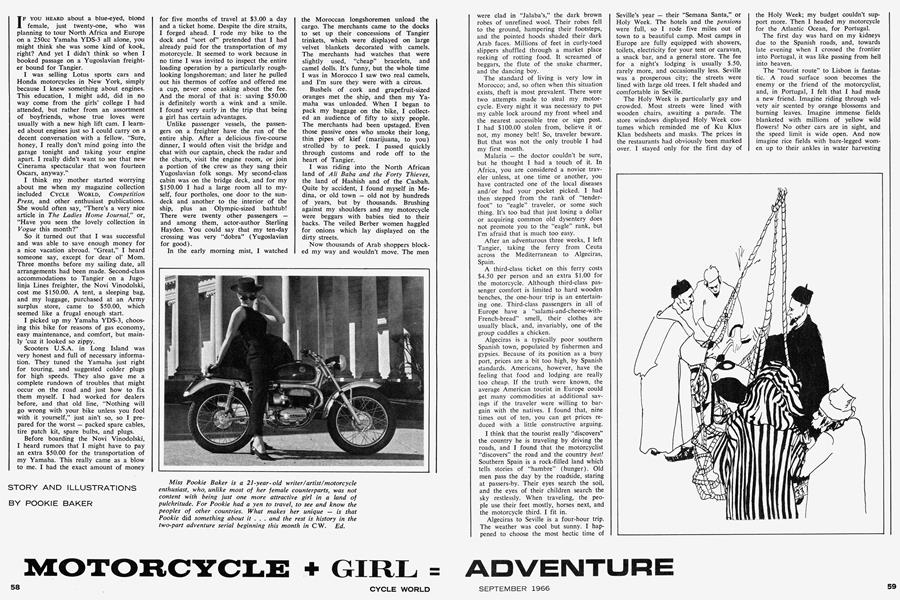

MOTORCYCLE + GIRL = ADVENTURE

POOKIE BAKER

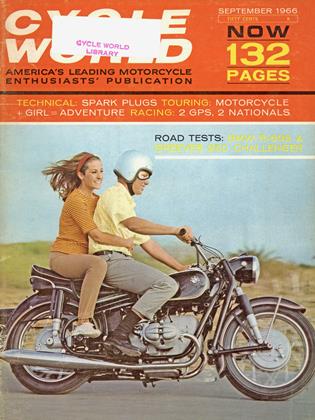

IF YOU HEARD about a blue-eyed, blond female, just twenty-one, who was planning to tour North Africa and Europe on a 250cc Yamaha YDS-3 all alone, you might think she was some kind of kook, right? And yet I didn't think so when I booked passage on a Yugoslavian freighter bound for Tangier.

I was selling Lotus sports cars and Honda motorcycles in New York, simply because I knew something about engines. This education, I might add, did in no way come from the girls' college I had attended, but rather from an assortment of boyfriends, whose true loves were usually with a new high lift cam. I learn ed about engines just so I could carry on a decent conversation with a fellow. "Sure, honey, I really don't mind going into the garage tonight and taking your engine apart. I really didn't want to see that new Cinerama spectacular that won fourteen Oscars, anyway."

I think my mother started worrying about me when my magazine collection included CYCLE WORLD, Competition Press, and other enthusiast publications. She would often say, "There's a very nice article in The Ladies Home Journal," or, "Have you seen the lovely collection in Vogue this month?"

So it turned out that I was successful and was able to save enough money for a nice vacation abroad. "Great," I heard someone say, except for dear ol' Mom. Three months before my sailing date, all arrangements had been made. Second-class accommodations to Tangier on a Jugolinja Lines freighter, the Novi Vinodolski, cost me $150.00. A tent, a sleeping bag, and my luggage, purchased at an Army surplus store, came to $50.00, which seemed like a frugal enough start.

I picked up my Yamaha YDS-3, choosing this bike for reasons of gas economy, easy maintenance, and comfort, but mainly 'cuz it looked so zippy.

Scooters U.S.A. in Long Island was very honest and full of necessary information. They tuned the Yamaha just right for touring, and suggested colder plugs for high speeds. They also gave me a complete rundown of troubles that might occur on the road and just how to fix them myself. I had worked for dealers before, and that old line, "Nothing will go wrong with your bike unless you fool with it yourself," just ain't so, so I prepared for the worst — packed spare cables, tire patch kit, spare bulbs, and plugs.

Before boarding the Novi Vinodolski, I heard rumors that I might have to pay an extra $50.00 for the transportation of my Yamaha. This really came as a blow to me. I had the exact amount of money for five months of travel at $3.00 a day and a ticket home. Despite the dire straits, I forged ahead. I rode my bike to the dock and "sort of" pretended that I had already paid for the transportation of my motorcycle. It seemed to work because in no time I was invited to inspect the entire loading operation by a particularly roughlooking longshoreman; and later he pulled out his thermos of coffee and offered me a cup, never once asking about the fee. And the moral of that is: saving $50.00 is definitely worth a wink and a smile. I found very early in the trip that being a girl has certain advantages.

Unlike passenger vessels, the passengers on a freighter have the run of the entire ship. After a delicious five-course dinner, I would often visit the bridge and chat with our captain, check the radar and the charts, visit the engine room, or join a portion of the crew as they sang their Yugoslavian folk songs. My second-class cabin was on the bridge deck, and for my $150.00 I had a large room all to myself, four portholes, one door to the sundeck and another to the interior of the ship, plus an Olympic-sized bathtub! There were twenty other passengers — and among them, actor-author Sterling Hayden. You could say that my ten-day crossing was very "dobra" (Yugoslavian for good).

In the early morning mist, I watched the Moroccan longshoremen unload the cargo. The merchants came to the docks to set up their concessions of Tangier trinkets, which were displayed on large velvet blankets decorated with camels. The merchants had watches that were slightly used, "cheap" bracelets, and camel dolls. It's funny, but the whole time I was in Morocco I saw two real camels, and I'm sure they were with a circus.

Bushels of cork and grapefruit-sized oranges met the ship, and then my Yamaha was unloaded. When I began to pack my baggage on the bike, I collected an audience of fifty to sixty people. The merchants had been upstaged. Even those passive ones who smoke their long, thin pipes of kief (marijuana, to you) strolled by to peek. I passed quickly through customs and rode off to the heart of Tangier.

I was riding into the North African land of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, the land of Hashish and of the Casbah. Quite by accident, I found myself in Medina, or old town — old not by hundreds of years, but by thousands. Brushing against my shoulders and my motorcycle were beggars with babies tied to their backs. The veiled Berber women haggled for onions which lay displayed on the dirty streets.

Now thousands of Arab shoppers blocked my way and wouldn't move. The men were clad in "Jalaba's," the dark brown robes of unrefined wool. Their robes fell to the ground, hampering their footsteps, and the pointed hoods shaded their dark Arab faces. Millions of feet in curly-toed slippers shuffled through a market place reeking of rotting food. It screamed of beggars, the flute of the snake charmer, and the dancing boy.

The standard of living is very low in Morocco; and, so often when this situation exists, theft is most prevalent. There were two attempts made to steal my motorcycle. Every night it was necessary to put my cable lock around my front wheel and the nearest accessible tree or sign post. I had $100.00 stolen from, believe it or not, my money belt! So, traveler beware. But that was not the only trouble I had my first month.

Malaria — the doctor couldn't be sure, but he thought I had a touch of it. In Africa, you are considered a novice traveler unless, at one time or another, you have contracted one of the local diseases and/or had your pocket picked. I had then stepped from the rank of "tenderfoot" to "eagle" traveler, or some such thing. It's too bad that just losing a dollar or acquiring common old dysentery does not promote you to the "eagle" rank, but I'm afraid that is much too easy.

After an adventurous three weeks, I left Tangier, taking the ferry from Ceuta across the Mediterranean to Algeciras, Spain.

A third-class ticket on this ferry costs $4.50 per person and an extra $1.00 for the motorcycle. Although third-class passenger comfort is limited to hard wooden benches, the one-hour trip is an entertaining one. Third-class passengers in all of Europe have a "salami-and-cheese-withFrench-bread" smell, their clothes are usually black, and, invariably, one of the group cuddles a chicken.

Algeciras is a typically poor southern Spanish town, populated by fishermen and gypsies. Because of its position as a busy port, prices are a bit too high, by Spanish standards. Americans, however, have the feeling that food and lodging are really too cheap. If the truth were known, the average American tourist in Europe could get many commodities at additional savings if the traveler were willing to bargain with the natives. I found that, nine times out of ten, you can get prices reduced with a little constructive arguing.

I think that the tourist really "discovers" the country he is traveling by driving the roads, and I found that the motorcyclist "discovers" the road and the country best! Southern Spain is a rock-filled land which tells stories of "hambre" (hunger). Old men pass the day by the roadside, staring at passers-by. Their eyes search the soil, and the eyes of their children search the sky restlessly. When traveling, the people use their feet mostly, horses next, and the motorcycle third. I fit in.

Algeciras to Seville is a four-hour trip. The weather was cool but sunny. I happened to choose the most hectic time of Seville's year — their "Semana Santa," or Holy Week. The hotels and the pensions were full, so I rode five miles out of town to a beautiful camp. Most camps in Europe are fully equipped with showers, toilets, electricity for your tent or caravan, a snack bar, and a general store. The fee for a night's lodging is usually $.50, rarely more, and occasionally less. Seville was a prosperous city; the streets were lined with large old trees. I felt shaded and comfortable in Seville.

The Holy Week is particularly gay and crowded. Most streets were lined with wooden chairs, awaiting a parade. The store windows displayed Holy Week costumes which reminded me of Ku Klux Klan bedsheets and masks. The prices in the restaurants had obviously been marked over. I stayed only for the first day of the Holy Week; my budget couldn't support more. Then I headed my motorcycle for the Atlantic Ocean, for Portugal.

The first day was hard on my kidneys due to the Spanish roads, and, towards late evening when I crossed the frontier into Portugal, it was like passing from hell into heaven.

The "tourist route" to Lisbon is fantastic. A road surface soon becomes the enemy or the friend of the motorcyclist, and, in Portugal, I felt that I had made a new friend. Imagine riding through velvety air scented by orange blossoms and burning leaves. Imagine immense fields blanketed with millions of yellow wild flowers! No other cars are in sight, and the speed limit is wide open. And now imagine rice fields with bare-legged women up to their ankles in water harvesting the crop. All of a sudden, you are in Lisbon.

Before entering Portugal I was told that in Lisbon the only place to stay is the "Parque Municipal" camp and that all signs and roads led to it. This spectacular campsite is some three miles from the heart of the city in Lisbon's Municipal Park, and is truly the number one camp in all of Europe. It boasts a modern supermarket, post office, bank, bar and restaurant, playground, washing machines and dryers, electricity for tents, and a billiard room. Hot showers twenty-four hours a day, an Olympic-sized swimming pool, two basketball courts, two tennis courts, and two volleyball courts add to your enjoyment. And, if this isn't enough for you, they have maid service available for your tent!

I become so spoiled that I spent two weeks in sunny Lisbon. The Portuguese people are very warm. A passing conversation can often lead to a warm friendship. I had an opportunity to meet a» wonderful couple. The gentleman I met while visiting the Federation International Motorcycliste's FMN in Lisbon invited me to dine with his family. We conversed in Spanish, a language he could understand easily, because Portuguese is similar to Spanish. That night, I learned a good deal about the Portuguese. Carlos and Lavinia da Silva's apartment was very nice, but, on the way to their home, I had to pass through the slum area which is hidden from most tourists. Portugal is a very poor country, but the average tourist would never know it. Lisbon makes most American cities look poverty-stricken. Lisbon has exquisite new steel and glass buildings, massive parks, and expensive shops; but beyond the high walls that line so many of the main streets in the small towns, and beyond the walls of trees and gardens in Lisbon, is poverty. When I asked Carlos about his government, he refused to answer pro or con, and simply said that he preferred not to discuss it.

Because of my interest in motorcycles, Carlos invited me to visit the Vespa club. This motor club business in Portugal is substantial. The Vespa club of Portugal has permanent offices in one of the more fashionable buildings in Lisbon. It has committee rooms, a bar and lounge with a full-time bartender and "full-time" music. Members take the club quite seriously, donating their time to the club's weekend activities, such as patrolling the highways around Lisbon for accidents on twenty-four-hour shifts. There are doctors and nurses on patrol who are radioed to the scene of accidents and render first aid to victims until the ambulance arrives.

The motorcycle sporting events in Portugal are quite limited, however. Roadracing is almost non-existent, as are flat track and scrambling. The national events are limited to the rally-type event, the twenty-four-hour runs, and an occasional trials meet. However, the Portuguese Federation assures me that in the future we will see more government-sponsored participation from Portugal.

It was a long, boring drive from Lisbon to Madrid, so I cut an easy three-day trip into a two-day "enduro."

Madrid was cold for April, with the temperature around 55°, and, because my riding gear had been chosen for warmer weather, I froze all the way. After searching for two hours, I discovered that all camps were closed until the first of May. Finally I staggered to the closest pension, only to find that the pension had no hot water. The next best solution to warm up the cold, weather-beaten body is to drink wine and then to sleep. This is what the Spaniards do for frostbite, and surprisingly enough, it tends to prevent colds.

The next day, I located a cheaper pension near Plaza Santa Anna for 50 pesetas a day, or about $.83. In Madrid, this is quite inexpensive. The norm is about 180 pesetas a day, or $3.00, so I felt quite lucky with my find.

In case you don't realize it, there is an entire cult of young travelers in Europe on all kinds of transportation. You get to recognize one of the members of the cult after some experience. He or she usually needs a haircut. They usually wear Levi's, and, frequently, the fellows are attempting to grow some sort of facial hair. This group can be found in the restaurants recommended in that great American classic, Europe on Five Dollars a Day. These people will be full of interesting information about the city you're in and/or the next you plan to visit. They know all the part-time work available and where to find inexpensive fun. The cult generally stays either at camps or in youth hostels, and their ages range from seventeen to forty years.

May 9th was to be the Grand Prix of Spain, held in Barcelona. It was only a few days away, so, despite rain and cold weather between the two cities, I departed for Barcelona.

On my journey, I had an emergency stop, when the bike suddenly lost all of its stability around corners. It seems that a "strategic" bolt holding my luggage rack in place had fallen off. I stopped next to a garage of sorts in a small village. No one was in sight. I peered into the garage and found a small, dirty boy sorting small, dirty bolts. I asked him where the manager was, but he didn't understand my Spanish. I directed him to my bike and pointed out that the bolt was missing, but he seemed too taken by all the chrome on my motorcycle to even notice what I was doing. I finally got his attention, and then he motioned me to follow him into the garage and to help him find a bolt that might fit. The bolts all had a look of antiquity, but I managed to pick one out that we both thought might fit. When we returned to the Yamaha, forty villagers had gathered around to inspect this shiny foreign motorcycle.

People all over the world have standard questions about a bike. First, they point to the speedometer and ask if it registers kilometers. You explain that it registers miles. Then, they all want to know how many "caballos," or horses, it has.

The high rpms intrigued my toothless audience, as did the U.S.A. license plate. The boy worked to fit the bolt. A farmer wandered into the garage and picked out another bolt that he wanted to try. One of the town's policemen argued that wire would fix it better. More people gathered, some standing off a bit while others wanted to see the problem firsthand. After at least ten people fitted ten different bolts of their particular choosing, we came upon one that would repair my rack. Everyone was pleased, as though their particular committee had solved a grave problem. And they waved me on with wishes of "bien viaje."

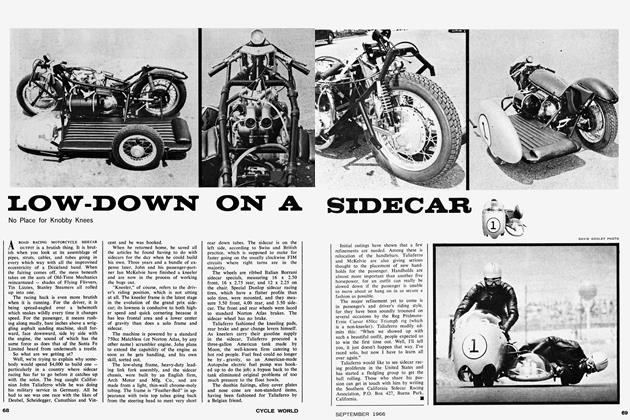

Riding into Barcelona was a delight. This busy, industrial city is always covered with a cloud of Spanish smog. Not far from the heart of the city I found a camp with a lovely swimming pool, snack bar, small store, and a pair of sleepy German shepherd watchdogs. I set up camp, and very shortly two young men with two road-racing bikes, a Cotton 250cc and a Bultaco 125, introduced themselves. It seems that Kevin Cass was the rider, and Graham Douglas, his mechanic. They were quite taken by my bike, and both had to test it. After sorting out their heavy Australian accents, we settled down to good motorcycle talk-

There were two other fellows with roadracing bikes in camp, and one, Ernst Degner, was riding for the Suzuki factory team. At night, after practice, the bike group sat around the pool and talked about the Montjuich course. It was all so exciting that I was convinced for one whole day that I wanted to be a road-racer.

A few days before the race, I went with a letter of introduction to the Bultaco motorcycle factory. I was to see Mr. John Grace, now Bultaco sales and export manager, and former road-racing champion. Johnny, as everyone calls him, was most accommodating when I told him of my travels and my interest in the motorcycle manufacturers of Spain. The factory was very busy at that time, preparing their bikes for the race and helping a dozen or so private entries with their Bultacos. Even so, Johnny showed me about the factory, and, as if a wish had come true, introduced me to the marvelous Sr. Francisco Xavier Bulto.

I wangled a press pass; so, on the day of the big race, wandered around the pits inspecting such exotic machines as the Benelli Four, the Honda Six, the East German MZs, etc., which were emitting their wondrous, ear-splitting exhaust sounds. The 250cc World Champion, Phil Read, of the Yamaha team, was great fun to talk with. I still don't know how he won the Grand Prix the next day. His total preparation in the pits seemed to consist of his shuffling around in a pair of rubber Japanese "zoris," joking with everybody in sight. If a completely relaxed attitude before a Grand Prix is a prerequisite for winning, Phil has the market cornered! The Yamaha mechanics were also offhanded about the entire affair. The Suzuki and Honda teams, on the other hand, put their large vans in a circle and hid from everyone. What a big secret! The bikes were covered with huge tarps, and the mechanics would go so far as to work on the secret "bomb" under the tarps so that no one, probably not even the team manager, knew what was going on. Surprise attack didn't pay off, however. Yamaha won the big race of the day, the 250cc event. In second place was the late Ramon Torras on a Bultaco, and third place went to Mike Duff on another Yamaha. I really felt like someone's lucky star that day.

An interesting experience during my stay in Barcelona was meeting an 86-yearold man whom I gave a ride on the back of my bike. The old gentleman (called "the Maestro") and I were introduced by a mutual friend at a dinner party. During the Maestro's lifetime, he had acquired several fortunes at one thing or another. His first, and perhaps most spectacular, was awarded him when he was sixteen.

The Maestro, as a boy, had been sold into slavery and, in fact, was the slave of an old Chinese mandarin. Though the entire court had left the mandarin because of his leprosy, the boy stayed. Upon the death of the old man, the boy inherited his entire treasure, part of which I had the pleasure of seeing. The Maestro's story is a unique one, touching the realm of fantasy. His twenty-room apartment resembles a junk antique store, but your eye is soon caught by a blue-white sparkle from a diamond-studded crown — and then you know the treasure is real. His maid sleeps in the bed of the great Queen Isabella, and is now called "Isabella." The Maestro speaks no English, so we roamed the twenty rooms with my new friend translating.

We had a marvelous dinner that night, the Maestro eating only rice. When we took the old man home, he spied my bike and began asking questions.

Did he want a ride? Si! And he got one! His one thought on the subject of motorcycles was that it was "like to fly as a bird, free and happy."

End of Part One