THE SERVICE DEPARTMENT

JOHN DUNN

BANTAM BOOSTING

I recently acquired an early (around 1950) 125-cc BSA Bantam two-cycle motorcycle and anticipate using it for trail riding. It is now in running condition, but the power leaves something to be desired. Most of my friends own modern 250s, and I would therefore appreciate any advice you can give with respect to tuning the engine.

Brian Calder Mineóla, N. Y.

During the early 1950s in England, the BSA Bantam was used extensively for several forms of racing. Development was carried out by private individuals, and speeds in excess of 90 mph were obtained from some of the more successful road racing machines. There is a section in Phil Irving’s book, “Tuning for Speed,” on two-stroke engines that thoroughly covers tuning the Bantam.

For your purpose, I would advise that the following engine modifications are carried out. The compression ratio is increased to 9.5:1, by removing material from the cylinder head face. It will be necessary to re-machine the squish bevel in the head to obtain adequate piston crown-to-head clearance. The clearance should be at least 0.045 in. with the gasket fitted.

To obtain a noticeable increase in horsepower, it will be necessary to improve the breathing ability of the engine. The standard unit is fitted with a carburetor of only 0.625 in. An appreciable gain in cross sectional area will be achieved by employing an instrument of 0.75-in. bore. An intake adaptor with the identical bore should be made, and either clamped or welded to the existing stub. The intake port can then be ported to match the larger internal diameter of the new intake adaptor. Remove no more than 0.031 in. from the top of the intake port in the cylinder. The port can be widened about 0.125 in. The bottom of the original port has a V in the center. This can be ported out until the port has a total height not to exceed 0.75 in. Try to obtain a curve to the bottom of the port instead of a straight edge. The whole of the intake tract should be blended to this new shape without creation of any drastic changes in cross-sectional area.

The top edge of the exhaust should not be made higher. The standard top edge is radiused. This can be straightened out to obtain some initial increase in area. The port can be widened slightly, preferably with radiused edges. The maximum width should not exceed 1.25 in. as piston ring breakage is likely to occur.

Some increase in the cross-sectional area of the transfer ports is necessary. It is best not to increase the height by more than 0.016 in., as greater benefit will be obtained from widening the ports slightly and angling them toward the rear of the cylinder. It is essential that the incoming gas from the transfer ports moves toward the rear of the cylinder, as this will assist in scavenging the residual exhaust gases.

(Continued on page 22)

The transfers also should be checked for good alignment at the port joint at the crankcase face. Any step at this point should be blended in. Also, check that the cutaways in the sides of the piston line up with their corresponding port areas in the cylinder, again blending in any mismatch.

If the big end needs replacing, try to obtain the later type. From 1953 onward, the Bantam was provided with a bearing 0.125 in. wider, which obviously had a higher load carrying capacity.

A two-stroke is very critical with respect to correct carburetion. A slightly lean mixture at full load can quickly result in seizure or a holed piston. It is therefore better to start out on the rich side. Run the engine at full throttle in high gear. If the carburetion is rich, the engine will four-stroke. Decrease the main jet size in the smallest increments possible until it will just run at full throttle without four-stroking, then reduce the jet size another 10 cc in size.

It is necessary for a two-stroke engine to have a very small cylinder-to-piston clearance, in order to obtain a good gas seal. It is virtually impossible to break in a two-stroke engine (particularly on older designs) by running it for a long time on part load. It is necessary after a short period of part load running to run the machine at maximum speed in high gear for a few seconds, then remove the cylinder and inspect the piston for tight spots. These tight spots should be eased off, preferably with a rough file (the file marks have the effect of holding oil); then the engine should be reassembled. This procedure should be repeated until the machine can be run at maximum speed for several minutes without any sign of tightening.

The increase in compression ratio and output will make it necessary for a colder spark plug to be employed.

WORRIED

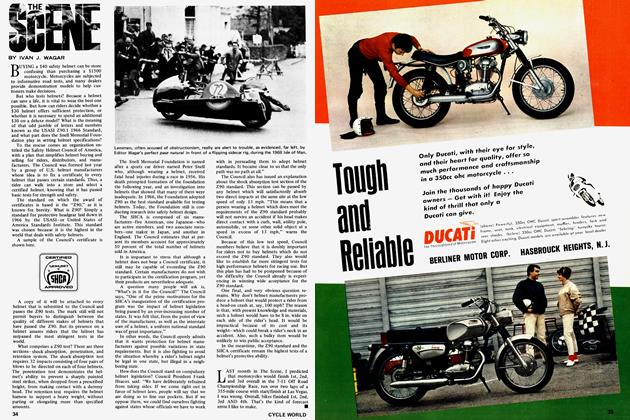

I am 16. Last summer I bought a 1967 Ducati 250 Monza after I worked for a year in a packinghouse. All my friends had little bikes, and they were tearing up after the first few thousand miles, so I bought a bigger one after the routine fight with my parents.

Here is what happened to my bike. I live in a hick town that is far from everything, so I had to ride it 30 miles from where I bought it to my house. I rode 60 mph one stretch, but just once. I shifted to second gear at 22 mph; I changed to third at 29 mph; I changed to fourth at 36 mph; and changed to fifth at 42, and have always shifted at those speeds, because the engine is revving pretty bad at those speeds. The engine starts to rumble after that, but if I want to drag I can get 30 in first, 50 in second, 60 in third, 65 in fourth, and 76 in top end. When the bike had 250 miles, I went into the woods for a day and ran it pretty hard. Then at about 400, I did it again because I liked it so much, even though I knew the bike wasn’t made for it. I have raced through the quarter about 10 times in the 4000 miles I have on it. I know I haven’t been very easy on it, but I know I haven’t been that bad to it. I didn ’t know very much about maintenance at the time and now I’m paying. I got the bike in the beginning of summer of ’67. With 3800 miles, in September, it went into cold storage. At Christmas I got to ride it for two weeks, and then it happened.

I did everything I should when I stored it, and changed the oil before I rode it. After about a day it had a knock. The dealer said it was slight, but it would have to be bored out when it started to burn oil. I knew my parents wouldn’t understand because they knew how much money I paid for the bike and thought it would last. It’s in storage again now, but in two weeks I will have it out. During the months between Christmas and summer I have done a great amount of reading on engines, and I want to learn how to fix engines myself. I am getting my motorcycle bored as soon as I get home. I have learned that it doesn’t have to smoke to need a bore job, and it still doesn’t smoke, but I put 400 miles on the cycle with piston slap. It still stops knocking when I don’t accelerate, but does knock when I accelerate, so I am sure it is piston slap and needs to be bored. Just to show you I didn’t know much about engines, I didn’t even know how to oil the brush on my points, so the arm wore down to the minimum gap setting, and I soon will need to replace my points, too. Now that you know the history of my bike, I would appreciate it if you could answer some of my questions.

First of all, I know how to replace the piston, but I don’t know whether anything else might be wrong with it because of its malfunction or break-in period of life. I don’t mean anything might be broken, but something may be worn and require replacement before something major goes wrong-like valves. I noticed that it was getting just slightly easier to kick start, but only took one kick and still has a lot of compression, especially since it is a Single. Other questions are, am I shifting too soon, and should I let it rumble instead of whine by turning the throttle faster? Or, should I do what I am doing now, which is turning the throttle slowly and thus it whines more at lower speeds until I reach a point where it rumbles? I shift just before it rumbles. That’s the best I can explain it. Also, I have used 30W oil during the summer all the time, but now I know it should have been 40W. In my town, 40W is still hard to get.

Also, I have always used lead-free gasoline. Was that good? Also, the dealer said the compression plate at the bottom of the cylinder would increase my top end by 6 mph. I can see that it would, but wouldn’t it increase the heat and cause some wear? If it didn’t cause wear, the manufacturer would have left it out and raised the compression ratio. I don’t want any more wear and want to make the bike last, but if the removable plate would increase the speed without noticeable wear, I could use the top end power. The top end is only 76, which is embarassing, but the low end is tremendous because I can take a lot of 250s and 305s through the quarter because I get top end in the quarter. Will it be worth it? I want just a strictly street bike to tour with that will last a long time.

I am not going to race it or take it in the woods anymore. I just hope it’s not too late to save the bike from wear. I have always kept it clean. I worked a long time for it and now realize my error. I will always have a bike and just can’t see, why everybody else doesn’t. They just don’t know what they are missing. Anyway, I wish I had another chance to take care of mine, but maybe your answers will prevent future trouble.

(Continued on page 24)

I am in such need of answers to these questions that I will pay for your trouble, but I will understand if you can’t answer. I guess that’s all (it’s enough) except that I think the mag does a great service in answering these letters. I bet everyone asking you for a favor says the same thing, but I am dead serious and will never bother you again, but will always buy the mag.

Mitchel Kaufman Bushnell, Fla.

Your problems are almost certainly due to lack of experience and knowledge, and also, a fair amount of abuse. It has always been my opinion that a newcomer to motorcycling should start with an inexpensive, older machine. This gives him the opportunity to learn without causing unnecessary damage to an expensive new machine. It also provides him with an early appreciation of the mechanical factors involved. No one becomes a proficient mechanic without a great deal of practical experience. During this period it is necessary to read as much as possible to understand “why.” It makes more sense to practice acts of maintenance and repair on an old machine than run the very likely risk of severely damaging a new machine through lack of experience. The same thing applies to the break-in period. Although there has been a lot written about the correct procedures to employ when breaking-in a machine, there is no

substitute for experience. Successful break-in is achieved by a good sense of feel that can only be learned through first-hand experience. If a rider starts on an old machine that requires regular attention to keep it going, he really will appreciate the new one when the time comes.

Your decision to restore the machine to its original condition and treat it with respect in the future is a good one. It is impossible for me to give you full instructions with respect to checking your engine thoroughly for wear within the medium of this letter. I would advise that if you are in any doubt whatsoever, get first-class advice before proceeding farther. When dismantling the engine or any component, lay the parts out in the order that they are dismantled on a clean and cleared area. Note particularly where washers and shims go. Also, take note which way a gasket is fitted. Sometimes a gasket can be replaced incorrectly, blocking off an important oil hole. Clean all mechanical parts and lubricate them before assembly. Always double check all that you do, particularly with respect to valve and ignition timing.

I would advise that you do not remove the compression plate at this time. Try and get the machine into first-class condition and accept the standard performance of the machine for the time being. There will be plenty of opportunity to carry out modifications when you have gained more experience.

WHAT TO DO?

I recently had a misfortune with my Honda 305 scrambler. The left piston and crankshaft

broke. I hardly rev it too high, but will those little “missing second” incidents cause that much damage, or could my engine have been considerably worn when I bought it five months ago?

I also have $120 more to pay, and the repair bill will break $200. Would you have it completely rebuilt with 75,000 on it, or pay off the bank and try again with a new one with warranty?

Dee Stearns Raleigh, N.C.

Your scrambler in its present condition (blown engine) is worth very little. The best you could hope for is enough to pay off the money you still owe the bank. Seventy thousand miles is a lot from any motorcycle currently manufactured, and if this is the first major problem, the machine does not owe you anything. However, if the machine has been well looked after in the past and other parts are in reasonable condition, it would not be uneconomical to have the engine/gearbox unit completely overhauled. If you give the dealer a free hand in overhauling the unit, insist on a reasonable warranty period to insure against labor or component part failures. If the repair shop is reliable, I am sure that the owner will stand behind the work. Have the repair shop dismantle the engine, then view the necessary replacement parts yourself before giving the okay to go ahead with the repairs. If you decide to go this route, do not skimp on anything. A new machine will cost from $700 to $1000. A first-class rebuild costs a possible maximum of $250.