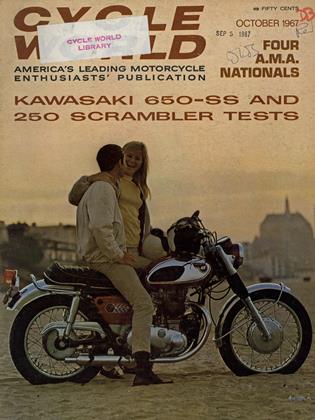

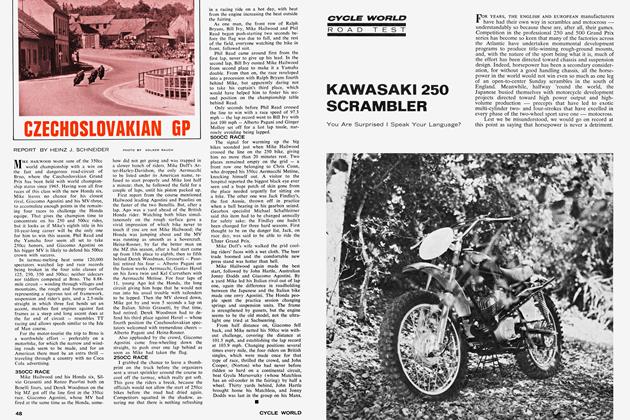

KAWASAKI W2 650SS

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

The SS Stands For Super Saki

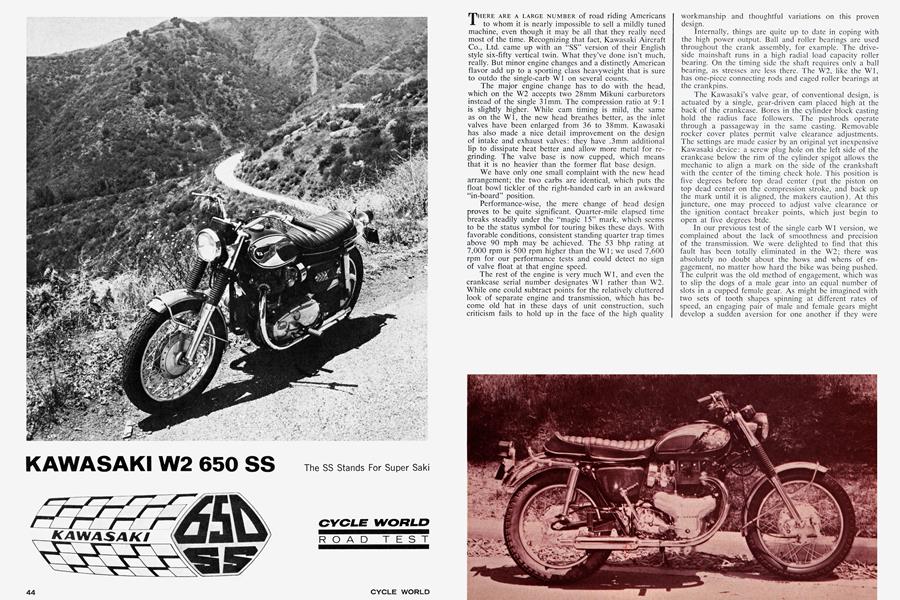

THERE ARE A LARGE NUMBER of road riding Americans to whom it is nearly impossible to sell a mildly tuned machine, even though it may be all that they really need most of the time. Recognizing that fact, Kawasaki Aircraft Co., Ltd. came up with an “SS” version of their English style six-fifty vertical twin. What they’ve done isn’t much, really. But minor engine changes and a distinctly American flavor add up to a sporting class heavyweight that is sure to outdo the single-carb W1 on several counts.

The major engine change has to do with the head, which on the W2 accepts two 28mm Mikuni carburetors instead of the single 31mm. The compression ratio at 9:1 is slightly higher. While cam timing is mild, the same as on the Wl, the new head breathes better, as the inlet valves have been enlarged from 36 to 38mm. Kawasaki has also made a nice detail improvement on the design of intake and exhaust valves: they have .3mm additional lip to dissipate heat better and allow more metal for regrinding. The valve base is now cupped, which means that it is no heavier than the former flat base design.

We have only one small complaint with the new head arrangement; the two carbs are identical, which puts the float bowl tickler of the right-handed carb in an awkward “in-board” position.

Performance-wise, the mere change of head design proves to be quite significant. Quarter-mile elapsed time breaks steadily under the “magic 15” mark, which seems to be the status symbol for touring bikes these days. With favorable conditions, consistent standing quarter trap times above 90 mph may be achieved. The 53 bhp rating at 7,000 rpm is 500 rpm higher than the Wl; we used 7,600 rpm for our performance tests and could detect no sign of valve float at that engine speed.

The rest of the engine is very much Wl, and even the crankcase serial number designates Wl rather than W2. While one could subtract points for the relatively cluttered look of separate engine and transmission, which has become old hat in these days of unit construction, such criticism fails to hold up in the face of the high quality workmanship and thoughtful variations on this proven design.

Internally, things are quite up to date in coping with the high power output. Ball and roller bearings are used throughout the crank assembly, for example. The driveside mainshaft runs in a high radial load capacity roller bearing. On the timing side the shaft requires only a ball bearing, as stresses are less there. The W2, like the Wl, has one-piece connecting rods and caged roller bearings at the crankpins.

The Kawasaki’s valve gear, of conventional design, is actuated by a single, gear-driven cam placed high at the back of the crankcase. Bores in the cylinder block casting hold the radius face followers. The pushrods operate through a passageway in the same casting. Removable rocker cover plates permit valve clearance adjustments. The settings are made easier by an original yet inexpensive Kawasaki device: a screw plug hole on the left side of the crankcase below the rim of the cylinder spigot allows the mechanic to align a mark on the side of the crankshaft with the center of the timing check hole. This position is five degrees before top dead center (put the piston on top dead center on the compression stroke, and back up the mark until it is aligned, the makers caution). At this juncture, one may proceed to adjust valve clearance or the ignition contact breaker points, which just begin to open at five degrees btdc.

In our previous test of the single carb Wl version, we complained about the lack of smoothness and precision of the transmission. We were delighted to find that this fault has been totally eliminated in the W2; there was absolutely no doubt about the hows and whens of engagement, no matter how hard the bike was being pushed. The culprit was the old method of engagement, which was to slip the dogs of a male gear into an equal number of slots in a cupped female gear. As might be imagined with two sets of tooth shapes spinning at different rates of speed, an engaging pair of male and female gears might develop a sudden aversion for one another if they were brought together in an indelicate manner. The redesigned transmission features the use of the engagement of knobs, or dogs, into holes on the corresponding female gear. As each receiving gear has six holes to the male ear’s three dogs, the “probability” of engagement is doubled and precision is increased. American Kawasaki tells us that the modification has also been extended to all new Wl single carb models, too.

Frame of the W2 is the same as that of the Wl, a “duplex” cradle, with oil-damped telescopic front forks and swinging arm rear end. The bike showed no tendency to oscillate or snake at freeway speeds, but due to the lack of rear damping, exhibited rear wheel hop on rough street surfaces. Balance of the bike, front to rear, seems good and while the machine admittedly weighs a lot, it shows no top heaviness at speed. Double damping of the steering head — using both a friction disc adjustable damper and a hydraulic strut between frame and lower fork bridge — results in a very calm, stable feeling front end.

As for touring comfort, our staff gave the W2 a high rating, although the agreement on all points was not unanimous. The bike has, for example, what sporting bloods would describe as an attractive exhaust note — that is to say, a midto high-range rap faintly reminiscent of the Chattanooga rattlers one may acquire at ye local parts house to increase the irritation power, if not power itself, of the machine. Unfortunately, those who don’t like to announce their arrival in such graphic terms will find it difficult to convert inexpensively to a more efficient silencer, as the head pipe and muffler on this model are integral.

Conversely, the mechanical noise from the engine itself seems almost nil, a nice plus factor in long-range riding where high, clattering overtones can really get a rider’s goat if present in extreme.

The handsome, pleated seat is the best example of Kawasaki’s efforts so far and cannot be faulted. The handlebars, with a little fiddling up or down, will prove comfortable to most riders. Parenthetically, we should note that the bars were the focal point for some engine vibration that proved irritating at steady road speeds. A soft metal or rubber insert around the bar at each clamping point would help.

The gas tank is on the broad side, but this does not affect comfort to any great extent, and has the advantage of a generous four-gallon capacity. The engine seems to be very economical as a result of its relatively mild cam timing. For the same reason the machine is quite docile in town at low speeds, and may be idled slowly away from the stoplight with hardly a transition between clutch in and clutch out. In high gear, the pulling power from 40 mph is surprising, considering the good top end performance.

The W2 is a clean machine, quite literally, and shows little evidence of oil loss. An offset primary chaincase contributes to the neatness of the machine on the left side; the cover joint is not in a direct line with the splash from the primary chain.

Finish and welding quality seems good. American Kawasaki informs us that the gauge of certain running gear metals (such as fenders and other stampings)has been increased to better resist vibration cracking — another example of the subtle, oft-invisible improvements to this big bore, which benefit the buying public and make for a superb all-around road machine. ■

KAWASAKI

650 W2 SS

$1,295

SPECIFICATIONS

:F:E:RFO RMANCE