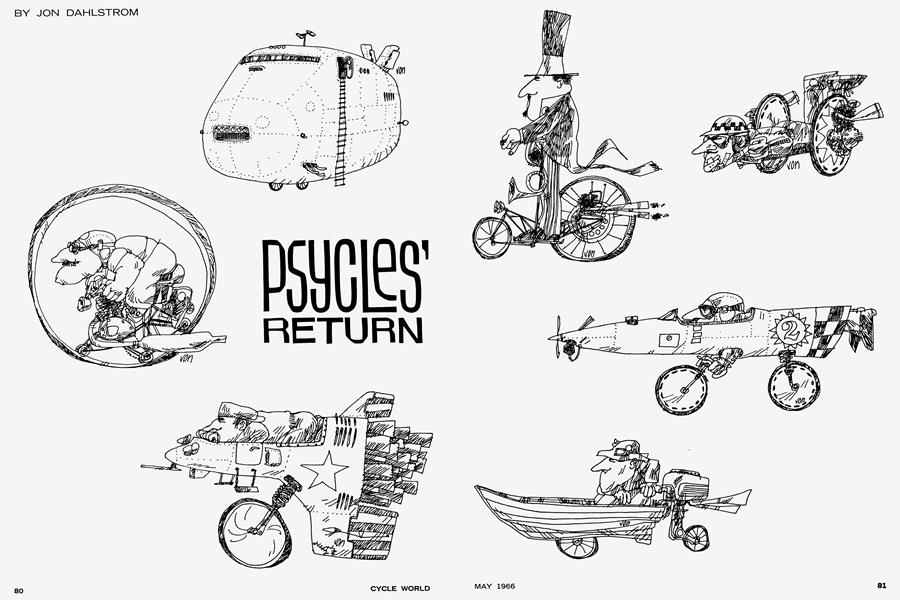

PSYCLES' RETURN

JON DAHLSTROM

CON

A CUSTOM MOTORCYCLE IS A WORK OF ART. . . SOMETIMES

WHERE I LIVE in Greenwich Village, every spring they have this outdoor art festival. It's a big deal with the tourists. Exhibits are lined up on the sidewalks and a judging committee awards cash prizes. Every artist in the village (that is to say, practically the whole population) works all winter perfecting something to show in the festival. Every artist, that is, except me.

I had planned to enter an exhibit this year as usual. I'm what they call a metal sculptor. I take pieces of iron from the junkyard and weld them into beautiful shapes and give them names like "Chaos" or "Sunburst" and people pay as much as $500 for them, which is pretty good considering scrap iron is only 5c a pound. But this year I got like sidetracked.

I'd just hoisted a fresh load of material up to my studio on the fifth floor of an old factory building in Greenwich Village and was sitting on the floor sorting out the pieces of rusty junk and waiting for inspiration when Von Grunch, the painter from California who lives next door, bursts into the studio looking to drink some of my wine.

"Hail Eardley, fellow striver in the Mills of Beauty!" this individual greets me as he helps himself to my jug of Chablis. I've known some really kook artists but Von Grunch makes Van Gogh look normal. He paints on old car doors with a spray gun and his major claim to immortality is that he hasn't sold a picture in his whole career. But he's as friendly as an old teddy bear and you can't help but like the guy.

"A little early for you to be paying social calls, isn't it?" I say. "What happened Von Grunch, did your compressor blow a gasket?"

"No, smartness. I just ran out of 'paint remover' " he winked, tipping the bottle into his beard.

"Help yourself."

"Really? Thanks." And he did, again, glancing from the pile of junk on the floor to me. "Sa-a-ay . . he said, licking his whiskers. "Isn't that an old Indian?"

"Where?" Knowing Von Grunch's weird sense of humor, I instinctively glanced behind me, half-expecting to find an elderly brave with upraised tomahawk. "What Indian?"

"Don't tell me that isn't an Indian motorcycle you've got there," said Von Grunch, scrabbling among the scrap iron and holding up various pieces for examination. "I never forget a crankcase. There's the frame . . . cylinder barrels . . . I'd say it was an old 1927 Scout. A noble savage if ever there was one." He looked at me with a trace of respect in his bloodshot eyes. "I didn't know you dug motorcycles."

"I don't. I dig scrap iron. This is just a pile of junk I bought from Horowitz the junkman for 54 a pound. I'm going to create a sculpture with it for the Spring Festival."

"Oh man," sighed Von Grunch pityingly. "Anybody can weld a bunch of angle iron into a shape that'll impress the tourists. But a '27 Indian Scout man, that's a work of art in its own right. If you cut up this beautiful frame to make a scarecrow for some Scarsdale patio why, that'd be like melting down the Statue of Liberty to cast piggy banks!"

"But I don't want a motorcycle," I argued, seeing the mad glint in my neighbor's eye. "I'm an artist not a ... a mechanic. Besides," I said, admitting the chief objection, "What would Sonya say?"

"Aha! The truth will out. You're afraid your beloved Sonya doesn't like motorcycles."

"You know good and well she doesn't. Ever since that taxi clipped her scooter she thinks anything on two wheels is a menace to life and limb."

"Females." Snorted the painter. "Leave us not consider their tender misgivings. Wait right here," he said, as if I was going any place, and bolted to his studio down the hall.

I continued to examine the pieces of junk, but all they suggested, now that Von Grunch mentioned it, was a motorcycle. Or perhaps a steel antelope? Von Grunch stomped back into the room carrying a battered picture album.

"I'll show you some real metal sculpture," he said opening the pages. The album was full of color photographs of motorcycles and cars, all painted in Von Grunch's crazy style. "This is what I used to do before I decided to kick the eating habit and go' aesthetic." He flipped to a picture of a glittering contraption that looked like a hallucination about to take flight — all upswoops and lightness. I blinked at the unexpected beauty of the thing. "What is it?" I gasped.

"That's your 1927 Indian Scout," explained Von Grunch with exaggerated patience. "With a bit of customizing and paint by yours truly."

Now he began to wave his hands like a conjurer and his voice fell to a hypnotic pitch. "Envision yourself Eardley my friend, astride this Pegasus of steel, master of the highways and byways, with your beloved Sonya clinging rapturously to your loins as you penetrate the farthest green reaches of New England hills. Far, far from the maddening crowd, holding a herd of harnessed horses in your grubby hand ... 'a loaf of bread, a jug of wine and thou, Sonya behind thee, singing in the wilderness . . "

" . . ah, 'twere wilderness enow.' " I finished, entranced by kinetic visions of my protruberant Sonya pressing against my . . .

"That's the idea. You'll thank me, Eardley. And I shall help you, yes I shall. It's the least I can do for all the happiness you've given me. Which reminds me . . ." he said, hefting the empty jug, "We are out of wine."

(Continued on page 122)

Well, we went at it literally hammer and tongs all winter, rebuilding the Indian. I bought tires and welded up freeform exhaust pipes and a pair of handlebars that looked like probing antennae. I would have been very happy except that whenever Sonya came to visit she would cast a critical eye over the work in progress and say something like "It's a wonderful concept, painting and plating all the elements in your design, Eardley darling. So different from the usual rusty texture of metal sculpture. I'm just certain it will win a prize in the Spring Festival." Or something like that, and she'd stand there smiling proudly at me and bulging so delightfully in all the right places that I didn't have the urge to cop out to what we were really making. My urges toward Sonya were of a much different nature.

"Don't worry," Von Grunch would say when she had gone, passing me the jug. "Just wait till she feasts her peepers on the only radically customized '27 Indian Scout in Greenwich Village. She'll throw her loving arms about you and give with a big, wet, kiss!" Maybe so; after all, the bike was going to be a masterpiece.

Von Grunch supervised the rebuilding of the engine in a little motorcycle shop on Long Island. When we hoisted the completed mill up to the studio via the block and tackle that I had for lowering heavy statues to the street, he explained what the mechanic had done: "She's full race, baby. 1 wish we had a dyno to run it on, but I'd guess she'll put out fifty horses!"

"For $200 I hope so," I said, bemoaning my shriveled bank balance. There was barely enough bread left for license and insurance.

"Well, we had to cut down Harley pistons and modify Cadillac intake and Packard exhaust valves to fit."

"Couldn't you have just left it stock?" I asked.

"Please!" Von Grunch was aghast. "Don't use profanity in my presence. Do you want to be one of those 'all show and no go' types?"

"Well . . ."

"Do you think for a minute I'd let one of my friends out in that blood-thirsty New York traffic without enough power to protect himself?"

"Well, gee . .

"Besides, there haven't been any parts available for this relic since World War Two. Well, gotta scoot. I know a sandal maker on McDougali Street who's just the guy to do a pleat and roll job on the seat." And away he went.

At last, just as the winter snow was melting in the gutters, we stood back and admired the gleaming red steed which perched delicately on its skinny wheels as if it were a rare bird about to fly away. "It sure is a sweetheart," I had to admit. Just then there was a knock at the door. "Speak of the devil," muttered Von Grunch as Sonya came in, talking a mile a minute.

"Eardley darling I just couldn't wait, I've simply got to see this mystery sculpture of yours. It must be finished by now because tomorrow morning is the Spring . . . EEEK! What's that?"

"Don't be frightened sweetheart," I soothed. "It's only a motorcycle."

"Only, he says," muttered Von Grunch. Then, "I'm going out for some more refreshments," and left. The coward.

"You . . . you mean this is what you two were so busy making all winter?"

"Yup. Isn't it a masterpiece?"

She cocked an eyebrow at the soaring handlebars, the thrusting pipes, the pendulous black mass of engine nestled under the rococo tank, and then at me as if she were deciding how I'd look in a straitjacket. "For some greasy-fingered mechanic, maybe. But you're supposed to be an Artist, Eardley. How you've disappointed me! I told everyone you were going to win first prize and all the time you were making a ... a plaything!" Her big brown eyes got all watery and I was undecided whether to be offended or apologize. Compassion finally won out.

"There, there, honey. I'm still an artist, but I had no inspiration for anything all winter but this. Call it a catharsis if you want, but wait till we ride together up in the green hills of New England this summer, away from the crowded city . .

She stamped her sandalled foot. "Eardley Blish, if you think for one minute I'll have anything to do with a motorcycle you're kookier than your friend Von Grunch! Those things are a . .

"A menace to life and limb," I interrupted wearily. "I know."

"And don't bother to call me," she fairly screamed, stomping out the door, "because to you I won't be in!" Slam!

What a scene. Gain a motorcycle and lose your girl. Sighing, I slumped on the Indian's seat and rested my chin in my hands. The door opened cautiously but it was only Von Grunch, shifty eyes surveying the room.

"Everything okay? No injuries?"

"Only a broken heart," I said, motioning him in.

"Got just the remedy for that disease," he chuckled, producing a jug. "Drown your sorrows, for tomorrow — tomorrow is another day," he sang, capering about fetching glasses and a corkscrew. Glumly I took the proffered glass, which Von Grunch kept filling. When one jug was empty he came up with another and finally my spirits, if not completely mended, were on the rise.

But when the sun began to lighten the sky over Brooklyn my malaise came back intensified. I didn't want any of the other girls Von Grunch guaranteed the bike would attract; I wanted Sonya. Pneumatic Sonya. And all up and down the street came the happy voices of other artists placing their canvases on the sidewalk for the judging, which would soon begin. It was the first year since I left art school that I had nothing to show in the festival.

"Forget it," counselled Von Grunch. "You'll go back to the torch and scrap iron a new man after your mechanical sabbatical this winter. Leave the prize money to the underprivileged types who have to hang around the city all summer and fight for standing room on the subways. You've got a new mistress, lad, who's just chafing her pistons to show you what she can do. I strongly urge nay, I insist we lower the lady to ground level right now so you can enjoy her favors this very day!"

"S'too early," I mumbled in my inebriated haze. "The hardware store isn't open."

"What's that got to do with anything?" Von Grunch wanted to know.

"Need a new rope for the hoist. Old one's 'bout frayed through."

"Nonsense," he argued, inspecting the rope. "I've seen you lift half a ton of junk with this. The Indian doesn't weigh more than three, four hundred pounds."

"Wanna sleep first." I protested.

"Work first, sleep later. Come on, before the sidewalk gets too crowded."

Groggily I stumbled to the high front windows and rigged the hoist on the beam. The rope looked all right, I guess, what I cotild see of it. Everything was kinda hazy.

We slung the rope around the forks and pushed the motorcycle over the sill until it dangled in midair, tail downward, reflecting sunlight from its polished surfaces. I looked down, dizzily, and saw a small crowd gathering to watch the descent. Anything draws a crowd in New York City. "I'd better go down and clear the way," I said. "Wait till you hear me holler, then let her come slowly." Von Grunch gave a tipsy salute and the machine lurched a little on the end of its rope.

"Oops," he grinned. "Better use both hands."

On the sidewalk a few friends hailed me. "Is that your secret project up there, Eard?" "Looks something like a motorcycle. What do you call it?" But I just smiled. They'd find out soon enough that I wasn't entering anything in the festival competition this year. I cleared a space on the sidewalk under the dangling machine and shouted to Von Grunch to lower away. The motorcycle slowly descended in short jerks, swiveling in the sunlight. It would drop a foot, stop, then drop another foot. I guessed Von Grunch had his hands full with the hoist. Then it dropped two feet and stopped. It was still four stories high. Then it dropped three feet and stopped with a jerk. Then it just dropped.

Slowly at first, then very fast the shining missile plunged to the thick cement sidewalk, trailing its broken rope like a fuse. When the echoes of its demise stopped resounding, Von Grunch's rumpled head emerged from the window five stories up. "What happened?" he said stupidly.

What happened was my beautiful new custom motorcycle was a total wreck. Only the handlebars, gearshift, and one lone exhaust pipe protruded from the heap of brightly polished rubble. A bloodshot eyeball on the mangled tank glared balefully upwards. I should have been despondent but for some reason my sense of humor asserted itself and all I could think was "Another redskin bit the dust."

Just then I felt a hand on my arm and turned to find Sonya, gasping as if she'd run all the way from her apartment in the Bronx. "Eardley, I'm sorry darling for the way I acted last night. I feel like such a shrew. Please say you forgive me. I'll even try to like your motorcycle."

I took her in my arms and suddenly the wreckage at my feet didn't matter any more. "No need to concern ourselves about that now," I said.

"Is that object yours?" a voice behind me asked. It was someone I'd never seen before, dressed in an ivy league suit and clean-shaven like a tourist from Madison Avenue. I nodded yes.

"What do you call it?" This pest continued.

"I call it a catastrophe!" I snarled. "Wanta make something of it?"

"Ooh," he fluttered, turning to a group he was with. "An Angry Young Man." They were writing something on clipboards and comparing notes.

"What are you guys?" I asked testily, "Reporters?"

"Goodness no," the man said primly. "We are the judging committee for the Spring Art Festival. And what is your name sir?"

I told them.

"Well," the Mad Ave type said with a glance at his cronies, "I don't think we need look any farther, do you, Committee?" The others shook their heads solemnly. "Then I hereby award First Prize in the Sculpture Division to the remarkably original creation, "Catastrophe" by Eardley Blish." And so saying he hung a blue ribbon on the ex-Indian's exhaust pipe.

"As you know Mr. Blish, there is a cash prize of two thousand dollars that goes with the award. You will receive your check as soon as your sculpture is delivered to the Museum of Modern Art. Congratulations on your amazing talent sir, and good day."

Suddenly I was surrounded with friends slapping my back and shaking hands and flashbulbs were popping in my eyès and Sonya was kissing me over and over and then all the excitement and lack of sleep caught up with me at once and I blinked out like a light.

". . .The technique is quite simple, really," I heard a familiar voice saying.

". . . Once the original design has been rendered in metal and paint, the artist positions the sculpture over an unyielding surface, ah . . . like a sidewalk, some fifty yards below, for the Moment of Truth, that final stroke of chance which completes the creation and baptizes it as a Work of Art. And gravity does the rest."

I opened my eyes to find that I was back upstairs on the couch and Von Grunch was talking to a group of reporters while Sonya placed cool cloths on my forehead. When he saw my eyes were open Von Grunch broke off his narrative. "Ah, he's conscious. Gentlemen, he's all yours."

"Your friend here has explained your techniques, Mr. Blish, and I must say they are unusual. We have only one question left. What do you plan to do with the prize money?"

I gave Von Grunch a wink and smiled at Sonya, who was wearing a low-cut peasant blouse that hid very little of her charm. "Buy a motorcycle," I told the reporter. "What else?"