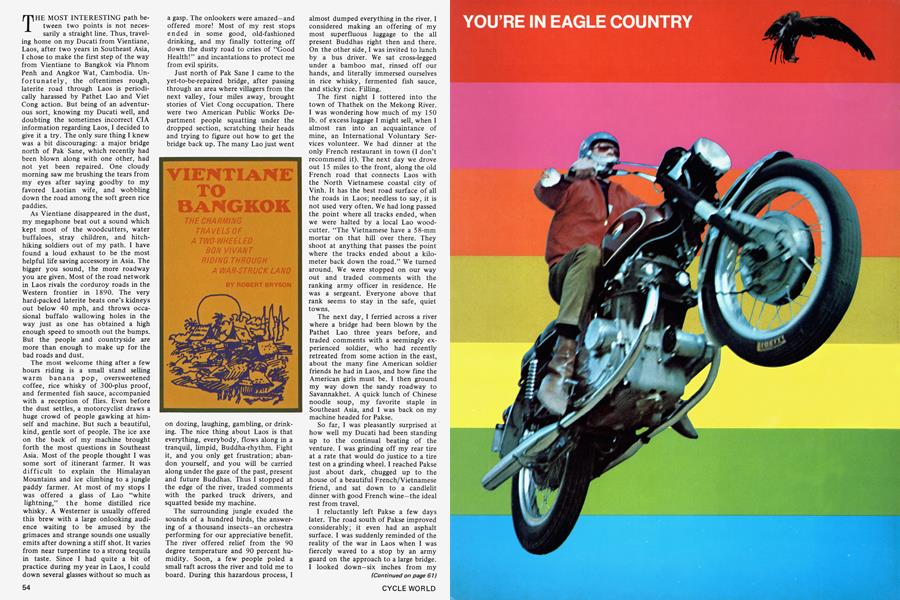

VIENTIANE TO BANGKOK

THE CHARMING TRAVELS OF A TWO-WHEELED BON VIVANT RIDING THROUGH A WAR-STRUCK LAND

ROBERT BRYSON

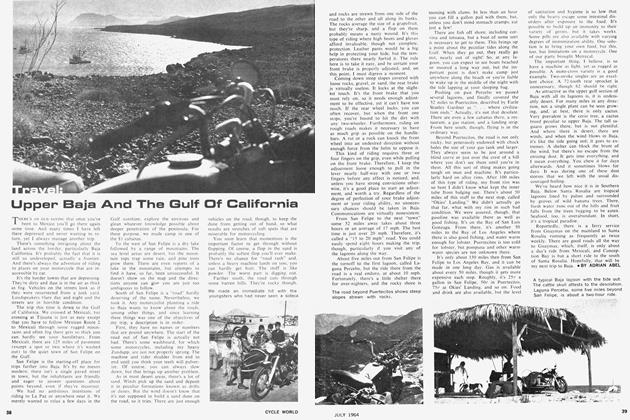

THE MOST INTERESTING path between two points is not necessarily a straight line. Thus, traveling home on my Ducati from Vientiane, Laos, after two years in Southeast Asia, I chose to make the first step of the way from Vientiane to Bangkok via Phnom Penh and Angkor Wat, Cambodia. Unfortunately, the oftentimes rough, latente road through Laos is periodically harassed by Pathet Lao and Viet Cong action. But being of an adventurous sort, knowing my Ducati well, and doubting the sometimes incorrect CIA information regarding Laos, I decided to give it a try. The only sure thing I knew was a bit discouraging: a major bridge north of Pak Sane, which recently had been blown along with one other, had not yet been repaired. One cloudy morning saw me brushing the tears from my eyes after saying goodby to my favored Laotian wife, and wobbling down the road among the soft green rice paddies.

As Vientiane disappeared in the dust, my megaphone beat out a sound which kept most of the woodcutters, water buffaloes, stray children, and hitchhiking soldiers out of my path. I have found a loud exhaust to be the most helpful life saving accessory in Asia. The bigger you sound, the more roadway you are given. Most of the road network in Laos rivals the corduroy roads in the Western frontier in 1890. The very hard-packed latente beats one’s kidneys out below 40 mph, and throws occasional buffalo wallowing holes in the way just as one has obtained a high enough speed to smooth out the bumps. But the people and countryside are more than enough to make up for the bad roads and dust.

The most welcome thing after a few hours riding is a small stand selling warm banana pop, oversweetened coffee, rice whisky of 300-plus proof, and fermented fish sauce, accompanied with a reception of flies. Even before the dust settles, a motorcyclist draws a huge crowd of people gawking at himself and machine. But such a beautiful, kind, gentle sort of people. The ice axe on the back of my machine brought forth the most questions in Southeast Asia. Most of the people thought I was some sort of itinerant farmer. It was difficult to explain the Himalayan Mountains and ice climbing to a jungle paddy farmer. At most of my stops I was offered a glass of Lao “white lightning,” the home distilled rice whisky. A Westerner is usually offered this brew with a large onlooking audience waiting to be amused by the grimaces and strange sounds one usually emits after downing a stiff shot. It varies from near turpentine to a strong tequila in taste. Since I had quite a bit of practice during my year in Laos, I could down several glasses without so much as a gasp. The onlookers were amazed—and offered more! Most of my rest stops ended in some good, old-fashioned drinking, and my finally tottering off down the dusty road to cries of “Good Health!” and incantations to protect me from evil spirits.

Just north of Pak Sane I came to the yet-to-be-repaired bridge, after passing through an area where villagers from the next valley, four miles away, brought stories of Viet Cong occupation. There were two American Public Works Department people squatting under the dropped section, scratching their heads and trying to figure out how to get the bridge back up. The many Lao just went on dozing, laughing, gambling, or drinking. The nice thing about Laos is that everything, everybody, flows along in a tranquil, limpid, Buddha-rhythm. Fight it, and you only get frustration; abandon yourself, and you will be carried along under the gaze of the past, present and future Buddhas. Thus I stopped at the edge of the river, traded comments with the parked truck drivers, and squatted beside my machine.

The surrounding jungle exuded the sounds of a hundred birds, the answering of a thousand insects—an orchestra performing for our appreciative benefit. The river offered relief from the 90 degree temperature and 90 percent humidity. Soon, a few people poled a small raft across the river and told me to board. During this hazardous process, I almost dumped everything in the river. I considered making an offering of my most superfluous luggage to the all present Buddhas right then and there. On the other side, I was invited to lunch by a bus driver. We sat cross-legged under a bamboo mat, rinsed off our hands, and literally immersed ourselves in rice whisky, fermented fish sauce, and sticky rice. Filling.

The first night I tottered into the town of Thathek on the Mekong River. I was wondering how much of my 150 lb. of excess luggage I might sell, when I almost ran into an acquaintance of mine, an International Voluntary Services volunteer. We had dinner at the only French restaurant in town (I don’t recommend it). The next day we drove out 15 miles to -the front, along the old French road that connects Laos with the North Vietnamese coastal city of Vinh. It has the best road surface of all the roads in Laos; needless to say, it is not used very often. We had long passed the point where all tracks ended, when we were halted by a local Lao woodcutter. “The Vietnamese have a 58-mm mortar on that hill over there. They shoot at anything that passes the point where the tracks ended about a kilometer back down the road.” We turned around. We were stopped on our way out and traded comments with the ranking army officer in residence. He was a sergeant. Everyone above that rank seems to stay in the safe, quiet towns.

The next day, I ferried across a river where a bridge had been blown by the Pathet Lao three years before, and traded comments with a seemingly experienced soldier, who had recently retreated from some action in the east, about the many fine American soldier friends he had in Laos, and how fine the American girls must be. I then ground my way down the sandy roadway to Savannakhet. A quick lunch of Chinese noodle soup, my favorite staple in Southeast Asia, and I was back on my machine headed for Pakse.

So far, I was pleasantly surprised at how well my Ducati had been standing up to the continual beating of the venture. I was grinding off my rear tire at a rate that would do justice to a tire test on a grinding wheel. I reached Pakse just about dark, chugged up to the house of a beautiful French/Vietnamese friend, and sat down to a candlelit dinner with good French wine—the ideal rest from travel.

I reluctantly left Pakse a few days later. The road south of Pakse improved considerably; it even had an asphalt surface. I was suddenly reminded of the reality of the war in Laos when I was fiercely waved to a stop by an army guard on the approach to a large bridge. I looked down—six inches from my front wheel was a trip wire for a mine that the Royal Lao Army in the south uses to deter the Pathet Lao from crossing bridges at night. It was still too early in the morning for the Lao army to begin functioning. So I waited.

(Continued on page 61)

Continued from page 54

The next day I continued south, stopping briefly at the immense Rhone Falls, a place where the Mekong takes a drop of about 150 feet. I considered the possibility of hydroelectric power, and what the Mekong River Basin might look like in perhaps 50 years, if the Mekong River Project is ever completed. Arriving at the Lao border checkpoint of Karnak, I had to search around for half an hour before I could find someone to stamp my passport. I’m still not sure if he was the right person, as he was somewhat unsure of what to do with my passport, and marked it with the incorrect stamp anyway.

The span between Karnak and Dorn Kralor, Cambodia, is virtually a 20-mile stretch of no-man’s-land. I’ve talked to hitchhikers who have almost perished there because of the lack of population and the almost complete lack of traffic between Laos and Cambodia. The Cambodians at the customs checkpoint had the audacity to charge me $5 for a temporary import permit for my machine. I demanded an official receipt and left them grumbling over a one dollar bill. I continued southward over good roads and through beautiful green jungle. Near Strang Treng I had to wait three hours for the ferry, which was out of diesel fuel. It seemed there were no funds in the local treasury to buy any. Finally the ferry chugged to the landing, and, as we crossed the river, an Asian sunset tinted the brown waters a lurid red.

That night I came to the Cambodian equivalent of a truck stop. Good food, and a nice clean, cool shower—Asian style. It also happened that the Vietnamese owner, an old widow, spoke Lao. We stayed up half the night exchanging stories on Vietnam, Laos and good people. The truck drivers came roaring in about midnight in their Cambodian converted Dodges. The place was really jumping.

Once in Cambodia, there always were people crowding around my machine, asking where it was made and how many cc. They were amazed at the 180-mph speedometer and the obtrusive, legible, red-lined tachometer. Cambodian motorcyclists are restricted to Jawas. The Cambodian government has nationalized the import business, and Jawa is one of the few machines above 100 cc admitted. I soon learned why after buying my first Cambodian gasoline near Kratie. Even with a retarded timing of about 5 degrees after tdc, my poor machine (with a 10:1 compression ratio) would not even run in fifth gear

on the stuff. It was about 30 percent No. 3 diesel fuel, 30 percent gasoline, and 30 percent rice water. After Kratie, the surroundings became rubber plantations once established by the French and now nationalized by the Cambodian government. After the “company town” of Snoul, I made a small excursion down a rough, rocky road which would have taken me to the Vietnamese border in 30 miles and, eventually, to Loc Ninh. The rubber tappers I met a few miles down the road warned me that it was an “action” area. They also explained that the beautifully maintained airstrip a few hundred yards down the road was used frequently by the Americans to land ahead of fleeing Viet Cong units, trying to trap them between two forces.

The remaining journey to Phnom Penh was mostly good road, friendly people, and a free ferry passage, as the fare taker was a latent motorcyclist himself. There, I looked up the brother of a companion of mine in Vientiane, who had to leave Cambodia as he was involved in smuggling, and the police were after him. We retired to one of the many French type cafes and discussed motorcycles over a glass of Pernod. Phnom Penh is a very French, and a very pleasant Southeast Asian city, but perhaps overly quiet. I stayed approximately four days in the very luxurious, but economical Hotal Royal, mostly around the swimming pool, talking to the many French women who were there on vacation, and also stewardesses.

The next morning I fired up the noisy Ducati and retraced part of my route north before turning to Kampong Cham, the road which would take me to the Thai border via Siem Reap and Angkor Wat. There was a strong, but not cold rain most of that day, but I enjoyed burbling along. The rain, loud exhaust and laughing children created an elixir that carried me all the way to Siem Reap in one day. Siem Reap is the town where the famous Mon-Khmer ruins of Angkor Wat are located. That evening I drove farther out to another of the ruins of the Angkor Wat complex, Banteay Strei, and spent the evening camped in the 10th Century pink sandstone miniature monument to Shiva.

The Angkor Wat complex of ruins deserves a note of compliment. The whole area, at least 45 square miles, is a series of temples begun about 800 AD and evacuated about 1100 by the early Mon-Khmer of Cambodia. The ruins of these immense temples are scattered through a very lovely, lush jungle, which smelled of jasmine and orchids. The natives are mostly unconcerned and unaware of the financial rewards of tourism; those who cater to travelers are very helpful. The two main roads which encircle and meander through the ruins make the area perfect for motorcycling. I became enchanted with this site on antiquity. Wandering through the ruins under a full moon, I kept expecting to see a young Cambodian maiden of times past on a distant rampart, a fragrant orchid in her hair, dancing in the moonlight.

I had been warned in Phnom Penh that the border between Cambodia and Thailand was occasionally closed, as Thailand and Cambodia have a border dispute going, along with Sihanouk’s neutrality and Thailand’s close ties to the United States in Vietnam. The Cambodians at the border checkpoint of Poipet were very friendly, quickly processed my papers, and escorted me to a large, iron gate in the middle of a bridge over a small creek, which formed the border. The gate, secured by a medieval lock weighing at least 50 lb., squeaked open and rattled shut behind me. A few hundred yards down the road I clunked into the Thai checkpoint of Aranyaprathet. The officials there were surprised to see a Thai-speaking “Farang” come from Cambodia on a motorcycle.

The remaining afternoon drive to Bangkok consisted of the worst and the best roads I had encountered since leaving Vientiane. There was a 50-mile stretch of road that was being rebuilt, and it began to rain. Try driving in foot-deep mud with a motorcycle with clip-ons and 150 lb. of baggage. Wheel I used all of the 50-ft. width as I slid my way onto a new four-lane parkway leading to Bangkok. I found the safest way of driving in Thailand is to turn your lights on—all the time. Otherwise, any bus, truck or car that gets the chance will pass, or try to, approaching traffic, and force you off the road in the process. The outlook in Thailand is that anything with two wheels should be driven on the shoulder of the road, which is a bit difficult at 60 mph. Lights on means that you are determined, aggressive, and be damned if you will move! It works. That evening saw me fighting the rush-hour traffic of Bangkok, blinded by the bar and massage parlor lights on New Phetburi Road and dreaming of a small, bamboo hut in a Lao village.

I had covered over 1500 miles of road and my Ducati had stood up amazingly well for the thrashing it had received. Nevertheless, the next day I headed for my friendly Ducati dealer in Bangkok and contemplated the next leg of the trip from Bangkok to Katamandu via Singapore.