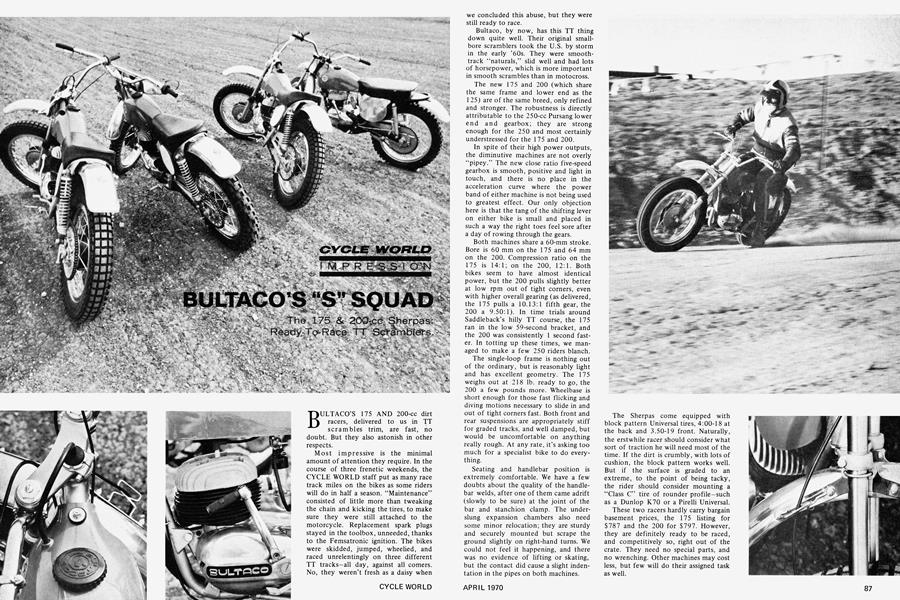

BULTACO'S "S" SQUAD

CYCLE WORLD IMPRESSION

The 175 & 200-cc Sherpas Ready-To-Race TT Scrambters.

BULTACO'S 175 AND 200-cc dirt racers, delivered to us in TT scrambles trim, are fast, no doubt. But they also astonish in other respects.

Most impressive is the minimal amount of attention they require. In the course of three frenetic weekends, the CYCLE WORLD staff put as many race track miles on the bikes as some riders will do in half a season. "Maintenance" consisted of little more than tweaking the chain and kicking the tires, to make sure they were still attached to the motorcycle. Replacement spark plugs stayed in the toolbox, unneeded, thanks to the Femsatronic ignition. The bikes were skidded, jumped, wheelied, and raced unrelentingly on three different TT tracks-all day, against all corners. No, they weren't fresh as a daisy when we concluded this abuse, but they were still ready to race.

Bultaco, by now, has this TT thing down quite well. Their original smallbore scramblers took the U.S. by storm in the early '60s. They were smoothtrack "naturals," slid well and had lots of horsepower, which is more important in smooth scrambles than in motocross.

The new 175 and 200 (which share the same frame and lower end as the 1 25) are of the same breed, only refined and stronger. The robustness is directly attributable to the 250-cc Pursang lower end and gearbox; they are strong enough for the 250 and most certainly understressed for the 175 and 200.

In spite of their high power outputs, the diminutive machines are not overly "pipey." The new close ratio five-speed gearbox is smooth, positive and light in touch, and there is no place in the acceleration curve where the power band of either machine is not being used to greatest effect. Our only objection here is that the tang of the shifting lever on either bike is small and placed in such a way the right toes feel sore after a day of rowing through the gears.

Both machines share a 60-mm stroke. Bore is 60 mm on the 175 and 64 mm on the 200. Compression ratio on the 175 is 14:1; on the 200, 12:1. Both bikes seem to have almost identical power, but the 200 pulls slightly better at low rpm out of tight corners, even with higher overall gearing (as delivered, the 175 pulls a 10.13:1 fifth gear, the 200 a 9.50:1). In time trials around Saddleback's hilly TT course, the 175 ran in the low 59-second bracket, and the 200 was consistently 1 second faster. In totting up these times, we managed to make a few 250 riders blanch.

The single-loop frame is nothing out of the ordinary, but is reasonably light and has excellent geometry. The 175 weighs out at 218 lb. ready to go, the 200 a few pounds more. Wheelbase is short enough for those fast flicking and diving motions necessary to slide in and out of tight corners fast. Both front and rear suspensions are appropriately stiff for graded tracks, and well damped, but would be uncomfortable on anything really rough. At any rate, it's asking too much for a specialist bike to do everything.

Seating and handlebar position is extremely comfortable. We have a few doubts about the quality of the handlebar welds, after one of them came adrift (slowly to be sure) at the joint of the bar and stanchion clamp. The underslung expansion chambers also need some minor relocation; they are sturdy and securely mounted but scrape the ground slightly on right-hand turns. We could not feel it happening, and there was no evidence of lifting or skating, but the contact did cause a slight indentation in the pipes on both machines.

The Sherpas come equipped with block pattern Universal tires, 4:00-18 at the back and 3.50-19 front. Naturally, the erstwhile racer should consider what sort of traction he will need most of the time. If the dirt is crumbly, with lots of cushion, the block pattern works well. But if the surface is graded to an extreme, to the point of being tacky, the rider should consider mounting a "Class C" tire of rounder profile—such as a Dunlop K70 or a Pirelli Universal.

These two racers hardly carry bargain basement prices, the 175 listing for $787 and the 200 for $797. However, they are definitely ready to be raced, and competitively so, right out of the crate. They need no special parts, and no wrenching. Other machines may cost less, but few will do their assigned task as well.

LITTLE BIKES are becoming quite I sophisticated nowadays. They display refinements and engineer-

ing never thought practicable just a few years ago. As it was, if a guy wanted to go dirt racing in the lightweight classes, his choice of competitive machinery was meager indeed. And all too often he ended up with a tatty, second-hand hybrid of dubious history and even more dubious reliability.

But those days of slim pickin's are fading, and none too rapidly at that. The market demands good lightweight racers and is willing to pay for them. And while these new Bultaco purebreds aren't the first production motocrossers of this size, they are among the most competitive ever offered the consumer.

Although our two test machines ap pear quite similar at first glance, we discovered several substantial differ ences between them. Of these the most prominent is frame configuration. The 100 sports a scaled down frame based on Pursang proportions; two top tubes and two rear down tubes. The 125 uses a standard Sherpa frame, featuring single top and down tubes and a longer wheelbase (51.8 in. vs. 53.5 in.)

Ihe larger Sherpa frame was likely assigned to the 125 powerplant because of its greater horsepower (22 bhp at 9000 rpm), while the 16 bhp of the smaller engine remains within the lighter frame's design limits.

Also, the 1 25 was fitted with a massive front fork which is, in effect, a shortened 360 Bandido unit. Inside the fork all diameters are to Bandido specs, stanchions included. Bear in mind that this fork was designed for a machine weighing 50 lb. more than the 125. And with such a beefy assembly on the front end of this lightweight, overstre~ing or bending should prove well nigh impos sible. Needless to say, no bottoming occurred even though it was subjected to some dreadful pounding in the test.

The softly sprung 100 with a smaller fork scored equally well in this area.

When we put both machines on the scales we were surprised to note that the 125 weighed 27 lb. more than its 1 90-lb. little brother. The suspected reason for this difference is the substi tution of those heavier chassis compo nents.

This is not to imply, the 125 is overweight. weight ratio is actually 100's: each bhp of the compared to the 100's 1 however, that Its power-to better than the 125 pulls 9.8 lb. 1.8 lb./bhp.

Both bikes handle very well for their intended purpose and are bags of fun on a motocross circuit. But the 100 seems to have a slight edge in responsiveness due to its lesser weight and shorter wheelbase. It steers more precisely and handles bumps and dips with a bit more insouciance.

Because the bikes were set up with 21-in, front wheels it was comparatively easy to aviate the front end over obsta cles and surface irregularities. Further more, the behavior of both machines over a series of rapid one-foot hoop-de doos was remarkably stable with no tail-wagging or unexpected lurches.

Braking also was very good. Smooth ness and predictability of slowing are highly prized virtues among motocross bikes and these Bultacos are well up to the challenge. Sudden locking and rear wheel hop were nonexistent as both front and rear brakes provided just enough feedback for precise and even control. This, combined with the ma chines' light weight, allows the rider to plunge deep into a turn with what appears to be wanton abandon.

Horsepower of the 100 is competitive and above average. While we've ridden a few more powerful 100s, the little Bul will get the nod for its flexibility. And on a motocross course sheer horsepower is a liability to all but expert riders. On the other hand, though, the 100 is hardly a slogger and one must use the five-speed gearbox to stay on the power band.

The same can also be said of the 125, which is best described as being moder ately peaky but not excessively so, considering its displacement and power output. It is a fast, high strung little racer that begs you to keep the gas on and the gears stirred. In terms of horsepower, this bike will run with any other 125 motocrosser made. To boot, its handling is very good if not the best we've encountered in this displacement category.

The 100 & 125-cc Sherpas: Swift, Stable Motocrossers.

But of all the noted virtues of these two bikes the most valuable must be their long term reliability. They are definitely over-engineered and as such are almost indestructible. Both powerplants incorporate the exact same transmission that is used on the 250-cc Bultacos. If you weigh the torque capacity of this rugged unit against the power delivered by each of these engines, you'll see that even under the most maniacal abuse the transmission is nowhere near its limits.

The same line of thought has been carried into the engine also. The 125 uses the same 60-mm stroke crankshaft assembly that spins in the 250s. So you can see why we are impressed with it; to all intents and purposes the engine is a sleeved down 250; only the 51.5-mm bore is different.

The 100 lower end has also received much the same treatment. For although it has a smaller stroke (49.5 mm), bearings and journal sizes are the same as those on the 250.

Undoubtedly, ideas of swapping your 100-cc parts for big bore barrels and pistons dance in your mind—if everything else is the same, why not use 175, 200 or 250 parts? Well, unfortunately the larger pieces don't fit due to the shorter stroke. This is not such a good idea anyway, as the increased power in a short wheelbase chassis would make for a rather skittery mount.

However, the 125 engine will accept the other parts with no hassle. And because its frame is identical with that used on the 175-200 Sherpa series, there is no danger of putting too much strain on engine mounts, etc. Nor would it be necessary to implement chassis modifications, as wheelbase, shocks and incidentals are all the same too.

It doesn't take a clairvoyant to tell that these new machines will be a great success in lightweight Sportsman racing. With its zingy horsepower and excellent handling the 100 will surely score big in competition. And while its suggested retail price of $654 may seem a bit steep for a 100-cc motorcycle, one musn't forget the excellent quality of components and engineering involved.

The same can be said of the $749 125-cc Sherpa. And like the 100 it has all the prerequisites to win: a space age Femsatronic ignition, alloy wheels and fenders, a grisly determination, and most importantly, excellent manners on a motocross track.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

April 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

April 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

April 1970 By John Dunn -

Features

FeaturesA Mind of Its Own

April 1970 By Bob Ebeling -

A Cycle World Exclusive

A Cycle World ExclusiveWhat Does Suzuki Have Up Its Sleeve?

April 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar