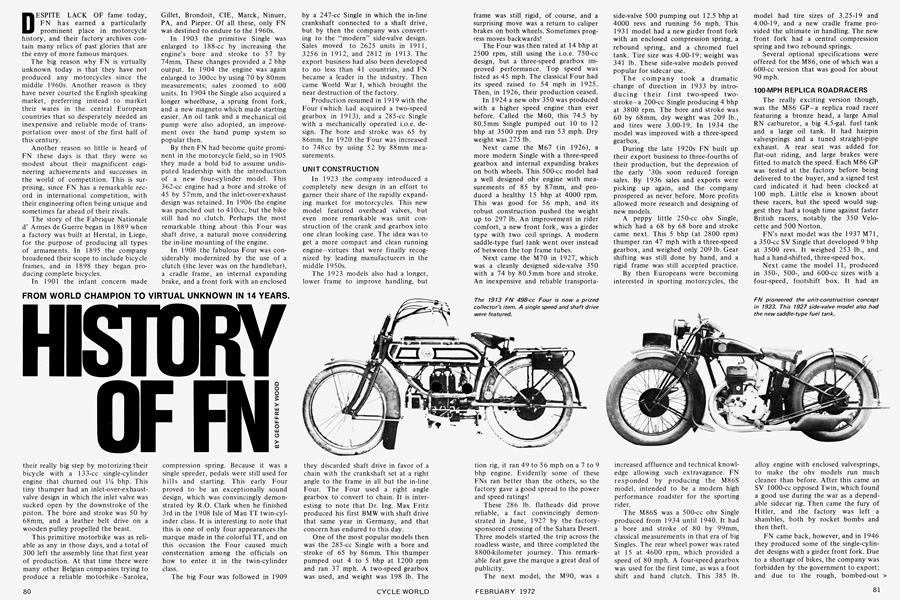

In 1923 the company introduced a completely new design in an effort to garner their share of the rapidly expanding market for motorcycles. This new model featured overhead valves, but even more remarkable was unit construction of the crank and gearbox into one clean looking case. The idea was to get a more compact and clean running engine—virtues that were finally recognized by leading manufacturers in the middle 1950s.

The 1923 models also had a longer, lower frame to improve handling, but they discarded shaft drive in favor of a chain with the crankshaft set at a right angle to the frame in all but the in-line Four. The Four used a right angle gearbox to convert to chain. It is interesting to note that Dr. Ing. Max Fritz produced his first BMW with shaft drive that same year in Germany, and that concern has endured to this day.

One of the most popular models then was the 285-cc Single with a bore and stroke of 65 by 86mm. This thumper pumped out 4 to 5 bhp at 1200 rpm and ran 37 mph. A two-speed gearbox was used, and weight was 198 lb. The frame was still rigid, of course, and a surprising move was a return to caliper brakes on both wheels. Sometimes progress moves backwards!

The Four was then rated at 14 bhp at 2500 rpm, still using the i.o.e. 750-cc design, but a three-speed gearbox improved performance. Top speed was listed as 45 mph. The classical Four had its speed raised to 54 mph in 1925. Then, in 1926, their production ceased.

In 1924 a new ohv 350 was produced with a higher speed engine than ever before. Called the M60, this 74.5 by 80.5mm Single pumped out 10 to 12 bhp at 3500 rpm and ran 53 mph. Dry weight was 275 lb.

Next came the M67 (in 1926), a more modern Single with a three-speed gearbox and internal expanding brakes on both wheels; This 500-cc model had a well designed ohv engine with measurements of 85 by 87mm, and produced a healthy 15 bhp at 4000 rpm. This was good for 56 mph, and its robust construction pushed the weight up to 297 lb. An improvement in rider comfort, a new front fork, was a girder type with two coil springs. A modern saddle-type fuel tank went over instead of between the top frame tubes.

Next came the M70 in 1927', which was a cleanly designed side-valve 350 with a 74 by 80.5mm bore and stroke. An inexpensive and reliable transportation rig, it ran 49 to 56 mph on a 7 to 9 bhp engine. Evidently some of these FNs ran better than the others, so the factory gave a good spread to the power and speed ratings!

These 286 lb. flatheads did prove reliable, a fact convincingly demonstrated in June, 1927 by the factorysponsored crossing of the Sahara Desert. Three models started the trip across the roadless waste, and three completed the 8800-kilometer journey. This remarkable feat gave the marque a great deal of publicity.

The next model, the M90, was a side-valve 500 pumping out 12.5 bhp at 4000 revs and running 56 mph. This 1931 model had a new girder front fork with an enclosed compression spring, a rebound spring, and a chromed fuel tank. Tire size was 4.00-19; weight was 341 lb. These side-valve models proved popular for sidecar use.

The company took a dramatic change of direction in 1933 by introducing their first two-speed twostroke—a 200-cc Single producing 4 bhp at 3800 rpm. The bore and stroke was 60 by 68mm, dry weight was 209 lb., and tires were 3.00-19. In 1934 the model was improved with a three-speed gearbox.

During the late 1920s FN built up their export business to three-fourths of their production, but the depression of the early ’30s soon reduced foreign sales. By 1936 sales and exports were picking up again, and the company prospered as never before. More profits allowed more research and designing of new models.

A peppy little 250-cc ohv Single, which had a 68 by 68 bore and stroke came next. This 5 bhp (at 2800 rpm) thumper ran 47 mph with a three-speed gearbox, and weighed only 209 lb. Gear shifting was still done by hand, and a rigid frame was still accepted practice.

By then Europeans were becoming interested in sporting motorcycles, the increased affluence and technical knowledge allowing such extravagance. FN responded by producing the M86S model, intended to be a modern high performance roadster for the sporting rider.

The M86S was a 500-cc ohv Single produced from 1934 until 1940. It had a bore and stroke of 80 by 99mm, classical measurements in that era of big Singles. The rear wheel power was rated at 15 at 4600 rpm, which provided a speed of 80 mph. A four-speed gearbox was used for the first time, as was a foot shift and hand clutch. This 385 lb. model had tire sizes of 3.25-19 and 4.00-19, and a new cradle frame provided the ultimate in handling. The new front fork had a central compression spring and two rebound springs.

Several optional specifications were offered for the M86, one of which was a 600-cc version that was good for about 90 mph.

100-MPH REPLICA ROADRACERS

The really exciting version though, was the M86 GP—a replica road racer featuring a bronze head, a large Amal RN carburetor, a big 4.5-gal. fuel tank and a large oil tank. It had hairpin valvesprings and a tuned straight-pipe exhaust. A rear seat was added for flat-out riding, and large brakes were fitted to match the speed. Each M86 GP was tested at the factory before being delivered to the buyer, and a signed test card indicated it had been clocked at 100 mph. Little else is known about these racers, but the speed would suggest they had a tough time against faster British' racers, notably the 350 Velocette and 500 Norton.

FN’s next model was the 1937 M71, a 350-cc SV Single that developed 9 bhp at 3500 revs. It weighed 253 lb., and had a hand-shifted, three-speed box.

Next came the model 11, produced in 350-, 500-, and 600-cc sizes with a four-speed, footshift box. It had an alloy engine with enclosed valvesprings, to make the ohv models run much cleaner than before. After this came an SV 1000-cc opposed Twin, which found a good use during the war as a dependable sidecar rig. Then came the fury of Hitler, and the factory was left a shambles, both by rocket bombs and then theft.

FN came back, however, and in 1946 they produced some of the single-cylinder designs with a girder front fork. Due to a shortage of bikes, the company was forbidden by the government to export; and due to the rough, bombed-out roads, FN decided to investigate improving their suspension system. The new model, called simply the Type 13, was destined to go through several stages of development.

The Type 13, in 250-cc, 350-cc, and 450-cc sizes, had bore and stroke measurements of 68 by 68mm, 74 by 80mm, and 84.5 by 80mm respectively. Most were ohv with an alloy head, but the 350 and 450 sizes were also available in side-valve trim. The horsepower of the three ohv models was listed as 9, 11, and 17.5 respectively, with speeds of 65, 68, and 78 mph. The 250 weighed 304 lb. and the big 450 weighed 3 10 lb.

Without a doubt, though, the most unusual item of the Type 13 was the suspension—rubber bands both front and rear. The rear featured a pivoted fork hinged at the bottom and hooked at the top to a pair of rubber snubbers.

The whole fork pivoted forward at the top in an arc. The front end had a wild trailing link setup with two large rubber bands, and an immovable tubular fork held everything in place. All of the models were produced with these forks, but a rigid frame SV 350 was available in the event that a rubber band rear suspension wasn’t appealing.

These type 13s continued in production with a new telescopic front fork in 1953, although the rubber band front fork was available until 1954. Then modern technology finally put the idea to rest forever.

In 1953 FN produced a new 175-cc two-stroke Single, with a modern swinging-arm frame. This 50-mph model was joined by 125and 200-cc versions in 1955, but the 125 and 200 were produced with a plunger rear suspension in an effort to cut costs. In 1956 a 200-cc swinging-arm model was produced, along with a 50-cc motorized bicycle and a sleek 250-cc Twin.

In the 1958 brochure there were only the 175and 250-cc two-strokes, however. The days of the big Singles had come to an end, a sad time for FN enthusiasts, since the lusty thumpers had been very good since 1954 when a swinging-arm frame and full-width alloy hubs made their debut. The reason for dropping the more powerful Singles was sheer economics; the standard of living in Belgium had risen so much that the people had parked their bikes and purchased automobiles. With their market gone, FN naturally focused on producing inexpensive two-stroke lightweights for the young at heart. Another FN era thus came to an end.

The 1958 brochure did have one interesting model, however, the 175-cc Trial, a clean little bog wheel which achieved a fair degree of success. The trialer came with an upswept exhaust, knobby tires, a raised front fender, and a frame with substantial ground clearanee.

During the middle ’50s FN also designed a beautiful ohc 500-cc Twin, intended to be a luxurious roadster for the discriminating buyer. The engine developed 26 bhp at 6000 rpm; top speed was given as 84 mph. The declining market prevented FN from ever going ahead with production though.

The home market continued to decline, and foreign competition became fierce for FN in the early ’60s. In 1960, production of the 250 ceased; in 1961 they gave up the 175. This left only the 75-cc motorbike, which, by 1962, accounted for only 40 percent of the 1957 sales volume. FN struggled a while longer, but finally decided to halt all bike production and concentrate on armaments and huge jet engines. A colorful era and a great marque were put to rest.

FN still lives on, however, in the legacy of FN’s sporting victories in road racing, record setting and motocross. For this chapter we must return to 1927 when Ing M. Flenri VanHout got the go-ahead to design some pukka racing bikes. Previously, FN had done virtually no competition; H. Huynen’s 1923 Belgian GP 350cc win was the only thing to crow about. In the IOM TT FNs retired in 1909 and 1931, and in 1914 they finished a lowly 33rd and 36th. Not very impressive, and it was up to Ing. VanHout to do something about it.

EUROPEAN GP ASSAULT

The racer was finally designed and produced, but the 1929 and 1930 seasons were somewhat of a failure due to unreliable machines and the need for some good riders. The bike was a clean ohc Single, produced in 350-, 500-, and 600-cc sizes. The big 600 was used mostly for sidecar racing.

The basic design had a chain-driven single cam and unit construction, with the inlet port at an angle for optimum cylinder charging. Hairpin valvesprings were used, and by 1934 an alloy cylinder and head were adopted. A rigid frame and girder front fork were standard practice then, but a pair of good sized brakes were cast into magnesium alloy hubs. A big 4.5-gal. fuel tank and large oil tank were fitted, and FN scorned the use of fenders in an effort to reduce weight. Very few tech specs are known about any of the pre-war FN racers due to the war damage at the factory, a sad fact for historians.

During the period of 1929-1933 the FN racers gained in both speed and reliability while the riders gained in skill. Many local races and minor grand prix events were won then, with the factory concentrating on the continental countries close to Belgium.

By 1934 the company was confident of their chances in the major grand prix events, and they soon began to show up with a team of 350and 500-cc Singles. In the Belgian Francorchamps race early in June, Pol Demeuter, Erick Haps and Rene Milhoux took the first three places in the 500-cc class, and Jules Tacheny went on to become Belgian champion that year.

The really big achievement came in the 350-cc Dutch TT, where Demueter and Haps took 1st and 2nd, and Milhoux gained a 6th Tnis great display of speed staggered the Norton team, accustomed to contending only with their arch-rival, Velocette. Demueter and Haps were later killed at Chemnitz in Germany, and the FN team then retired for the rest of the season.

In 1935 FN came back strongly, winning dozens of races in Belgium, Holland, France, Italy, Switzerland and Austria. The marque also won 1st and 2nd in the 500cc French GP at Montlehery (Milhoux and Charlier), plus a 350cc win by Collette.

By far the finest performance that year came in the Ulster Grand Prix, designated “The Grand Prix d’ Europe,” an honor given to one classic each year to signify that it was the year’s most important event. FN-mounted Ted Mellors led early in the race, but the great Jimmie Guthrie finally got his Norton ahead and pulled out a hard-earned 90.98-mph win. Milhoux finished 2nd at 89.11 mph, and Mellors came home 4th.

In 1936 FN continued to win literally hundreds of minor grand prix events on the continent at such nostalgic prewar circuits as Sambre et Meusse, de Floreffe and de Chaud Fontaine. The following year the record was not quite

so good, due probably to the fact that the rigid-frame FNs could not hold the road quite as well as the many new spring-frame models being tried out then. In 1938 and ’39 the record was even less impressive, with only a few minor GP wins each year.

During these years FN had observed the British Singles evolve into superb racing machines with good suspension systems and highly developed ohc engines. They had also observed the new supercharged Twins and Fours make their debut, proving just how competitive international racing had become.

The only answer was more speed, of course, so FN decided that they, too, would build a supercharged beast. The bike made its first appearance in 1937, a wicked looking Twin with a chain drive single overhead camshaft, a roots-type blower mounted behind the alloy cylinder, and a huge finned rear brake.

Very little is known of tech specs, but top speed was in excess of 130 mph, faster than the best Singles but still below the 140-150 mph speeds of the other blown beasts going then. More development was obviously needed to obtain higher performance, and a spring frame was necessary to improve road holding. As it transpired, the supercharged Twin was insufficiently developed; its few appearances usually ended in some blinding speed and then a mechanical failure. Then came the war, and blown beasts were never heard of again.

After the war FN forgot all about road racing and became infatuated with motocross—a sport in which they had achieved a fair turn of success during the late 1930s when it was first introduced to the continental countries. In 1947 the first Motocross des Nations was held in Holland, and all the Belgian riders were mounted on British machines. Within one year this was destined to change!

During 1947 the factory developed a motocross machine for their works team utilizing a pre-war ohc single-cylinder racing engine in a new “rubber snubber” frame with a bulky rubber band front fork. In 1947 a few wins were scored at home, but by 1948 Victor LeLoup began dominating the continental events on his way to several Dutch, Belgian and European championships.

The following few years LeLoup and Aguste Mingels became the terrors of motocross, so it was no surprise when Victor won the first official European Championship in 1952. By then everyone had quit laughing at the “rubber band” FNs, although by 1952 they did have an unusual plunger rear suspension.

FN was doing their homework, however. In 1953 they appeared with a modern looking swinging-arm model with a telescopic front fork. This scrambler was still rather huge, weighing about 370 lb., but it had gobs of power and was very reliable. The great Aguste Mingels won the prestigious European Championship in both 1953 and 1954, and other riders won national championships in many of the continental countries. LeLoup also finished in 4th place in the 1954 European title chase.

In 1955 FN slumped to 3rd in the championship behind the new and powerful BSA Gold Stars. It was not until 1958 that the marque again got back on top, when the dashing Rene Baeton convincingly won the championship that year; Hubert Scaillet was 5th.

These 1958 FNs were superb examples of the classical big Single; not until the end of the season did the company release any details of the model. That year the 85 by 87mm Single had a capacity of 494cc and still used the alloy chain-driven ohc design dreamed up in the 1920s. The bike weighed about 350 lb. and was quite a bit lower. A 3.0-gal. fuel tank was fitted. The primary drive was by straight cut gears to a Ferodo oil-bath clutch, and the full width alloy hubs had 185-mm brakes. The magneto was chain driven from the crankshaft, and the hairpin valvesprings were left exposed for cooling.

(Continued on page 119)

Continued from page 83

The engine had been steadily developed until it put out 45 bhp at 6125 rpm. Peak torque was at 4900 revs, and the engine produced about 29 bhp as low as 4000 rpm.

A magnificent machine for the task at hand, and by the end of 1958 FN had amassed a remarkable total of 395 victories in international motocross racing. The factory was in sales trouble by then due to a falling market, however, so it wasn’t economical to support a works team in motocross. The big Singles thus passed into the history books.

Road racing and motocross, however, weren’t FNs only successful racing endeavors. They also set several speed records during the 1930s. The bulk of these records were in the endurance categories of 5 kilometers up to 500 miles, since the FN Singles seemed to have more stamina at speed than just sheer speed. When the FIM published their official listing in October, 1935, FN held no less than 81 world records. Perhaps the most remarkable were the 5 kilo at 111.35 mph and the 85.8 mph mark for 12 hours in the 350cc class. Also impressive was the 96.53 mph speed for 500 miles in the lOOOcc class.

The record that FN was and still is the most proud of was the flying kilometer mark set on April 22, 1934 at Bonheyden, Belgium. Rene Milhoux, the rider, screamed through the traps on a 500-cc Single to record 138.9 mph. The bike’s only streamlining was a tiny nose cone, and FN still claims it is the fastest speed ever recorded by a Single in the record books. For a Single without a streamlined fairing, the statement is perhaps correct. At any rate, it was a remarkable achievement for a 500-cc thumper in 1934.

Since the 1930s FN has made no attempts to set speed records. By 1952 they were down to 21. By 1966 they held only one-the 10 kilo standing start for 500-cc sidecars at 96.13 mph. And so it is today—only one mark to represent such a proud era of motorcycle history.