REPORT FROM ITALY

CARLO PERELLI

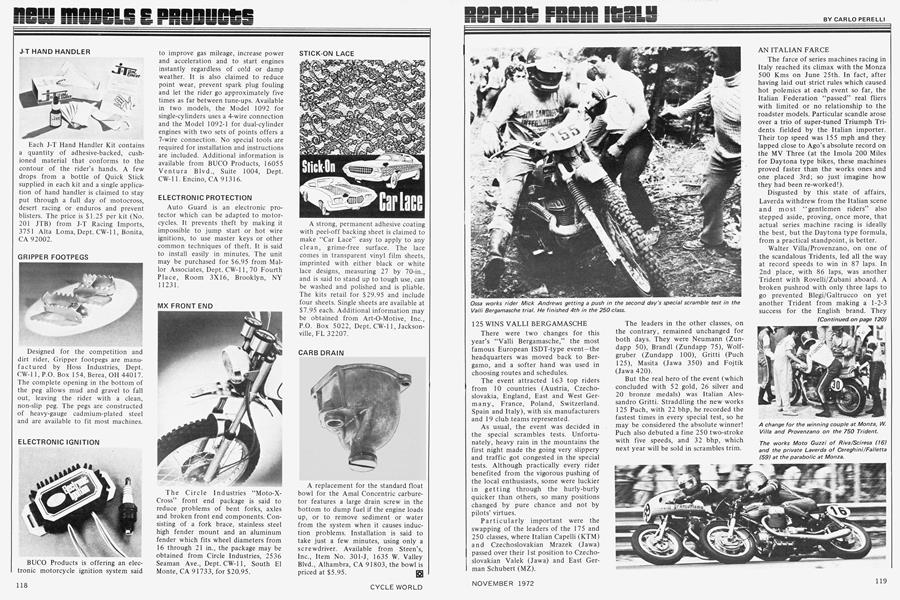

125 WINS VALLI BERGAMASCHE

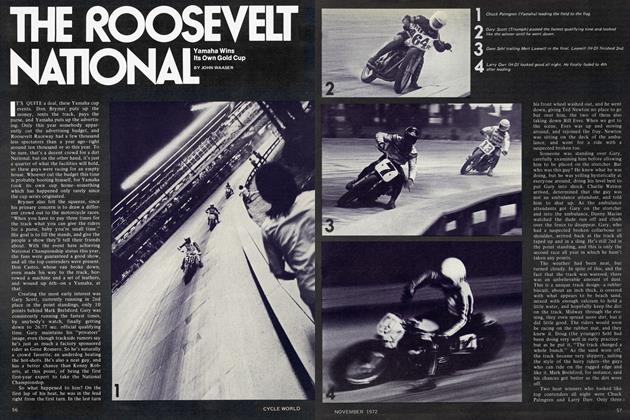

There were two changes for this year’s “Valli Bergamasche,” the most famous European ISDT-type event—the headquarters was moved back to Bergamo, and a softer hand was used in choosing routes and schedules.

The event attracted 163 top riders from 10 countries (Austria, Czechoslovakia, England, East and West Germany, France, Poland, Switzerland. Spain and Italy), with six manufacturers and 19 club teams represented.

As usual, the event was decided in the special scrambles tests. Unfortunately, heavy rain in the mountains the first night made the going very slippery and traffic got congested in the special tests. Although practically every rider benefited from the vigorous pushing of the local enthusiasts, some were luckier in getting through the hurly-burly quicker than others, so many positions changed by pure chance and not by pilots’ virtues.

Particularly important were the swapping of the leaders of the 175 and 250 classes, where Italian Capelli (KTM) and Czechoslovakian Mrazek (Jawa) passed over their 1st position to Czechoslovakian Valek (Jawa) and East German Schubert (MZ).

The leaders in the other classes, on the contrary, remained unchanged for both days. They were Neumann (Zundapp 50), Brandi (Zundapp 75), Wolfgruber (Zundapp 100), Gritti (Puch 125), Masita (Jawa 350) and Fojtik (Jawa 420).

But the real hero of the event (which concluded with 52 gold, 26 silver and 20 bronze medals) was Italian Alessandro Gritti. Straddling the new works 125 Puch, with 22 bhp, he recorded the fastest times in every special test, so he may be considered the absolute winner! Puch also debuted a fine 250 two-stroke with five speeds, and 32 bhp, which next year will be sold in scrambles trim.

AN ITALIAN FARCE

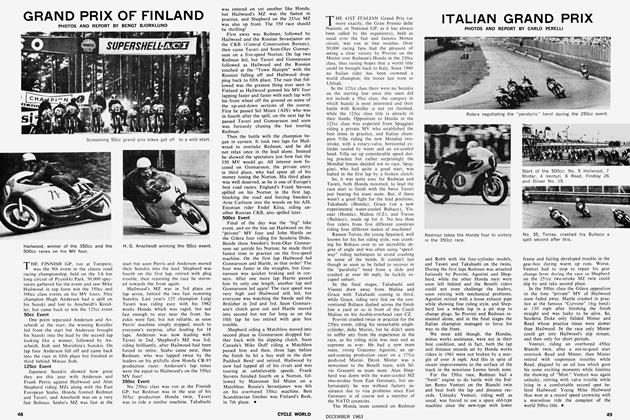

The farce of series machines racing in Italy reached its climax with the Monza 500 Kms on June 25th. In fact, after having laid out strict rules which caused hot polemics at each event so far, the Italian Federation “passed” real fliers with limited or no relationship to the roadster models. Particular scandle arose over a trio of super-tuned Triumph Tridents fielded by the Italian importer. Their top speed was 155 mph and they lapped close to Ago’s absolute record on the MV Three (at the Imola 200 Miles for Daytona type bikes, these machines proved faster than the works ones and one placed 3rd; so just imagine how they had been re-worked!).

Disgusted by this state of affairs, Laverda withdrew from the Italian scene and most “gentlemen riders” also stepped aside, proving, once more, that actual series machine racing is ideally the best, but the Daytona type formula, from a practical standpoint, is better.

Walter Villa/Provenzano, on one of the scandalous Tridents, led all the way at record speeds to win in 87 laps. In 2nd place, with 86 laps, was another Trident with Rovelli/Zubani aboard. A broken pushrod with only three laps to go prevented Blegi/Galtrucco on yet another Trident from making a 1-2-3 success for the English brand. They handed their position over to the Brambilla brothers (Moto Guzzi). Both couples finished within 85 laps. The private Laverda of Faccin/Rozza was fifth, five laps down. Success in the 500 class went to a Honda Twin Mariannini/Valentini, followed by a host of Suzukis. Luckily, in this class, no big rule cheating was recorded.

(Continued on page 120)

Continued from page 119

LAVERDA 1000 IS READY

Nearly two years after its introduction at the 1969 Milan Show, the biggest gun from Italy, the Laverda 1000, is now the triumphant center attraction in dealer showrooms.

It has been a long, tantalizing, but not useless wait. The bike has been improved, inside and out, and has been thoroughly tested in racing.

Wishing to tempt the enthusiasts with an even larger displacement bike than its well-known 750 Twin, early in 1969 Laverda decided for a “one thousand” and the technical team, headed by Dr. Francesco Laverda (founder of the factory in 1949), his son Ing. Massimo Laverda and “slide rule” responsible Luciano Zen, chose the three-cylinder layout, more to keep width within reasonable limits than for reasons of simplicity. “Another cylinder would have been no problem,” explains Ing. Massimo Laverda, “but we didn’t wish to exceed the Honda 750 Four width. In fact, our 1000 is slightly narrower than the Japanese multi, even though we allowed generous air passages between the cylinders.”

Of course, the 1000 borrows quite a bit of experience from the 750, especially in the power unit. Frame design, on the contrary, changed from “spine” to the more classic double cradle to allow a lower upper line and particularly a lower seat.

So, the 1000 is a chain driven sohc with electric starter, rubber belt driven generator in front of the crankcase, five-speed gearbox in unit, triplex primary drive, and multi-plate clutch on the left. Featuring 75 by 74mm bore and stroke dimensions, 30mm carburetors, 37mm (inlet) and 34mm (exhaust) valves, and 18-in. tires, this 1000 had a weight of 517 lb., a wheelbase of 59 in. and a claimed 75 bhp at 7000 rpm. Thanks to the new frame and a slightly shorter wheelbase, the 1000 proved to handle better than the 750 at once and, of course, it has a much “sweeter” power spread. But in spite of crankpin “spacing” at 120-deg., the powerhouse was not as free from vibration as expected.

(Continued on page 124)

Continued from page 120

So, during these two intensive years of development, much thought went into the vibration problem. It was found that because of the inevitable crankshaft width, the 120-deg. crankpin setting was not ideal and other layouts were tried. The best compromise was reached by putting the outer crankpins at 360-deg. and the middle one at 180-deg.

The timing system was also changed from single to dohc, always chain driven between the first and the second cylinder from the right. The move was dictated by the desire to offer an even more refined and exclusive technical layout, besides reducing mechanical losses. As a matter of fact, Laverda tests have shown that actuating the sohc system required no less than 50 percent more power than with the dohc layout! The modern system of the rubber belt to actuate the two cams was also tested with satisfying results, but then was scrapped for esthetical reasons. The rubber belt would have had to be placed outside the cylinders, enclosed in a large case on the right hand side, which looked very ugly.

Another important change, in favor of simplicity and efficiency, was to the electronic ignition (Bosch), with the breakerless apparatus and the generator all in one unit. This also made for a cleaner line.

Other basic modifications included a valve and carburetor diameter increase. The valves are now 38mm at the inlet and 35mm at the exhaust; the carburetors are new Dellortos, with cylindrical slides and “acceleration boosters,” with a choke diameter of 32mm. They breath from a plastic box containing a washable synthetic filter.

The three exhaust pipes are now converging into one silencer, on the left, and while this may not please some, it has proved good as a gas extractor and more harmonious for the sound. Besides, it weighs much less than three separate exhausts and silencers. Fiberglass has been used for the fuel tank and the side panels and this also aids in keeping weight down. The Laverda 1000 now tips the scale at 470 lb. (dry). No wonder that with the power increase obtained through the described modifications (now there is 80 bhp at 7200 rpm) the bike is effectively doing “over 130 mph” and is even hotter in acceleration!

The sturdy crankcase is horizontally split. The crankshaft is built-up in six pieces pressed together and the massive con-rods run at both ends over light alloy caged rollers. The crankshaft itself runs over two central heavy-duty roller bearings and two outside ball bearings plus a fifth external support (again of roller type) on the primary drive side, i.e. on the left. All crankshafts are thoroughly centered and balanced complete with con-rods and pistons.

The light alloy monoblocs for the heads and the cylinders have, as mentioned, large air ducts to aid cooling (barrels are in cast iron); moreover, there is quick oil circulation from a lower sump, through two separate circuits to the crankshaft and the dohc timing gear. Another point in favor of cooling is the 20-deg. cylinder inclination, exposing heads better to the wind.

The clutch housing is in light alloy, containing no less than 14 plates and the actuation is sufficiently soft.

This imposing power unit weighs 207 lb., only two more than the 750, but is not any less sturdy.

The bike is completed by the already known Laverda-patented brakes, featuring completely water and dirt-proof twin cam shoes, on Borrani light alloy rims with Dunlop K 81 TT 100 4.10-18 front and K 81 TT 1 10 4.25-18 rear tires. The 27 Ah-12V battery is placed under the saddle, in a position slightly lower than on the 750.

Instruments come from Japan, manual controls from England and finishing is good.

Alacrity and ingenuity are the keynotes at Laverda. Besides the 1000, two other new projects are well underway. A 480cc roadster, with twin cylinders (and double overhead cams and a five-speed gearbox) and, with absolute priority, a 250 420cc “off-road” two-stroke Single (with electron crankcase, five-speed gearbox, electronic ignition and enclosed rear chain). This latter is the first all-Italian two-stroke for dirt use.

The 750 SF, recently tested by CW, has also been amply revised, from experience gathered with the SF-C production racers. With bigger valves, new timing and exhaust system, power has stepped up from 60 to 66 bhp at 7100 rpm, with a possibility of up to 7600 rpm in top without any damage, thus attaining the ultimate of 125 mph. [o

View Full Issue

View Full Issue