CONTINENTAL REPORT

THE GENTLE ART OF BREAKING RECORDS

THE SALT FLATS at Bonneville are the dream of every world record aspirant, and a visit there is virtually essential if the contender is after the world's fastest crown to be gained over the flying mile, the mean of two runs in opposite directions. Attempts for that crown in the British Isles are impossible, for nowhere is the surface and distance available; but that does not deter our dragsters, or sprinters as we call them, from having a bash at world records.

Motor Cycle News sponsors a meeting each year to give the top men a chance to lower records and for this purpose uses a 2-mile long airstrip in Yorkshire. The name of Elvington is already known to regular readers of CW, but the 1967 efforts are entitled to rather greater coverage than usual, as it was an unusual meeting with quite shattering results. For the first time, the public were allowed to witness the two days of record attempts, and they saw 28 new world records in all set over the standing start quarter-mile, kilometer, and mile and flying kilometer. In some cases, it was a question of setting figures where none previously existed, but to beat one already on the books, it is necessary to improve on it by at least one percent.

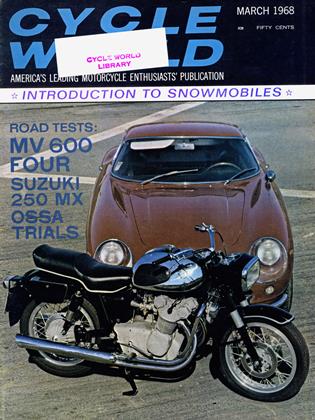

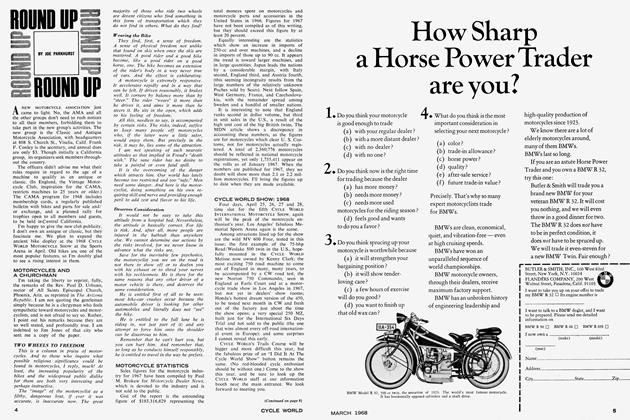

Several national records were also set, but these are of no interest to readers of an international magazine, like CW, except in one case — that of George Brown who refused to accept the FIM ruling that a man over the age of 55 should not be permitted to set records. George proved his point with a national record for the flying kilometer at 13.03 sec. against Hagon's world figure of 15.93 sec., and he beat his own standing-start mile figure of 31.44 sec. with a magnificent 27.98 sec., both set in the 1300-cc class.

A few days later at the FIM congress in Vienna the whole question of age and record breaking was reconsidered, and it was agreed that from 1968, those over 55 could attempt records up to 10 kilometers distance, subject to the individual passing two independent medical tests. It was then realized that the over-55 ban was not due to start until 1968, but Brown was denied ratification of his national records as new world figures because at the time he did not hold an international license. Bitterly disappointed at the news. Brown nevertheless intends to start work on two new machines, one for quarter-mile records and the other to fulfill his ambition to be the first man to do 200 mph in the UK.

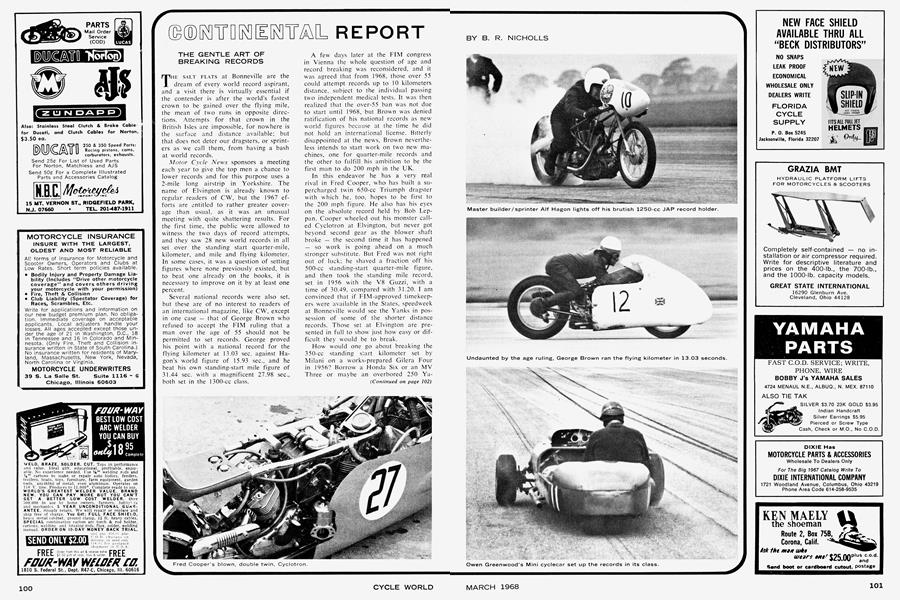

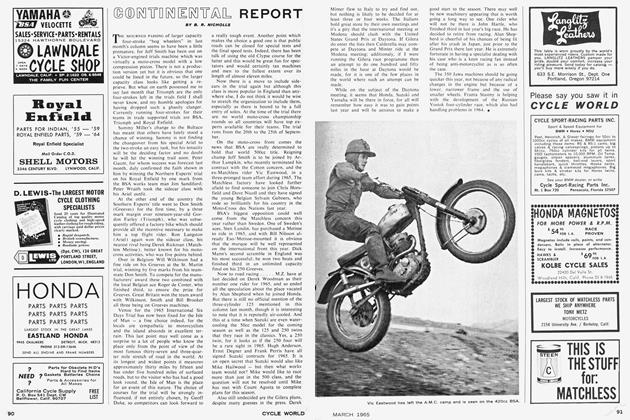

In this endeavor he has a very real rival in Fred Cooper, who has built a supercharged twin 650-cc Triumph dragster with which he, too, hopes to be first to the 200 mph figure. He also has his eyes on the absolute record held by Bob Leppan. Cooper wheeled out his monster called Cyclotron at Elvington, but never got beyond second gear as the blower shaft broke — the second time it has happened — so work is going ahead on a much stronger substitute. But Fred was not right out of luck; he shaved a fraction off his 500-cc standing-start quarter-mile figure, and then took the standing mile record, set in 1956 with the V8 Guzzi, with a time of 30.49, compared with 31.20. I am convinced that if FIM-approved timekeepers were available in the States, speedweek at Bonneville would see the Yanks in possession of some of the shorter distance records. Those set at Elvington are presented in full to show just how easy or difficult they would be to break.

How would one go about breaking the 350-cc standing start kilometer set by Milani on a works-prepared Gilera Four in 1956? Borrow a Honda Six or an MV Three or maybe an overbored 250 Yamaha Four. Bill Orris prepared a basically 1934 Rudge to trim that record from 23.22 sec. to 22.51, and then for good measure, in the standing start mile took the Lorenzetti works Guzzi figure down from 34.90 to 34.06. Both these records were set a decade ago, and were bound to be broken sooner or later. But, for these records to fall to a single cylinder pushrod engine, even if it has a four-valve head, speaks volumes for the mechanical ability of Orris, who aptly calls his machine The Menace.

(Continued on page 102)

B. R. NICHOLLS

Smallest capacity machine was a 79-cc Suzuki going for 100-cc class records. It was ridden by Jim Franklin, who knocked about 6 sec. off both the standing start mile and kilometer figures set in 1925 by a Frenchman on a machine called a Train, of all things.

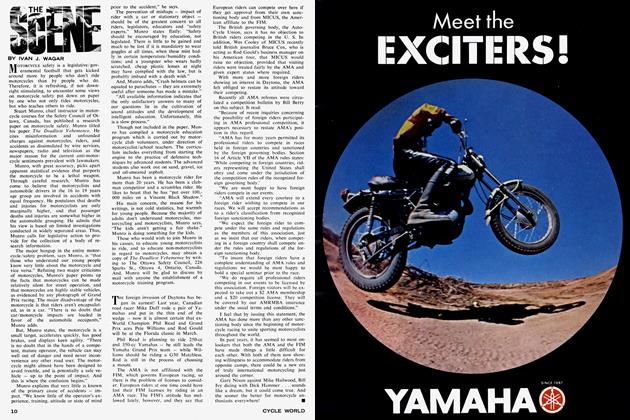

John McKiernan, in his first season of sprinting, with a blown 750-cc Triumph sidecar took two prewar records from BMW, set by Ernst Henne in the 1930s. Yes, it was all happening at once. Tony Brown took father George's 1300-cc standing start kilometer sidecar record down to 19.77 from 21.61 sec. In the new cyclecar section, that is a three wheeler laying three tracks, as opposed to a sidecar which only lays two. The dreaded Mini Special of Owen Greenwood with the 1300-cc class engine set four world records. Every meeting like this has its heartbreak story, and this year it belongs to Martin Roberts who, with his 750 supercharged Triumph, broke the standing start kilometer record, but failed to get it ratified as it was .007 percent below the 1 percent improvement required. ■