THE SCENE

IVAN J. WAGAR

IT is getting near that time of year when the American Motorcycle Association has an annual meeting to decide the rules and policies for the next competition year. This will be the second meeting of the Competition Congress, which consists of some 60 members from all branches of our sport and industry. Although an AMA company member, CYCLE WORLD is not a member of the Congress, nor does it have a voice. This probably is the way it should be, because we can think of many things wrong with the way in which the AMA operates.

Because we do not have a voice, it sometimes is necessary to use this column so that Congress members may understand our thinking, and will perhaps present our views at the meeting. The AMA now has a professional motocross category and, according to many Congress members, it came about mainly because of the strenuous efforts of this column last year.

This year we have two points of major concern. The first item is one which has been given considerable space in the past: the indiscriminate suspension of riders who compete in nonAM A-sanctioned races. One case in point is the Dick Mann affair. Dick is National No. 2, and one of the greatest supporters and backers the AMA has ever had. He was suspended for riding in the Inter-Am motocross at Pepperell, Mass., last year on a weekend when the AMA did not have a professional race of any sort in the whole of the United States.

The second example involves Gordon Jennings, a motorcycle journalist and unsupported privateer who rides nothing but road races, and, at great expense, supported every AMA road race last year. All three of them! But he committed a cardinal sin. He entered an AAMRR road race at Indianapolis. There was no AMA road race that weekend, and, as our friend put it, “I would have driven another thousand miles for an AMA road race, but there wasn’t one.”

Logic would have it that neither Mann, nor Jennings, “hurt” the AMA by their actions. So why should the AMA hurt them? But political theorists have long recognized that governing bodies rarely operate on the same rules that govern individual behavior.

Would you believe that there still are people in the AMA who refer to any non-AMA race as an “outlaw event,” and to non-AMA clubs as “outlaw groups.” But who really are the good guys?

If we really are to believe the AMA is for the betterment of our sport, the Congress must make it impossible for some nut to put down one of our National number riders. After all, the AMA is stronger in California than in any other state, despite the fact that the AMA cannot suspend riders for competing in any non-AMA event in the state of California because of the Cartwright Act. Here is an example where the AMA prospered through the existence of non-AMA organizations. And, except for Gary Nixon, almost every AMA road race star has gained experience outside of AMA events.

It seems that no one in the AMA has been smart enough to realize that if the organization cannot supply a form of motorcycle sport to satisfy competitors and the public, another group will be formed to satisfy the demand. If the group succeeds in promoting worthwhile events, much good will come of the whole thing. Riders and the general public will start going to events, dealers will sell machines and parts, the riders will become more proficient, and as they do they will use more parts. Then the dealer becomes more prosperous, moves to a better location, joins the Lions Club and becomes more respected in his community. Suddenly, because of some “outlaw club” our industry is better off than before.

The punch line in this whole chain of events is: when the AMA does get off its butt and offers events of a like nature, the riders will join the AMA and race, and the already developed race audience will continue to roll through the turnstiles, dropping those bucks.

The excuse which the AMA hired help use for handing out suspensions is rider loyalty. The home office must be certain that AMA riders will go to an AMA event, and not some Mickey Mouse meet down the road. But suspension encourages bitterness, not loyalty. All the AMA has to do to maintain rider loyalty is to put on a real race, with real money, and tender just a little respect for the riders. Then rider loyalty will be coming out of their ears.

The FIM has a good system to ensure rider loyalty: if a rider enters an event, and does not show up on race day, his license is pulled. The whole business is left pretty much up the race promoter and the strength of his objections. If the rider is a big name, and his appearance has been advertised, he’d better have a good excuse for not showing. If the race organizers are satisfied with the excuse, they probably will not report the rider to the governing body. In the case of a lesser known rider whose name had not been used in pre-race advertising, there is a good chance that nothing whatever would come of it. The same thinking could apply to the AMA. If, for instance, in negotiations with a prospective promoter, the AMA said it would guarantee the top 20 riders, plus a number of lesser ranked riders, then anyone in the top 20 had better have a good reason if he misses the event. This, plain and simple, is grounds for suspension; harm has been done to the association. But for the AMA to take a rider’s license for no good reason is petty stupidity. In Dick Mann’s case, it meant he could not race in a series of indoor short track races during the off season, and that is bread and butter to a professional rider.

I think, too, that it is the duty of the Competition Congress to force the AMA Executive Committee to hire people in the head office who like motorcycles. When I attend many AMA races, it makes me sick to see so many executives and officials really down on the riders, mechanics, press and just anyone there doing a job.

It has to be much more enjoyable to go to an SCTA trials, an AFM road race or an ACA motocross. The money is not so good, but everyone is there because they like motorcycle competition. There must be many capable and willing people who like motorcycles, and want to make a good salary as a full time employee of the largest motorcycle race sanctioning body.

The second item of concern is the hodgepodge of race distances, and related rulings. Some progress has been made; all half-mile dirt track Nationals are now 20 laps. But the road races are something else!

The AMA requires a mandatory pit stop for any road race of more than 100 miles. This is fine for something like the Daytona 200. But what about Indy, the 110-mile National? You have to have a pit stop at Indy, because it is more than 100 miles. But what real difference is there between Indy and the Loudon 100-mile National, where no pit stop is required? Why indeed should Indy be 110 miles? Surely the number, 110, draws no more spectators than the number, 100.

As it is at Indy, all the fiddling with token pit stops is something to see. And it plays havoc with the lap scoring.

Thus I would like to see all road races, with the exception of the big ones like Daytona, run 100 miles (or less). And, while uniformity is not so necessary on the dirt tracks, it would be good, from the spectator interest point of view, to limit mile track races to a distance of 20 or 25 miles.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

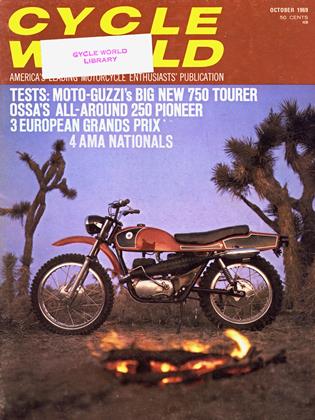

OCTOBER 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

OCTOBER 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

OCTOBER 1969 -

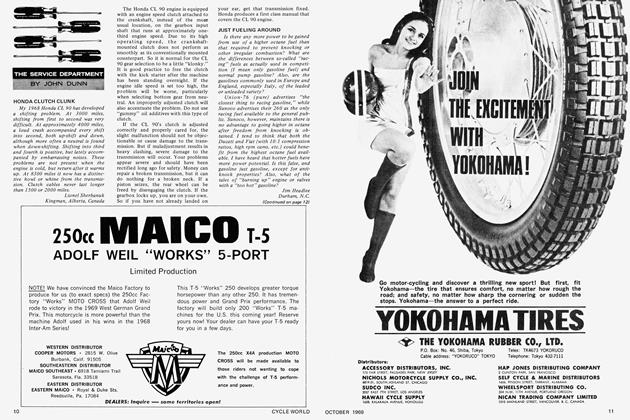

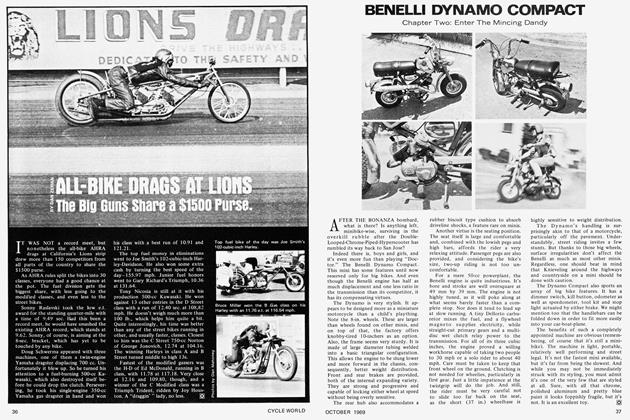

Competition

CompetitionAll-Bike Drags At Lions the Big Guns Share A $1500 Purse.

OCTOBER 1969 By Dan Zeman -

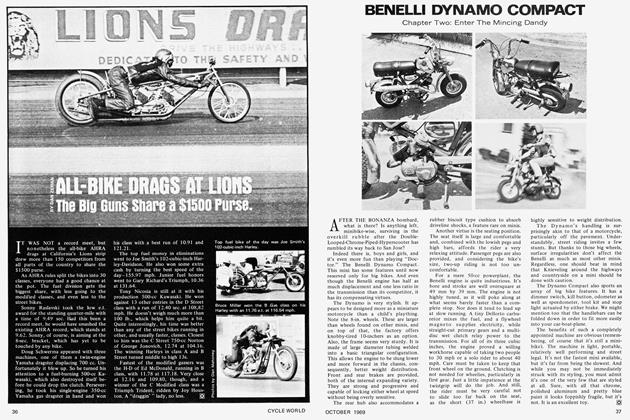

Tests

TestsBenelli Dynamo Compact

OCTOBER 1969 -

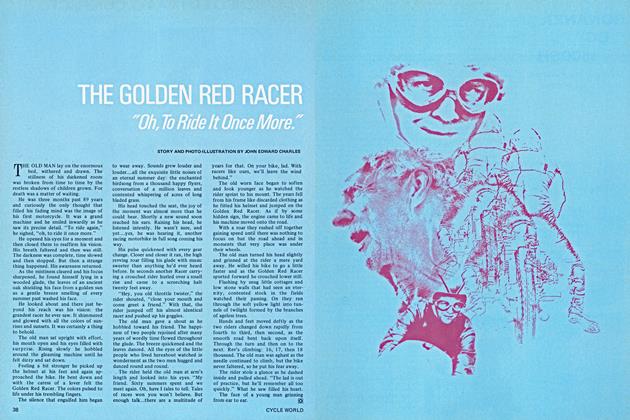

Features

FeaturesThe Golden Red Racer

OCTOBER 1969 By John Edward Charles