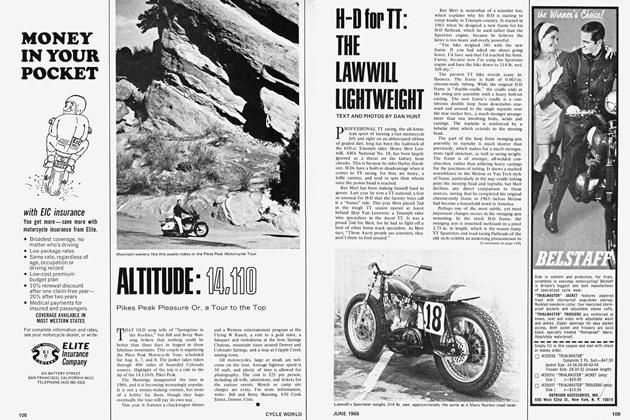

RIDING AN INNOVATIVE PROTOTYPE

YAMAHA'S COUNTERBALANCED, DISC-BRAKED, DOUBLE OVERHEAD CAM, TWO-CYLINDER AND (AHAH!) SOME WHAT SELF-DIAGNOSTIC MOTORCYCLE

DAN HUNT

IT MAY SEEM curious that Yamaha is spending money developing yet another four-stroke Twin, when the whole world is going to multis.

On the other hand, Yamaha may be smart and we don’t know it. After all, the big Twin, by which I mean any vertical Twin of 650 to 750cc displacement, is a popular size and shape of bike. Not too large for a hop up the block. Not so small that it can’t smoke off anything on up to about a small-block Corvette, costing four times as much money.

With the new TX750, Yamaha seems to have rethought the whole idea of what the Big Twin is supposed to be. Fiddling around with public preconceptions must make that company more than a little nervous.

A ride on the bike tells you that Yamaha is only incidentally pitting this Twin against other Twins—like Bonnevilles, Commandos, Lightnings and dohc 450s. The TX750’s real goal is a flanking assault on the expensive segment of the multi-cylinder which, of course, includes Honda’s 500 and 750 Fours, Kawasaki’s 750 Three, the British Triples, and Suzuki’s big waterpumper.

The idea of anyone competing against the big multis with a Twin may seem preposterous. Unless you can make the Twin as good as or almost as good as the multis and offer it for less money. For the multi class, what is good is “smooth.” And you know that typical vertical Twins are inherently not smooth. They vibrate, either because of primary imbalance created as the pistons churn up-and-down in unison, or because of eccentric vibration patterns created by 180-degree crankshaft layouts.

Many ways have been contrived to civilize the Twin. BMW succeeded in fair fashion by opposing cylinders horizontally and tolerating a small amount of rocking couple and throttleinduced torque reaction. Harley-Davidson went to a 45-degree V pattern and didn’t succeed at all. Moto Guzzi and Ducati have chosen the 90-degree V, which is better but by no means perfect, due to a strong horizontal force vector.

Now it appears that Yamaha has made the whole thing academic by using the vertical Twin configuration with a new twist. Counterbalancing.

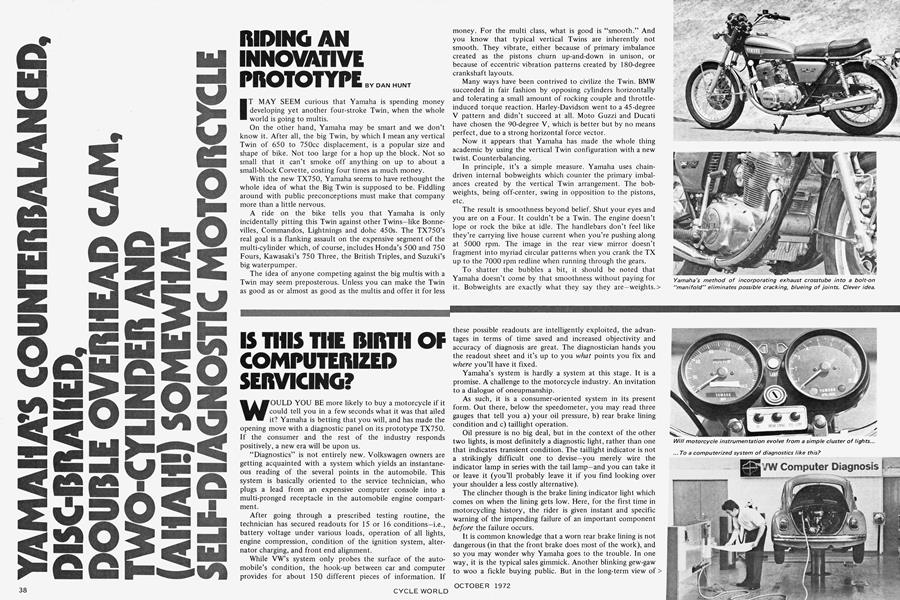

In principle, it’s a simple measure. Yamaha uses chaindriven internal bobweights which counter the primary imbalances created by the vertical Twin arrangement. The bobweights, being off-center, swing in opposition to the pistons, etc.

The result is smoothness beyond belief. Shut your eyes and you are on a Four. It couldn’t be a Twin. The engine doesn’t lope or rock the bike at idle. The handlebars don’t feel like they’re carrying live house current when you’re pushing along at 5000 rpm. The image in the rear view mirror doesn’t fragment into myriad circular patterns when you crank the TX up to the 7000 rpm redline when running through the gears.

To shatter the bubbles a bit, it should be noted that Yamaha doesn’t come by that smoothness without paying for it. Bobweights are exactly what they say they are—weights. The TX’s curb weight is 520 lb., which is even more th,an the Honda 750 Four (500 lb.) and only a few pounds less than the Suzuki Watercooled 750 (524 lb.).

The extra weight will tend to inhibit the performance of the TX750, which doesn’t have as impressive a power-toweight ratio as its predecessor, the SX-2. To compensate for this, Yamaha is playing with lower gearing than normal. Taking 7000 rpm as the upper limit, the particular machine we rode was geared for about 101 mph in 5th.

On the usual Twin, this high revving could create a great deal of discomfort at highway speeds, yet the counterbalanced Yamaha can get by quite nicely because the comfort factor isn’t dependent on the rpm at which the engine is turning. The overall ratios for public consumption have yet to be chosen, so keep in mind that the ones published in our data panel are only tentative and may be different on the showroom models.

Yamaha hopes to cash in with this smooth, heavy motorcycle by underselling the big multis, and offering a less bothersome package. As the bike is a Twin, it is somewhat easier to maintain than a Three or a Four. The TX750 has only two carburetors to balance, two spark plugs, two pistons and two sets of rings, fewer bearing surfaces, etc. The added complexity of the double overhead camshaft or the bobweight system will be a minor factor in respect to maintenance.

While Yamaha would have preferred to drive the double bobweights by gear, to avoid the adjustment schedule of chain drive, they found the gears too noisy in earlier prototypes. Switching to chain drive silenced the machine, from which emanates now the sporting sounds of whirring and clicking camshafts, noticeable but pleasant.

YAMAHA TX750

SPECIFICATIONS

The TX750 handles quite well for a machine of its weight. The frame is based on the excellent double cradle frame that houses Yamaha’s two-stroke 350 roadster and helps make it one of the best handling bikes you can buy. But even with the excellent frame, Yamaha must design excellent suspension to overcome the heavings created by 520 lb.

At the front end, they’ve done quite well with a set of double damping forks styled in the Ceriani tradition. At the rear, the rebound damping is inadequate and thus you feel slight amounts of unexpected wiggling over rough surfaces.

There is a trace of designed-in tendency to straighten when the bike is pitched hard into a short radius turn. It can be overcome well enough to move the bike around fast, and is not as noticeable in high-speed bends. It remains there as a safety factor for the novice rider—to prevent him from destroying a fifteen hundred dollar investment while rounding a 30 mph corner on the way to the drugstore. Some people won’t like this trait completely, but they only have to tolerate it at up to 40 mph or so.

The hydraulically actuated front disc brake is an absolute necessity on this machine and seems reasonably adequate for the 750’s weight and its intended usage. Its pads are double acting, which allows more rigid mounting of the calipers. In a

single-caliper disc brake assembly, the mounting arm must have a certain amount of give to allow the stationary brake puck to center itself with the rotation of the disc.

A double-acting puck system, being self-centering with a rigid mounting, helps prevent either puck from dragging on the disc and reduces feedback of any distortions or flaws in the disc itself. In certain instances, it may dampen all or part of the high frequency oscillations that cause disc brakes to squeal.

Yamaha apparently thinks that some TX750 riders will want even more brake than the present set-up provides, as the left fork leg has been provided with all the necessary protrusions and holes to mount a mirror image of the brake already there. So if you want the feeling that the hand of God has reached out to pull you down almost instantaneously, Yamaha has left you the option.

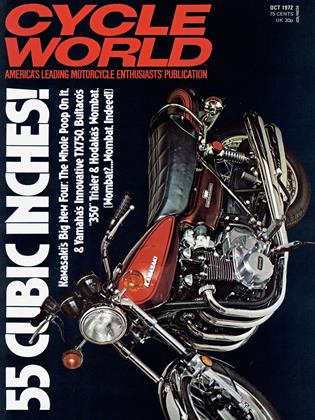

While all these mechanical niceties are appealing, and make for a fine machine for touring or freeway commuting, the most devastating innovation on Yamaha’s new bike may have to do with the little three-light idiot panel you can see next to the handlebars. It may seem like a gimmick, this panel which tells you about your oil pressure, taillight and brake lining condition, but it isn’t.

In effect, that panel opens a new era in motorcycling—the era of diagnostics. Much has been said about this new vehicular science, which promises a quick way to diagnose the source of many actual or potential mechanical ills. In a way, it is much more earthshaking than the fact that Yamaha has finally civilized the vertical Twin, so Yamaha’s “diagnostic panel” receives full treatment in the adjoining article.