THE HENDEE SPECIAL

A 1914 PUHBUTTON PIONEER

GEOFF HOCKLEY

WITH AN OUTPUT of more than 35,000 machines for the year 1913, the Hendee Mfg. Co. of Springfield, Mass., makers of America's oldest motorcycle, the Indian, clinched its claim to be the world's largest producer of motorcycles.

Its two chief competitors, HarleyDavidson of Milwaukee and Excelsior of Chicago, had also exceeded all their previous production figures, for these were the palmy days of American motorcycling, with the motorcycle widely accepted for transport and pleasure—a happy state of affairs which unfortunately gradually waned until, 30 years later, motorcycling was at a very low ebb indeed. (Now the wheel has turned full circle once more, and motorcycling in America is booming more than at any time in its history.) But in 1913 the outlook for the industry was bright, and Indian, with more than 2000 dealers throughout the country and in foreign lands, and branches in many cities overseas, was perhaps the brightest star in the motorcycle firmament.

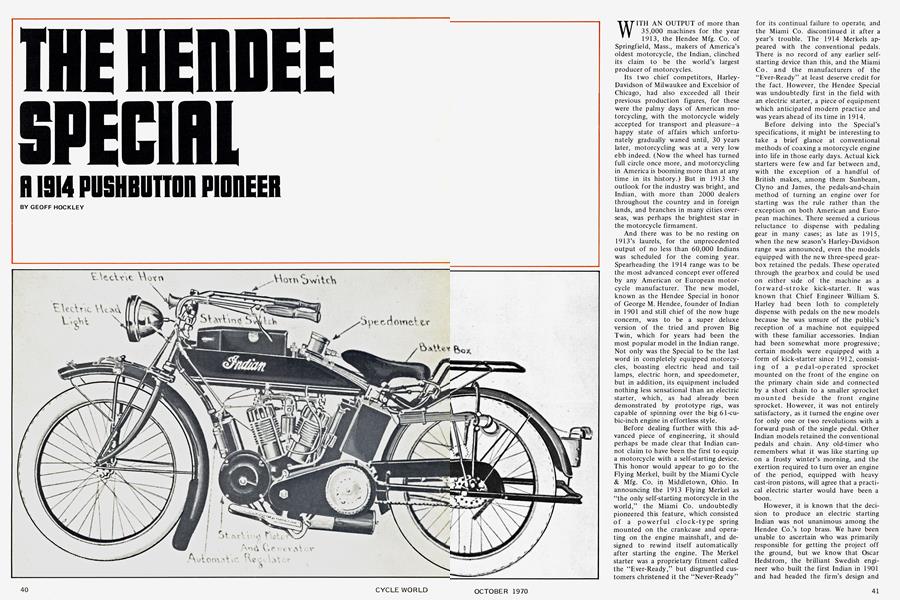

And there was to be no resting on 1913’s laurels, for the unprecedented output of no less than 60,000 Indians was scheduled for the coming year. Spearheading the 1914 range was to be the most advanced concept ever offered by any American or European motorcycle manufacturer. The new model, known as the Hendee Special in honor of George M. Hendee, founder of Indian in 1901 and still chief of the now huge concern, was to be a super deluxe version of the tried and proven Big Twin, which for years had been the most popular model in the Indian range. Not only was the Special to be the last word in completely equipped motorcycles, boasting electric head and tail lamps, electric horn, and speedometer, but in addition, its equipment included nothing less sensational than an electric starter, which, as had already been demonstrated by prototype rigs, was capable of spinning over the big 61-cubic-inch engine in effortless style.

Before dealing further with this advanced piece of engineering, it should perhaps be made clear that Indian cannot claim to have been the first to equip a motorcycle with a self-starting device. This honor would appear to go to the Flying Merkel, built by the Miami Cycle & Mfg. Co. in Middletown, Ohio. In announcing the 1913 Flying Merkel as “the only self-starting motorcycle in the world,” the Miami Co. undoubtedly pioneered this feature, which consisted of a powerful clock-type spring mounted on the crankcase and operating on the engine mainshaft, and designed to rewind itself automatically after starting the engine. The Merkel starter was a proprietary fitment called the “Ever-Ready,” but disgruntled customers christened it the “Never-Ready” for its continual failure to operate, and the Miami Co. discontinued it after a year’s trouble. The 1914 Merkels appeared with the conventional pedals. There is no record of any earlier selfstarting device than this, and the Miami Co. and the manufacturers of the “Ever-Ready” at least deserve credit for the fact. However, the Hendee Special was undoubtedly first in the field with an electric starter, a piece of equipment which anticipated modern practice and was years ahead of its time in 1914.

Before delving into the Special’s specifications, it might be interesting to take a brief glance at conventional methods of coaxing a motorcycle engine into life in those early days. Actual kick starters were few and far between and, with the exception of a handful of British makes, among them Sunbeam, Clyno and James, the pedals-and-chain method of turning an engine over for starting was the rule rather than the exception on both American and European machines. There seemed a curious reluctance to dispense with pedaling gear in many cases; as late as 1915, when the new season’s Harley-Davidson range was announced, even the models equipped with the new three-speed gearbox retained the pedals. These operated through the gearbox and could be used on either side of the machine as a forward-stroke kick-starter. It was known that Chief Engineer William S. Harley had been loth to completely dispense with pedals on the new models because he was unsure of the public’s reception of a machine not equipped with these familiar accessories. Indian had been somewhat more progressive; certain models were equipped with a form of kick-starter since 1912, consisting of a pedal-operated sprocket mounted on the front of the engine on the primary chain side and connected by a short chain to a smaller sprocket mounted beside the front engine sprocket. However, it was not entirely satisfactory, as it turned the engine over for only one or two revolutions with a forward push of the single pedal. Other Indian models retained the conventional pedals and chain. Any old-timer who remembers what it was like starting up on a frosty winter’s morning, and the exertion required to turn over an engine of the period, equipped with heavy cast-iron pistons, will agree that a practical electric starter would have been a boon.

However, it is known that the decision to produce an electric starting Indian was not unanimous among the Hendee Co.’s top brass. We have been unable to ascertain who was primarily responsible for getting the project off the ground, but we know that Oscar Hedstrom, the brilliant Swedish engineer who built the first Indian in 1901 and had headed the firm’s design and engineering department since then, was opposed to the project and refused to be associated with it-a decision which, coming from a genius of Hedstrom’s caliber, must have caused some slight misgivings among the electric-starter proponents. But the pessimists were overruled and the project was gotten under way.

The robust starter-generator unit was attached to the front engine mounting plates by two lugs. An internal commutator carried inside the armature member was used, the brushes being supported by the cover plate and projecting into the interior of the armature to make contact with the commutator segments. The armature shaft was mounted on large single-row journal bearings. This method of construction kept the width of the unit down to moderate dimensions and it protruded little more than a couple of inches from the engine crankcase. Being inside the inner edge of the footboard, it was moderately well protected in the event that the machine fell over. The unit was connected to the engine by sprockets and chain, the gearing being approximately 2:1, and it was claimed that the system would crank the engine at 500 rpm, considerably faster than the average automobile starter of the period. Under normal operating conditions it could be expected to start a cold engine in 12 to 15 sec., while a warm engine would start almost instantaneously. The nominal rating of the combined starter and generator was 1.5 hp, but the power actually developed was influenced by the energy necessary to start the engine.

A switch box mounted on the front of the tank-mounted toolbox directed the current from two 6V batteries contained in a case mounted on the seat post tube to the starting motor fields when the switch was placed in the “start” position. When the engine started, the operator moved the switch to the “running” position, altering the circuits so that the generator current was supplied to the batteries via a cut-out and voltage regulator which maintained the charging rate in accordance with the state of the batteries. This latter item is surely indicative of the progressive thinking of Indian’s design staff at this period, in that they anticipated modern practice by 20 years or more. In fact, voltage regulators (Lucas) first made their appearance on British machines about 1937. Coil ignition was used, the coils being mounted in front of the engine on the downtube of the frame, with the cut-out and voltage regulator alongside them.

Any doubts that the Special would prove one of the biggest sensations of the motorcycle world were dispelled as the new model went on display at Indian dealers throughout the world. Curious crowds, including many members of the non-motorcycling public, thronged dealers’ salesrooms where the Special was being demonstrated and watched fascinated as it started at the touch of a switch. Across the Atlantic, crowds jammed the Hendee Co.’s London branch in Euston Road to see the new model being demonstrated by London manager W.H. “Billy” Wells and his staff.

A contemporary report states after a day’s continuous stop-and-start demonstration the batteries “became weakened” and were replaced. However, after many hours of being drained by starting operations without running the engine long enough to charge them, the batteries would understandably show signs of distress, bearing in mind that the battery of 55 years ago could not be remotely compared with its present-day counterpart. But all in all, the Special clearly demonstrated that a practical electric starting system for motorcycles wasn’t a pipe dream, but had actually arrived.

However, after the shouting and the tumult had died and the Special had become something less than a nine-days wonder, doubts began to insinuate themselves in the minds of Indian dealers and the factory “brass” as to whether the new model wasn’t, perhaps, a trifle ahead of its time for the average buyer. Dealers reported a very definite “wait and see” attitude among prospects, many of whom seemed overawed at the elaborateness of the “electrics” after the spartan equipment they had been accustomed to for so long. The general feeling was that it would be prudent to let the other fellow buy one first (the Special’s price tag, incidentally, was $325). The path of pioneers and innovators has ever been difficult and stony, and there was no exception in the case of the Special.

Another grave obstacle in getting the new model successfully under way was the average dealer’s ignorance, or inexperience, in servicing electrical equipment. This was hardly to be wondered at, considering the fact that electric starters on automobiles had been introduced only two or three years before and were still found only on a few expensive makes. It was not surprising, therefore, that the average motorcycle mechanic felt somewhat flabbergasted when confronted with a trouble-shooting job on the Special. And troubles there were, too, though most of them seemed to have been caused by riders and dealers being unfamiliar with the electrical equipment. The batteries were the Special’s Achilles heel, for these vital items were unknown 55 years ago and, in addition, were subjected to severe stresses, not only in carrying out the job for which they had been designed, but also in standing up to jolts and shocks if the machines were used on

the notoriously poor country roads of that period, which must have considerably lessened their life. The coil ignition system also did not enhance the Special’s popularity. The dependable magneto had been standard for years, and riders looked askance at the complication of the Special’s ignition system, pondering lengthily on the chances of being stranded with flat batteries miles from a service station. While touching on this aspect of the Special, here’s an interesting item which appeared during the research on this model. In an English motorcycle magazine containing an announcement of the Special there was an illustration of the new model. It was magneto equipped. Could it be that the canny British distributors mistrusted the Special’s coil ignition system and ordered the new models magneto equipped? It is quite possible that the distributors considered that the conservative British buyer might shy away from coil ignition. Had the Indian factory equipped the Special with magneto ignition from its inception, thus eliminating the serious objection of being unable to start if the batteries were flat, the machine would probably have survived for longer than it did, for it had disappeared from the range when the 1915 models were announced.

This, then, was the world’s first electric-starting motorcycle—an ambitious and progressive concept which deserved a better fate but failed, hot because of any inherent defects in design or construction, but mainly because it was too far advanced for its day. To the best of my knowledge, not a single Special is in existence today. A pity, for an example of this once-famous model would be honored as testimony to the progressive thinking of an American manufacturer more than 55 years ago.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Department

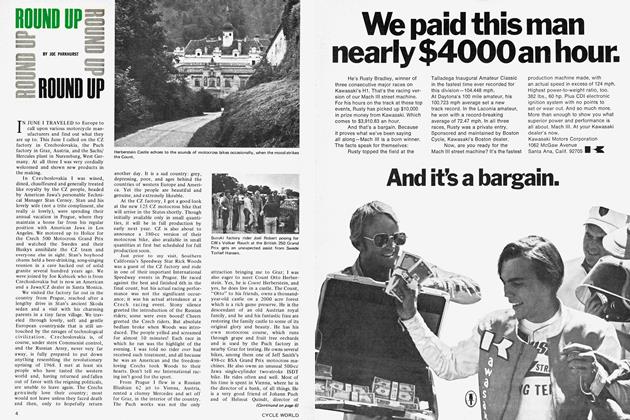

DepartmentRound Up

October 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

October 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Special Technical Feature

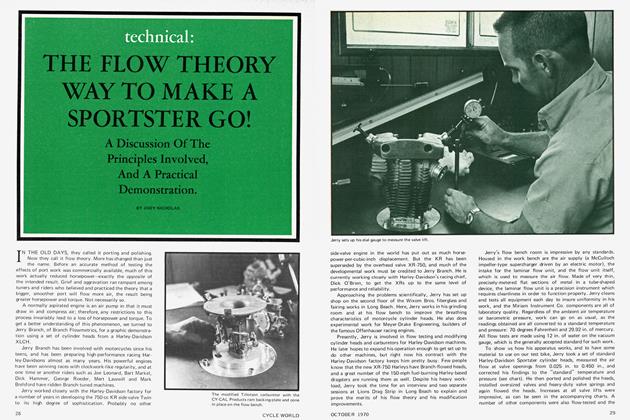

Special Technical FeatureTechnical: the Flow Theory Way To Make A Sportster Go!

October 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Features

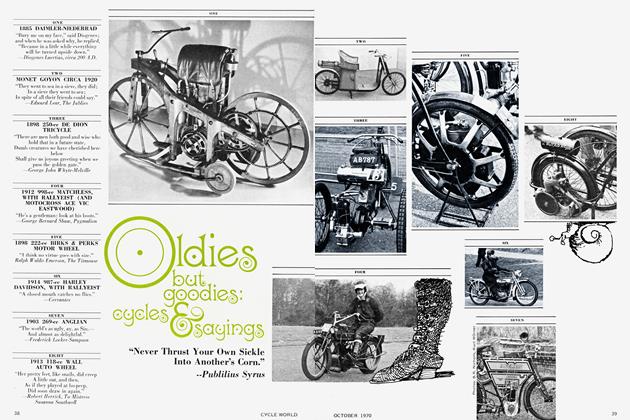

FeaturesOldies But Goodies: Cycles & Sayings

October 1970 By Publilius Syrus -

Competition

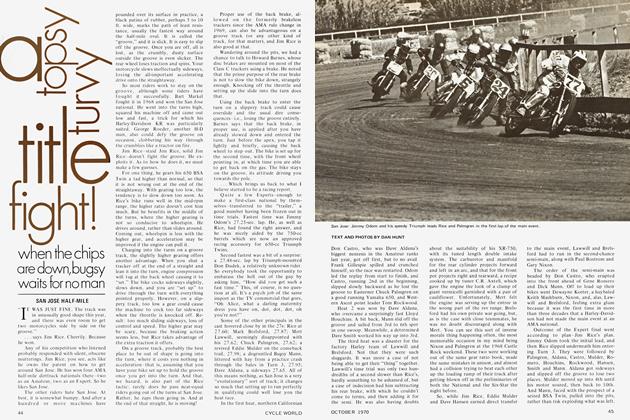

CompetitionA Topsy Turvy Title Fight!

October 1970 By San Jose Half-Mile