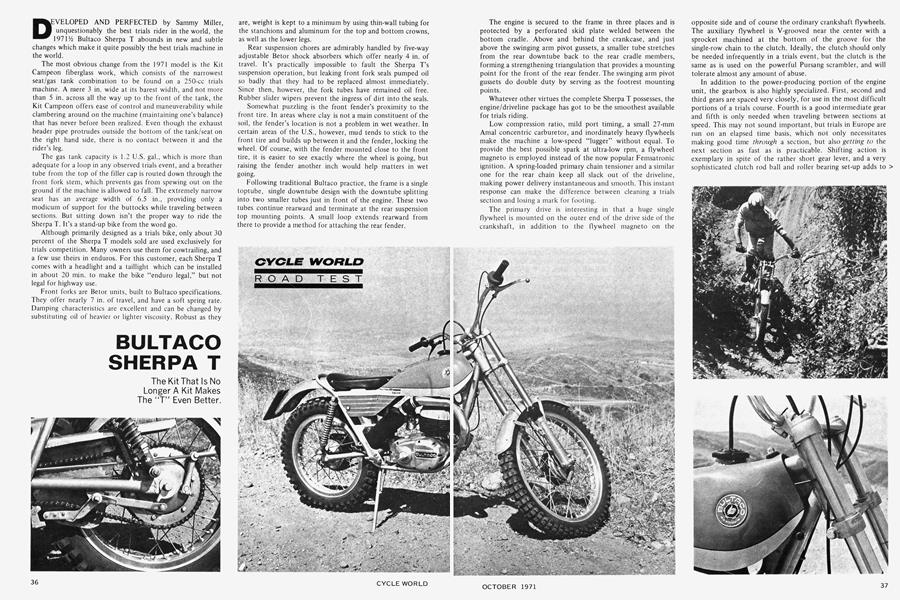

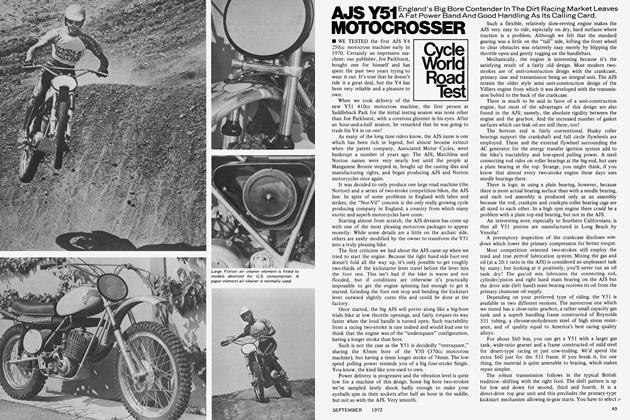

BULTACO SHERPA T

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

The Kit That Is No Longer A Kit Makes The "T" Even Better.

DEVELOPED AND PERFECTED by Sammy Miller, unquestionably the best trials rider in the world, the 1971½ Bultaco Sherpa T abounds in new and subtle changes which make it quite possibly the best trials machine in the world.

The most obvious change from the 1971 model is the Kit Campeon fiberglass work, which consists of the narrowest seat/gas tank combination to be found on a 250-cc trials machine. A mere 3 in. wide at its barest width, and not more than 5 in. across all the way up to the front of the tank, the Kit Campeon offers ease of control and maneuverability while clambering around on the machine (maintaining one’s balance) that has never before been realized. Even though the exhaust header pipe protrudes outside the bottom of the tank/seat on the right hand side, there is no contact between it and the rider’s leg.

The gas tank capacity is 1.2 U.S. gal., which is more than adequate for a loop in any observed trials event, and a breather tube from the top of the filler cap is routed down through the front fork stem, which prevents gas from spewing out on the ground if the machine is allowed to fall. The extremely narrow seat has an average width of 6.5 in., providing only a modicum of support for the buttocks while traveling between sections. But sitting down isn’t the proper way to ride the Sherpa T. It’s a stand-up bike from the word go.

Although primarily designed as a trials bike, only about 30 percent of the Sherpa T models sold are used exclusively for trials competition. Many owners use them for cowtrailing, and a few use theirs in enduros. For this customer, each Sherpa T comes with a headlight and a taillight which can be installed in about 20 min. to make the bike “enduro legal,” but not legal for highway use.

Front forks are Betor units, built to Bultaco specifications. They offer nearly 7 in. of travel, and have a soft spring rate. Damping characteristics are excellent and can be changed by substituting oil of heavier or lighter viscosity. Robust as they are, weight is kept to a minimum by using thin-wall tubing for the stanchions and aluminum for the top and bottom crowns, as well as the lower legs.

Rear suspension chores are admirably handled by five-way adjustable Betor shock absorbers which offer nearly 4 in. of travel. It’s practically impossible to fault the Sherpa T’s suspension operation, but leaking front fork seals pumped oil so badly that they had to be replaced almost immediately. Since then, however, the fork tubes have remained oil free. Rubber slider wipers prevent the ingress of dirt into the seals.

Somewhat puzzling is the front fender’s proximity to the front tire. In areas where clay is not a main constituent of the soil, the fender’s location is not a problem in wet weather. In certain areas of the U.S., however, mud tends to stick to the front tire and builds up between it and the fender, locking the wheel. Of course, with the fender mounted close to the front tire, it is easier to see exactly where the wheel is going, but raising the fender another inch would help matters in wet going.

Following traditional Bultaco practice, the frame is a single toptube, single downtube design with the downtube splitting into two smaller tubes just in front of the engine. These two tubes continue rearward and terminate at the rear suspension top mounting points. A small loop extends rearward from there to provide a method for attaching the rear fender.

The engine is secured to the frame in three places and is protected by a perforated skid plate welded between the bottom cradle. Above and behind the crankcase, and just above the swinging arm pivot gussets, a smaller tube stretches from the rear down tube back to the rear cradle members, forming a strengthening triangulation that provides a mounting point for the front of the rear fender. The swinging arm pivot gussets do double duty by serving as the footrest mounting points.

Whatever other virtues the complete Sherpa T possesses, the engine/driveline package has got to be the smoothest available for trials riding.

Low compression ratio, mild port timing, a small 27-mm Amal concentric carburetor, and inordinately heavy flywheels make the machine a low-speed “lugger” without equal. To provide the best possible spark at ultra-low rpm, a flywheel magneto is employed instead of the now popular Femsatronic ignition. A spring-loaded primary chain tensioner and a similar one for the rear chain keep all slack out of the driveline, making power delivery instantaneous and smooth. This instant response can make the difference between cleaning a trials section and losing a mark for footing.

The primary drive is interesting in that a huge single flywheel is mounted on the outer end of the drive side of the crankshaft, in addition to the flywheel magneto on the opposite side and of course the ordinary crankshaft flywheels. The auxiliary flywheel is V-grooved near the center with a sprocket machined at the bottom of the groove for the single-row chain to the clutch. Ideally, the clutch should only be needed infrequently in a trials event, but the clutch is the same as is used on the powerful Pursang scrambler, and will tolerate almost any amount of abuse.

In addition to the power-producing portion of the engine unit, the gearbox is also highly specialized. First, second and third gears are spaced very closely, for use in the most difficult portions of a trials course. Fourth is a good intermediate gear and fifth is only needed when traveling between sections at speed. This may not sound important, but trials in Europe are run on an elapsed time basis, which not only necessitates making good time through a section, but also getting to the next section as fast as is practicable. Shifting action is exemplary in spite of the rather short gear lever, and a very sophisticated clutch rod ball and roller bearing set-up adds to

the smoothness and reliability of the unit.

The tiny front brake and normal rear brake provide more than enough stopping power for trials riding, and are less apt to get wet because of longer sealing lips and more careful machining on the brake backing plates. Thick, strong spokes connect the hubs with Akront alloy rims which are somewhat lighter, and allegedly stronger, than steel rims. In typical trials fashion, the rear tire is a 4.00-18 and the front is a 3.00-21. Not so typically trials is the tread pattern: knobby! Each factory distributor has the option of tire tread patterns, and Bultaco services orders their Sherpa T models with knobbies.

This may seem curious, as Trials Universals are considered the usual tread for observed trials. In Europe and Great Britain, the universal tread is required by FIM rules. However, the situation is different in the U.S.; most trials clubs here allow use of the knobby pattern, except in certain areas (notably Southern California, where the universal is required). And not forgetting how many trials bike owners do not ride trials, it is small wonder that the distributor opts for knobby tires.

BULTACO SHERPA T

$895

Location of the motorcycle’s controls is conventional for a trials machine with flat, wide handlebars, a low seating position and high footpegs. The rear brake pedal is interesting in that it pivots from inside the frame tubes, which helps prevent breakage in rocky terrain. The actual point of contact between it and the rider’s left boot is circular in shape, hollow to prevent the build-up of mud, and features sharp, saw-toothing on top for better grip. The footpegs are spring-loaded and similarly saw-toothed.

The gear lever on the right side is sufficiently far away from the footpeg to prevent snicking the transmission into a neutral inadvertantly while negotiating a tricky section. Clutch and brake levers are adjustable steel items, which seems strange in view of the apparent effort to save a few ounces by the use of an aluminum alloy transmission drain plug. Why not use aluminum levers instead?

The 1969 Sherpa T test weighed in at 219 lb. wet, whereas the 197F/4 Kit Campeón tips the scales at 212 lb., the lightest 250 trials bike available. Finish and quality of construction have come up considerably in the past few years. Although a couple of the frame tubes are a little rough, the assembly’s welding is very good indeed and little touches here and there are pleasing. Some of the little touches are annoying too; for example, the muffler’s “stinger” should have been made round instead of tapered, and angled slightly outward to facilitate the installation of a spark arrestor. Now, the exhaust blows onto the speedometer cable, cooking the insulation off, and sprays an oily mist onto the rear hub. All the fender mount bolts and those three which attach the seat/tank unit should have elastic stop-nuts as standard equipment. It is also necessary to re-torque the top fork nuts to 150 lb.-ft. to assure proper seating of the fork tubes, and there are other little things that need to be done to make the machine 100-percent reliable. Of course, any bike designed for dirt riding should be thoroughly inspected and adjusted before it is ridden seriously.

In spite of some small criticisms, the Kit Campeón Sherpa T is the finest 250 trials machine presently available. [o]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue