The Good Old Winter Time

During The Twenties, The Slippery Season Offered Unique Opportunities

Gene Bizallion

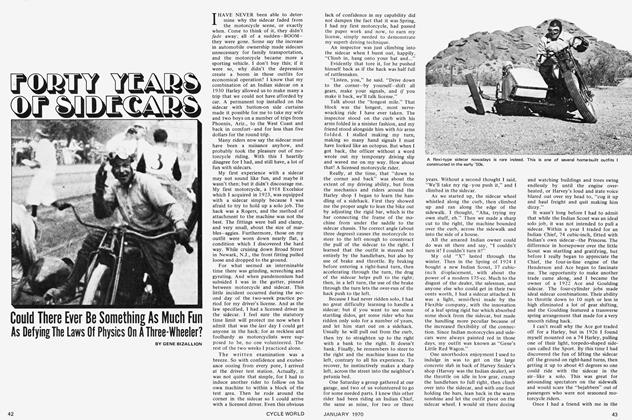

I WILL NOT MAINTAIN that winter was my favorite time of the year, but there came a choice of laying the motorcycle up 'til warm weather—which was inconceivable to me—or taking advantage of the unique opportunities offered by the slippery season. It occurs to me now, although I had reservations at the time, that I was fortunate in a way to spend years of motorcycle riding in an area of rather long, but not too severe, winters. In Newark, N.J., during the Twenties the temperature hovered somewhere around five above zero pretty consistently for four or five months. There was snow, eight inches to a foot deep, and the freezing period was long enough to furnish a substantial surface of ice on neighboring lakes.

And winter riding was not too uncomfortable once one donned the appropriate attire, which consisted of heavy underwear, a wool shirt, two pair of riding breeches, a layer of newspapers across the chest to check wind penetration, two sweaters, a three-quarterlength horsehide coat, high-lace boots over wool socks, and sometimes galoshes over the boots. For the head, a fleece-lined leather helmet and goggles with wide coverage to allow no gap between helmet and goggles across the forehead; a slight space here would let the cold wind start a knife-edge sensation which gradually created the impression that the top of the head was being sliced away. A protective scarf filled the space between the coat collar and the helmet, one end of which some of the Red Barons of the highway would leave streaming rakishly behind. Woolen gloves under leather thumb mitts could keep hands from freezing for several miles, and while handlebar windshields would be in the way in case of a spill, handlebar muffs were handy.

Occasional 100-mile runs were sponsored by various clubs, with emphasis on endurance. I usually favored the sidecar, but it developed that the sidecar chassis would bog down hopelessly in a foot or so of snow, while a solo job, with its small frontal area when equipped with chains on front and rear wheels, could plow through apparently impassable going. The chains were needed on front wheels to keep the wheels from clogging with snow and making like a runner. Wrestling a 74or 61-cu.-in. machine through a hundred miles of that travel constituted a good day's work.

We were coming down a mountain on one run, following what had once been a wood road but which had degenerated into a small creek flowing with ice churned up by the passage of riders ahead. A half dozen of us were in close, single file when we came to a dip forming a pool a couple feet deep. It was narrow enough that the front wheel would be climbing one side while the rear wheel was still on the other. Suddenly, those in front came to a halt, leaving Hiram Bogert in just that position, one wheel on each side of the pool, and no chance of reaching the ground with his feet. He could only topple over face down into the icy pool with his Harley landing across one leg, pinning him helplessly on his stomach. By raising himself on his arms, he was barely able to keep his chin above water.

We stopped, dismounted, and gathered about to appraise the situation cooly and calmly. It was quite evident from the fervor of irate bellows from the trapped one that some sort of action must be initiated. Not however, in frantic confusion, but with unruffled, constructive decision. One of the thoughtful group recalled a farmhouse some few miles back where we might borrow a rope or some sort of hoist to attach to a tree, and another, who had been a Boy Scout in his time, regretted he had left his hatchet home. With a hatchet we could surely have cut down a sapling and devised a lever to release the victim.

With no seeming appreciation for the tremendous amount of thought required for the rescue, Bogy's shouts became more vivid, verging on the indelicate, insinuating we would stand idly by while a fellow rider drowned in icy waters. It escapes me now what a superhuman effort brought about his release, possibly someone/merely lifted the Harley while a dripping, blasphemous Bogy crawled out. I do remember that most of us traveled on with the warm feeling of a good deed well done, while two volunteers remained to kindle a fire to dry the unfortunate one out.

I must mention here the adaptability of the motorcycles of that day to unforeseen emergencies of this nature. For starting in extremely cold weather, a small, syringe-like pump was included in the gas tank filler cap for the purpose of withdrawing a shot of gas to inject in priming cups in each cylinder. Likewise, by saturating any handy material with a squirt of gas, then removing a spark plug wire for a spark gap and kicking the engine over, fire could be created instantly.

But there were entertaining, and much less exacting, doings on the frozen lakes. Greenwood Lake, 40 miles north of Newark, would be covered with at least two feet of ice late in November, providing motorcycle and auto racing on the ice, along with sail and power ice boating, and skating. The big hotels around the lake stayed open during the ice season, bringing the lake alive with gyrations, especially over the weekends.

Over a period of years, motorcycle racing on the ice had developed into a well organized sport. The Greenwood Lake Racing Association had been formed so races could be run every week as closed club events, requiring no individual AMA sanctions. Qualifications for membership in the club were not too stringent, either: one must have a machine available for racing, possess $1 for the fee, and have only one thumb on his left hand. The engines used were the same fuel jobs ridden during the summer on the board tracks or on the hills—61-cu.-in. eight valves or 80-in. hillclimb engines mounted in light frames with a sidecar similar to the track flexis. Some had a torpedo-like body. Others mounted a simple platform on a sketchy chassis. On front and sidecar wheels were mounted ribbed racing tires with Mj-in.-sq. steel bar stock bent and welded into hoops cornerwise. The corners were ground to a sharp edge, and located between the ribs of the tires. Sometimes the front wheel might not begin turning for a quarter of a mile, but the steel edge gave steering control like a runner.

For traction, five or six loops of motorcycle drive chain were placed around the rear tires, fastened with connecting links and put on before the tires were aired up so the air pressure pulled them up solid. Surprisingly, these chains withstood speeds up to 110 miles an hour. Time trials were run over the measured mile, wired for an electric timer, but straightaway races with six or moj"e riders through three or five miles, using a mile flying start, furnished a bit of direct competition.

My sole venture into this action came as a passenger on a sidecar which consisted of nothing more than a board bolted directly to the chassis, and I lay on my stomach gripping the chassis tubes. It might not have been too bad if we had been out in front, but we dove into the race from the rolling start at the usual 100-mile speed, and fell into 4th position. The clouds of ice churned up by the outfits ahead totally obscured everything for me, and I doubted if the driver could see any more. My goggles became plastered with ice and, having no extra hands to wipe them, I just hung on, anticipating that my head would be rammed into someone's spinning rear wheel with skid chains, or that one of those chain links would come loose and go right through me lengthwise.

This activity, I decided, might be interesting enough for the spectators, but limited in scope for participants. So, I preferred mainly to cruise about the lake with my sidehack seeking whatever diversion might appear. Such as the time two girls on skates hailed me for a tow from the upper end of the lake down to the racing area. One of them hooked her elbows over the back of the sidecar and the other hung onto the first one's coat tails. I kept sneaking the speed up as much as traction would allow. We were moving a good 50 miles an hour when the girl clinging to the coat tails tripped and went down. The fall was of no consequence since she was so swaddled in coats, but the surface of the lake was a little unusual that day. Snow had blown out on the ice and frozen lightly in islands here and there, about a foot deep and 20 feet or so across. This gal was really cruising, flat on her stomach and no brakes. She hit a snow patch and disappeared therein with a terrific burst of spray. I pulled off to one side and followed along to watch her come out the other side like a projectile, trailing snow like the tail of a comet, zip across a clear space, and plunge head first into the next patch.

I accompanied the wild slide for more than a quarter-mile as she slammed through the drifts and flashed across the clearings; it was a sight to behold. Finally she lost momentum and slid to a stop. I rode over to offer my congratulations on the performance, but she just lay there in silence gesturing frantically toward her mouth, and then I saw it was still wide open packed full of snow. Well, you'd have laughed too, if you'd been there.

Her friend, who had still clung to the sidecar, helped me get her on her feet and skate her over to the hack like a statue, and load her in. As we drove more sedately down to the racing area, the girl on the back started reciting a soliloquy covering me and my ancestors for generations back until the one in the sidecar got her mouth unplugged, then they took turns consigning me to regions where there would be no frozen lakes, and neither repeated the same word twice.

Sail ice boats, capable of tacking across wind at 80 and 90 miles an hour, swarmed about the lake. Skaters flitted thither and yon by the hundreds, and several of the motorcycle enthusiasts had built ice boats driven by motorcycle engines with propellers. Some of these were as fast as any of the sailboats.

Design know-how was acquired the hard way. The first of these powerboats followed sailboat practice with two runners in front, steered by a tiller on one runner in back. Immediately it developed that without a stabilizing sail, driving one of these rigs was similar to steering an automobile in reverse at 80 miles an hour, winding up inevitably in a long, drawn out gillhooly with the passengers hanging on for dear life. The satisfactory setup proved to be two runners in front and two in back. The front two connected with a tie rod to steer like an automobile. Due possibly to the lack of a National Safety Committee, no guards were placed over the propellers, and I always marveled that some unfortunate skater was never sliced into salami cold cuts.

Charley Busch's boat featured a Harley 74 hung inverted to lower the center of gravity, and all constituted authorities promised the engine would not function inverted. But the only modification required was a hole drilled from the top of the timing gear case (which was then the lower side) into the crankcase for oil drainage to the inside of the pistons, which served as a sump. Other builders came up with varied designs powered with Cleveland and Henderson four-cylinder engines.

There was also the genius who located a large rocking chair and brought it up to the lake. With the chair and occupant on a hundred feet of rope behind a sidehack with light skid chains, we would get moving up to 60 miles an hour or better, then start a long, slow turn. This would swing the chair out to one side until it was sliding sideways almost even with the towing outfit; another long turn in the other direction would whip the chair across in an arc at amazing velocity. Then eventually it came to pass. With the chair in full arc, tilted back on the tips of the rockers, the rope stretched until it hummed like a fiddle string, with the passenger holding himself in with arms locked under the chair arms. Then, the arms pulled out of the chair while the back was at an ideal angle for a launching ramp. The passenger rose gracefully in a lofty trajectory like Zuccini the Human Cannonball. From a brief glimpse of the expression on his face, I gathered he was anticipating the termination of the flight with some concern.

However, this amusement was shortlived, for in the next run down the lake with the chair out in a magnificent broadslide, and Van Houten clinging desperately to the replaced arms, a block of ice left frozen on the surface by some fisherman put the quietus on this piece of equipment for good. The chair rockers hit the ice block, and the whole thing disintegrated into a bundle of kindling wood, while Van made the ice smoke as he took off for the far side of the lake flat on his back.

Surprisingly, there were no real tragic accidents on the ice, but a few mangled sidecars and bent forks were a foregone conclusion. One of these tangles led me indirectly into an incident proving that even endeavors of almost childlike innocence could produce results closely approaching disaster. Van Houten was a mechanic at the Harley shop, and one Monday morning he was dispatched to the lake to bring a Harley sidehack with crumpled forks back for repairs. I elected to go along for the ride.

We took the shop's double-width sidecar fitted with a wide, shallow box, and I was hunched up with my back to the front against a bitter winter wind, my horsehide coat up around my neck, and helmet snugged over my ears. Casting about for a diversion from the chilling monotony, I spied several coils of rope tied in the sidecar. With the thought that here might be as innocuous a pastime as one could imagine, I unwound one coil and let it drag along the road behind us. I then tied more coils together until there was about 300 feet of rope slithering in back.

I was congratulating myself that here was an activity which might not be completely understood, but at least it should cause me no complications, when an impending catastrophe stared me in the face. We were rounding a long curve and I was watching with fascination the rope far down the highway swinging out across the shoulder of the road, mowing down all growth thereon with a devastating efficiency, when we passed a group of people standing by the roadside waiting for a bus. A quick analysis told me that unless I could achieve a lightning-like evasive action, we would, with equal efficiency, yank out the underpinnings from a number of prospective bus passengers. Fortunately, these folks were momentarily interested in some sort of activity in a bordering field and took no notice of a passing motorcycle or a rope gliding along the highway. I managed to haul in enough rope so that only a few feet flipped across the feet of a woman standing in the foreground.

The effect was simply amazing. Without visible effort she rose a foot in the air and screamed. One of those fullthroated, piercing shrieks that can shatter nerves and turn the blood to ice water. It rang in my ears above the noise of our passage, even through my helmet, and thoroughly panicked a treefull of birds by the roadside, evidently bringing to a conclusion their indecision concerning a belated trip south. The volume must have been horribly unhinging at close range, for the dignified gentleman beside her, leaning nonchalantly on his cane, executed several involuntary, Saint Vitus-like steps of a Spanish fandango. Van heard the screech and glanced back, but I motioned him on, for without consultation, I knew he would agree we would be ill advised to return with an explanation.

So maybe it wasn't entirely "the good old winter time," but it had its points and I wouldn't have missed it. There would have been too much of life wasted. In the warmth of the shop in back of Carl Bush's Harley agency, the recollection of some of those little episodes would help while away the time until the lilacs bloomed again and the odor of burning grass and warming asphalt promised that the "Spring Opening Run" would offer a whole new calendar of fantastic possibilities.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

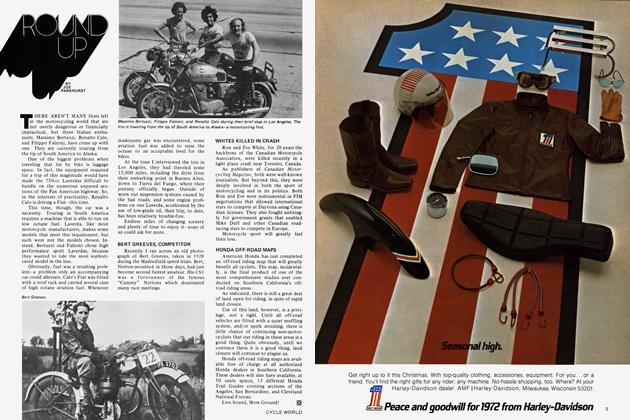

DepartmentsRound Up

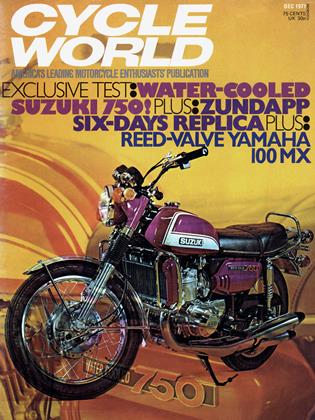

DECEMBER 1971 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

DECEMBER 1971 -

Departments

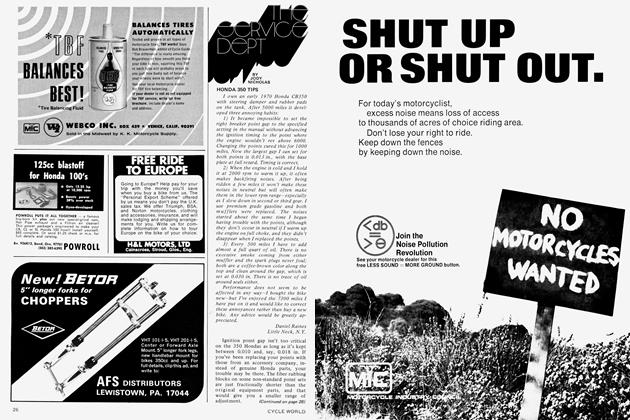

DepartmentsThe Service Dept

DECEMBER 1971 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

DECEMBER 1971 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Features

FeaturesViewpoint: the Road Bike In Tomorrow's World

DECEMBER 1971 By Dan Hunt -

Competition

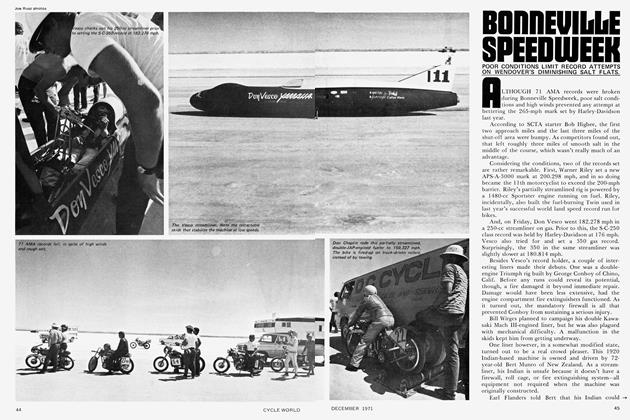

CompetitionBonneville Speedweek

DECEMBER 1971