JODY NICHOLAS

He's Musical, Aerodynamic And Very Quick on Bikes

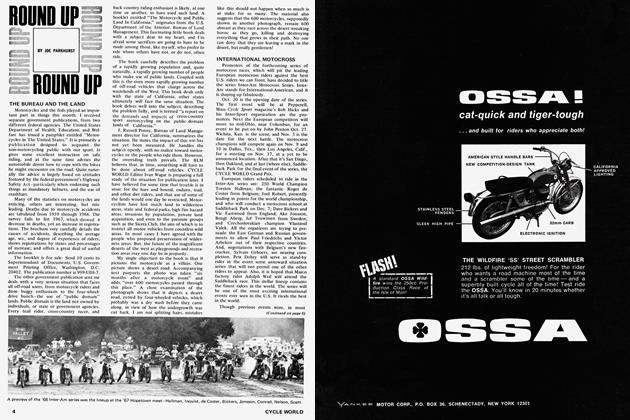

WHILE CAL Rayborn, Gary Nixon, and the gang complete the season-long struggle for AMA points, fellow racer Jody Nicholas is piloting U.S. Navy aircraft over Vietnamese waters.

He might have been with his racing buddies if he had accepted the two-year hitch in the Army that most young Americans undergo. Instead, when in 1966 he became eligible for the draft, Jody volunteered to serve more than five years in the Navy.

To motorcyclists, the decision may seem a sad waste of talent. Jody disagrees. His argument is this: “When I knew I had to enter the services, I thought I might as well do something worthwhile.” He considered that Army life might be too dull, and the pay too meagre. So, he replaced it with the challenge of learning to operate aircraft from the slender decks of carriers, and the opportunity to become an officer-he’s now a lieutenant junior grade. The additional three years of service, and the consequent interruption to his racing program, are burdens he willingly carries.

Racing motorcyclists are renowned for their addiction to the sport. Rarely, if ever, does a rider as skillful and successful as Jody choose an alternative career that so severely restricts racing. But, his decision does not seem so strange, when compared with the diverse and exciting incidents packed into his 24 years.

Following his parents’ wish, he became an accomplished violinist, playing in a number of youth orchestras and chamber music groups. He studied languages at the University of the South, in Sewanee, Tenn. In the summers, his talents as a kind of teen-aged prodigy of motorcycling enabled him to earn a considerable portion of the cost of his college education. As a nervous 16-year-old, he won the first road race he ever entered-not on the gravelly perimeter of some disused airfield, but at Daytona, the most revered circuit in America.

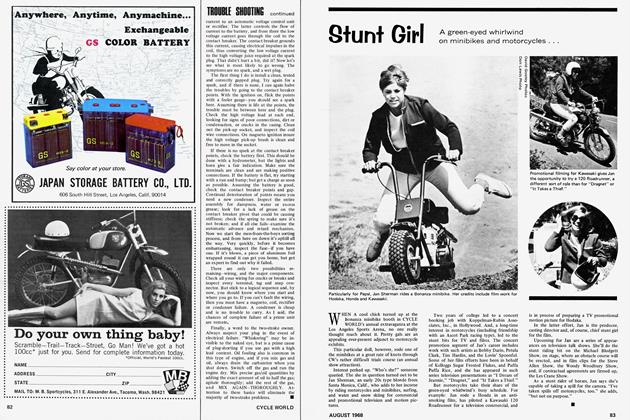

Activity in flight training school enforced Jody’s temporary retirement from racing from the 1966 Daytona event to February of this year. Then, based at San Diego, Calif., he sought out rider and tuner Don Vesco, who runs a motorcycle business nearby. On an ex-Daytona BSA, owned by the factory, but maintained by Vesco, Jody cleaned up his heat, semi, and the main at his first meeting on return to competition.

Riding the BSA, equipped with a 650-cc engine, a 500 BSA, and a 250 Yamaha, Jody swept to a series of wins and high placings at circuits throughout California. His first reacquaintance with all the AMA aces came at the Loudon 100-miler in July. Could he repeat the searing form of his pre-Navy days? Jody says, “After two years away from racing, I found I had to recondition all my reflexes. I knew what to do, but making my body obey my mind took quite a while. For some reason, I didn’t feel comfortable at Loudon. Two crashes during practice didn’t help.”

Despite the spills, Jody made 3rd place in the big race, placing his 350 Yamaha behind Cal Rayborn and Gary Nixon. In the 250 race, he crashed while in 2nd place.

Now, Navy duties again have interrupted racing. At this moment Jody is spending a seven-month term in the Tonkin Gulf, flying piston-engined Grumman early warning radar aircraft. He and his shipmates operate round the clock for 30-day periods, searching out enemy shipping. Jody talks of his flying in a matter-of-fact way: “It’s pretty safe because we don’t get too close to shore. In fact a six-hour flight tends to get boring after a couple of hours. The difficult parts are takeoffs and landings. From 2000 ft. the deck of an aircraft carrier looks like a postage stamp. Landing requires the most precise form of flying a pilot can do. We aim at the reflection of a beam of light, and as we pass over the end of the carrier deck we have to be accurate within 5 ft., in terms of vertical height. The aircraft is then doing just over 100 mph, and at that speed it’s not very responsive.”

The whole business sounds as though it requires similar qualities to those demanded of a top motorcyclist-swift reflexes, sharp eyesight, cool thinking, and an ability to make quick decisions during rapidly changing circumstances. If so, Jody has been in training for his pilot’s job ever since, at the age of 12, he rode his first motorcycle, a rigid framed, 500-cc Royal Enfield.

The years between the Enfield and his road race debut at Daytona were filled with “various and sundry” motorcycles, providing Jody with experience of street riding in the area round his home town of Nashville, Tenn., and, in 1957, an entry into motorcycle sport in the form of local scrambles. His efforts on a 250-cc BSA C15 scrambler encouraged the BSA Eastern people to offer Jody a bike for the Sportsman’s event at Daytona in 1960.

(Continued on page 95)

Continued from page 71

“Those C15s were really competitive then,” he says of the little Singles. “Power output was close to 30 hp, and top speed must have been about 115 mph.” Even after his somewhat sensational win at the Florida circuit, Jody didn’t realize that road racing was to become his speciality. “I had to travel about 800 miles from my home to find a road race,” he recalls. “That meant that I couldn’t study what other riders were doing, and 1 couldn’t talk to anyone who knew much about the sport. All I had was motorcycle magazines, and I probably lifted a few ideas from them.”

The following year, 1961, Jody pulled a fast one on the AMA by changing from Sportsman to Amateur status while still under 18, the “legal” age for such a move. He altered his birth date on a document, convinced his parents to sign it, and then forwarded the paper to the AMA authorities. “My folks didn’t really know what they were signing, because they had had to deal with so many other papers for me,” says Jody.

So, as 17-year-old high school kid, Jody mounted his factory BSA Gold Star and rushed off to win the Amateur race at Daytona. That was quite a feat for a youth who officially was too young to be in the race, but Jody followed up with wins in the Amateur section at the Watkins Glen and Loudon road races, and the Springfield 1-mile dirt track.

Logically, the next step was to move to Expert grading-which he did, in time for the 1962 season. His run of wins stopped, temporarily, as he clashed with the top names of the AMA circuit that year. Perhaps more important, he learned a lot, and achieved some good placings.

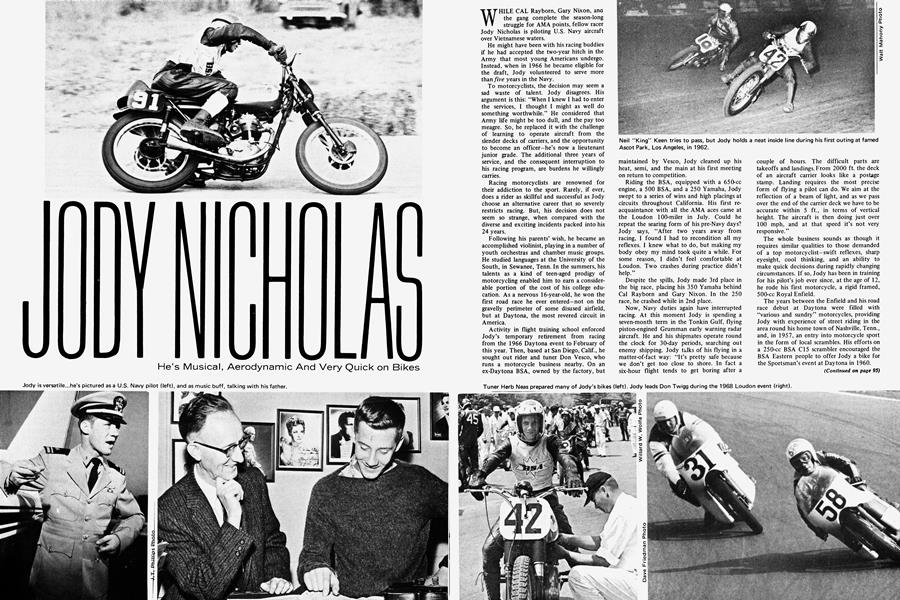

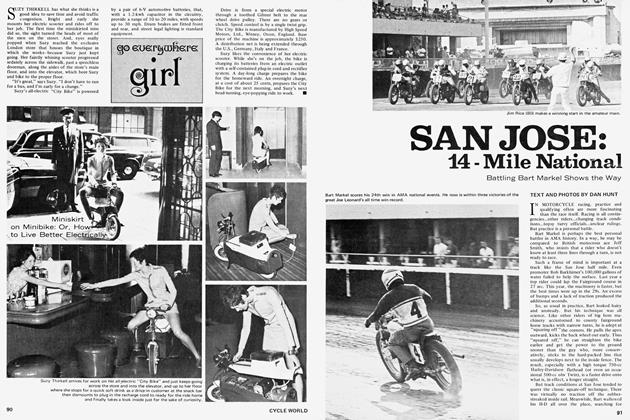

Proof of his ability as a dirt track rider was not really needed, but Jody provided it during a month-long racing excursion at the famed Ascot half-mile in Los Angeles, Calif. No one really took much notice of the slightly-built schoolkid. He might be quick on pavement, but Ascot has its specialists who race the track every Friday night of its 33-week season. These men know the track, and their bikes are set up solely for Ascot’s tricky, clay-surfaced turns.

When Jody arrived at Ascot it was in the wake of the respected “BSA Wrecking Crew.” This gang cleaned up most of the prize money. The “Crew,” comprised of Jack O’Brien, Stu Morley, Neil Keen and AÍ Gunter, weren’t about to allow any teen-ager from Tennessee to interrupt their reign.

As it turned out, Jody didn’t produce any fairy-tale wins at Ascot. The combination of a strange track and the ability of the Ascot specialists assured that. But, on his first night out, Jody surprised many riders by gunning into 5th place in the final. He thrust his Gold Star into the turns in an aggressive but economical style that was pleasant to watch...and, the following week, earned him a 6th in the final. Minor machine troubles then intervened to slow his progress a little. His final effort on the track was on the night the AMA National event was run. Jody missed making the final by a frustrating 2 ft., the distance that separated him from 4th place in his heat.

(Continued on page 96)

Continued from page 95

Jody’s reputation could have survived 1963 on just one race, the Loudon National road race. On his 50-bhp Gold Star, he powered off into the lead, chased by now retired George Roeder, on a Harley-Davidson. All went to plan until Jody slid off on the final lap, allowing Roeder to take the lead. But Jody leaped back onto the BSA, and chased and caught a startled Roeder! The crowd went wild, and Jody collected a total of $1750 in prize money.

“I had been keeping about 5 or 6 sec. in front of George,” he says. “But then I dropped it on this 20-mph hairpin just as I began the last lap. The engine didn’t stall, because I had the clutch in and the throttle open before I hit the ground. By the time I picked up the bike, I was about 50 yards behind George. There was less than a mile to go but I managed to outbrake him on one of the turns. I think he just didn’t expect me to recover so quickly.”

His winning time of 1 hr., 35 min., 47.7 sec., carved 30 sec. off the previous race record, held by Dick Mann.

It was really Jody’s year. He collected another $1300 for winning the Meadowdale, 111., 150-mile National. This time the misfortunes happened to someone else-Dick Hammer, who then was riding a HarleyDavidson. Dick used a massive fuel tank, holding some 8 gal., so that he could complete the distance without pitting. Jody, however, planned a stop to replenish his smaller tank. He built up a strong lead over Hammer, but after the pit stop, Dick was 26 sec. ahead, in 1st place. Jody hauled it back to 17 sec., but with two laps remaining it seemed that Hammer was a certain winner.

But it was not to be. Hammer collected a flat tire about two laps from the finish, leaving Jody an open road. In the 250 event, he started from the last row of the grid, after carburetion problems had marred his practice times. But by Lap 4 he had swept his Yamaha into the lead, and for the entire race kept Gary Nixon a safe 9-15 sec. behind.

In the spring of 1964 Jody again turned from school to the racetracks, this time with a contract to ride factory Bultacos. He remembers the little “ ’Tacos,” along with the Gold Stars, as the finest bikes he has ridden. They provided him with a string of wins, but also with a series of disappointments for what he calls “Mickey Mouse reasons.”

“For instance, in 1965 I won my class at the Canadian International Grand Prix. We drove all the following night to get to the Cleveland 100-miler, and I led that until 10 laps from the end, when the points closed up. All sorts of silly things like that happened,” says Jody.

Despite the mechanical setbacks, he still enjoyed many wins and placings, and, by this time, had become a kind of “racer’s racer.” He quit flat track events in 1963 because of the long distances involved and because, he explains, “The only times I got hurt were when I went through the fence on the half-mile tracks.” But he kept going faster and faster on the pavement circuits. Dick Mann, one of the greats of American motorcycle racing, once said, “When Jody pulled into the pits, we knew we could say ‘goodby’ to 1st place. His 250 Bultaco was giving away 5 bhp to the Yamahas, but he still was capable of beating everyone.”

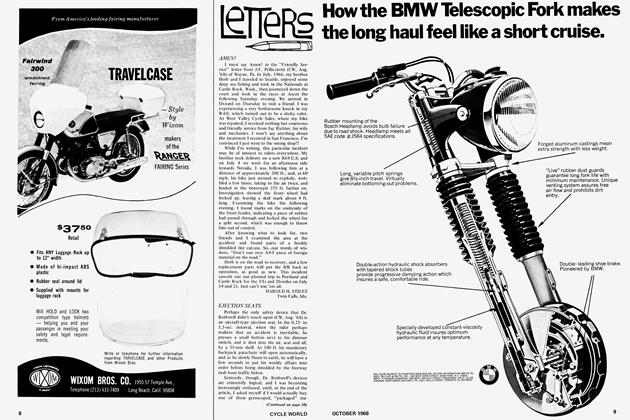

While Jody has earned praise from fellow riders, he acknowledges the help he received from men who provided him with machines. In particular, he has warm words of thanks for BSA specialist Herb Neas, and former Bultaco man John Taylor.

Neas is one of those magicians of mechanics whose efforts are little known outside the corridors and workshops of the motorcycle industry. As shop foreman and racing boss at BSA Eastern headquarters in Nutley, N.J., Herb for many years has been coaxing power from BSA engines. He was the man who tuned the Cl5 for Jody’s first road race outing in 1960, and six years later, at Jody’s final track outing before his Navy hitch, Herb still was behind the engine preparation,

Jody said, “He has done more to develop the Gold Star engine than anyone else in this country. Herb is the guy who made the Gold Stars reliable for 200-mile races.”

John Taylor now is the driving force behind the Yankee project. But when Jody made his move to Bultaco mounts, John, as sales manager for Cemoto East, was responsible for the offer of bikes.

Jody made no glorious and spectacular exit from the racing scene. Daytona of 1966 was his farewell ride before entering the Navy. And, in contrast to his earlier successes at the track, this was a disappointing year-ignition bothers early in the 200-miler forced him to retire his BSA Twin.

His move to the Navy interrupted a trip to Europe that he and Bob Hansen, of Hansen Matchless fame, had planned. Sr. Xavier Bulto, head of the Spanish Bultaco factory, was so impressed with Jody’s efforts on U.S. circuits that he promised to provide 125 and 250 machines for use on the trek to England and the Continent. Hansen planned to ship over his AJS 7R and Matchless G50 machines, and the boys had a big Dodge truck all ready for transportation.

But, Jody’s call to military service spoiled the trip. The cancellation is one of Jody’s bitterest disappointments in his racing career. Apart from that, he has no complaints with the Navy, particularly now that he is allowed to race in the intervals when he is based at San Diego.

The military call-up also meant a halt to Jody’s musical interests. His fragile violin had to remain at home in Nashville, where his father is assistant head of music in the music department at George Peabody College, and where his mother teaches piano. Also at home is his collection of 200 classical records. He professes a particular liking for “the romantic and impressionist Russians, Prokofiev and Rachmaninoff, and the impressionist French composers, Ravel and Debussy.”

Music and motorcycles will merge again when Jody completes his Navy duty in May 1971. It’s too early for him to predict what he will do when that time comes. Sure, he’ll continue racing. But, as ever, his interests will be so varied that motorcycles won’t consume all his time. To Jody, winning road races still will be, as it always has been, a fun hobby. ■