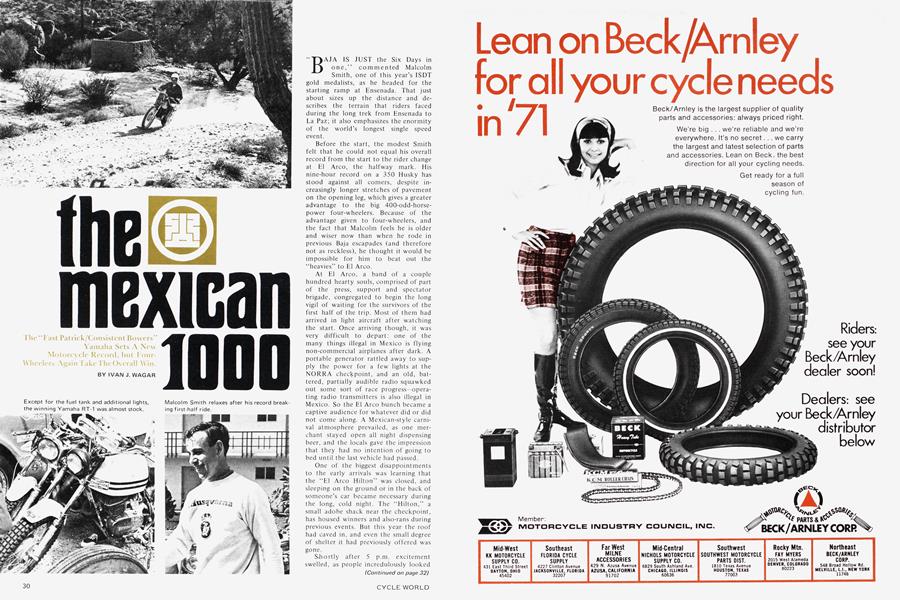

the mexican 1000

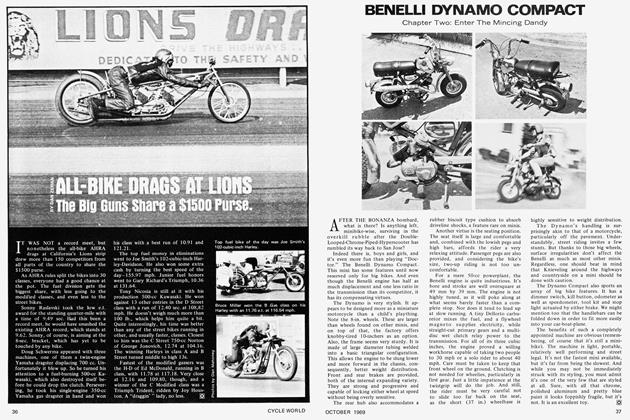

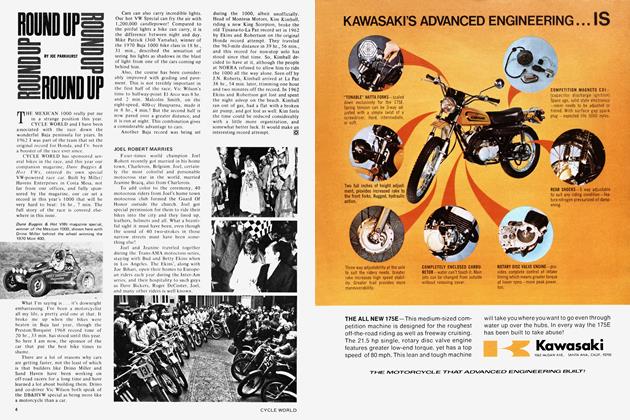

The“Fast Patrick/Consistent Bowers” Yamaha Sets A New Motorcycle Record, but FourWheelers Again Take The Overall Win.

IVAN J. WAGAR

BAJA IS JUST the Six Days in one,” commented Malcolm Smith, one of this year’s ISDT gold medalists, as he headed for the starting ramp at Ensenada. That just about sizes up the distance and describes the terrain that riders faced during the long trek from Ensenada to La Paz; it also emphasizes the enormity of the world’s longest single speed event.

Before the start, the modest Smith felt that he could not equal his overall record from the start to the rider change at El Arco, the halfway mark. His nine-hour record on a 350 Husky has stood against all comers, despite increasingly longer stretches of pavement on the opening leg, which gives a greater advantage to the big 400-odd-horsepower four-wheelers. Because of the advantage given to four-wheelers, and the fact that Malcolm feels he is older and wiser now than when he rode in previous Baja escapades (and therefore not as reckless), he thought it would be impossible for him to beat out the “heavies” to El Arco.

At El Arco, a band of a couple hundred hearty souls, comprised of part of the press, support and spectator brigade, congregated to begin the long vigil of waiting for the survivors of the first half of the trip. Most of them had arrived in light aircraft after watching the start. Once arriving though, it was very difficult to depart: one of the many things illegal in Mexico is flying non-commercial airplanes after dark. A portable generator rattled away to supply the power for a few lights at the NORRA checkpoint, and an old, battered, partially audible radio squawked out some sort of race progress—operating radio transmitters is also illegal in Mexico. So the El Arco bunch became a captive audience for whatever did or did not come along. A Mexican-style carnival atmosphere prevailed, as one merchant stayed open all night dispensing beer, and the locals gave the impression that they had no intention of going to bed until the last vehicle had passed.

One of the biggest disappointments to the early arrivals was learning that the “El Arco Hilton” was closed, and sleeping on the ground or in the back of someone’s car became necessary during the long, cold night. The “Hilton,” a small adobe shack near the checkpoint, has housed winners and also-rans during previous events. But this year the roof had caved in, and even the small degree of shelter it had previously offered was gone.

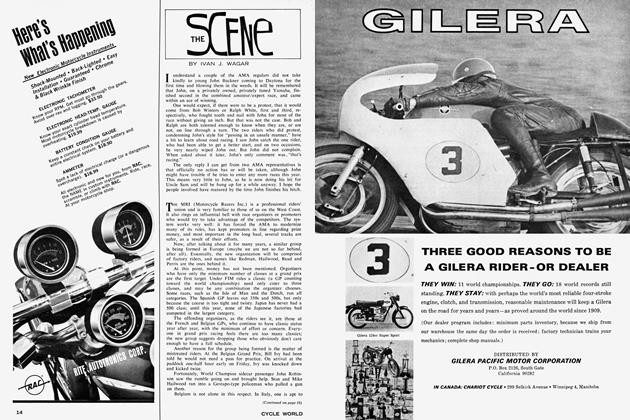

SJiortly after 5 p.m. excitement swelled, as people incredulously looked at their watches. In the distance there was the unmistakable rasp of a big Husqvarna, as Malcolm Smith motocrossed into El Arco in the unbelievable time of 8 hr., 4 min. Total excitement reigned among the motorcycle group until Vic Wilson rolled his VW-powered buggy in with an elapsed time two minutes better than Smith’s.

(Continued on page 32)

Continued from page 30

A few hours behind Smith came Kim Kimball, of Montesa Motors, looking almost too fatigued to continue. Kimball had requested that NORRA permit him to ride the event single-handed, but the association stuck by the rule book and insisted on a rider change at the half-way point. Undaunted, Kimball decided to start at Tijuana at midnight before the NORRA start and attempt to break the old solo record set by Dave Ekins. NORRA did agree to sell gas to Kimball at certain checks along the route.

After consuming all nine of his peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, and crashing three times, the indestructible Kimball completed the run in 38 hr., 54 min., a full hour and two minutes better than the old record. Despite the three skills, the almost standard King Scorpion looked little the worse for wear. Considering the fact that Kimball slept for a total of some five hours, the performance was an incredible feat.

Almost as surprising was the appearance at El Arco of Lew Buchanan. Lew, chief of the motorcycle division of the National Highway Safety Bureau, took over an entry at the last minute. An earlier radio report told us he was out with a broken carburetor on his l 25 Kawasaki. Somehow, with the aid of chewing gum, he was able to restart and arrive at El Arco near midnight, much to the surprise of his co-rider, who had sacked out for the night. The co-rider was no less than the director of NHSB, Doug Toms.

Buchanan had lost a half hour at Santa Ynes trying to repair a leaking tank, caused by a spill. So it was with a doubtful tank and an even more suspect carburetor repair that Toms left the meager shelter of El Arco to attempt the last half. These were not, however, the reasons for additional time losses, as Toms repaired three flat tires and stopped 16 times to clean plug whiskers caused by dirty gas at.the last check. Although the two “friendly feds” required 34 hr.. 15 min. to complete the run, they did make a bunch of friends among the Baja Brigade. There were a half-dozen good reasons for them to retire, but they plugged on with a determination that would make a mule envious. Through their efforts they also proved that it is becoming increasingly difficult for people in our industry to criticize “know nothing feds.”

(Continued on page 34)

Continued from page 32

The other Kawasaki 125, ridden by Don Graves and Alan Masek of Kawasaki, fulfilled the dream of the two desk-type executives, as they rolled home with a total time of 3 2 hr., 25 min. Hurd and Smith (DKW) took the 1 25-cc class in 21 hr., 35 min. This is the first year that motorcycles have been classified in more than one category, and the 125 class proved very popular. The competitiveness of the little machines can be judged by the fact that the DKW finished 5th among all bikes.

For the motorcyclists it was Mike Patrick who stole the show. His partner, the consistent Phil Bowers, lost time to Malcolm, but on the second leg Patrick opened the taps to pass Malcolm’s teammate Whitey Martino, who was temporarily sidelined with a broken rear chain. One of Mike's highlights was running out of gas almost within sight of La Paz. Seeing a group of young Mexican boys overhead on a bank, he ran up to check the fuel situation. They just happened to have an extra gallon in the trunk of the car and gladly turned it over to Mike. Knowing he was leading the race and grateful for the help, Patrick reached into his pocket and pushed a dollar bill into their hands, only to find out later it had been a 10 dollar bill. Patrick said that if he'd been anywhere but in the lead he would have gone back for change.

The winning Yamaha appeared very standard; the front forks, brakes and wheels were unchanged. A larger gas tank and two additional lights were fitted, but the remainder of the motorcycle seemed completely box-stock. The Gunnar Neilson/J.N. Roberts and the Smith/Martino Husqvarnas were 405-cc eight-speeders.

No less than seven four-wheelers beat the first motorcycle. The Wilson/Miller VW buggy finished first overall, more than two hours ahead of the first motorcycle. Wilson's little single-seater buggy, powered by a 2180-cc Volkswagen engine, is the product of almost endless development at Baja. Builder and codriver Drino Miller has come up with what is virtually a four-wheeled motorcycle.

It is almost certain to be a continuing trend that four-wheelers, such as Wilson’s, will better the finishing times of motorcycles, to win in overall record times. With the increased paving and grading that is done each year, the big cars and trucks are better able to utilize the 140-mph top speeds for longer periods of time.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

February 1971 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1971 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

February 1971 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

February 1971 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Special Preview Features

Special Preview FeaturesThe New Bsa/triumph 350

February 1971 By Dan Hunt -

Features

FeaturesMo-Ski-Tow

February 1971 By Gilles Mallet