GREEVES 250 TRAIL

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

GOOD GREEVES, CHARLIE BROWN!

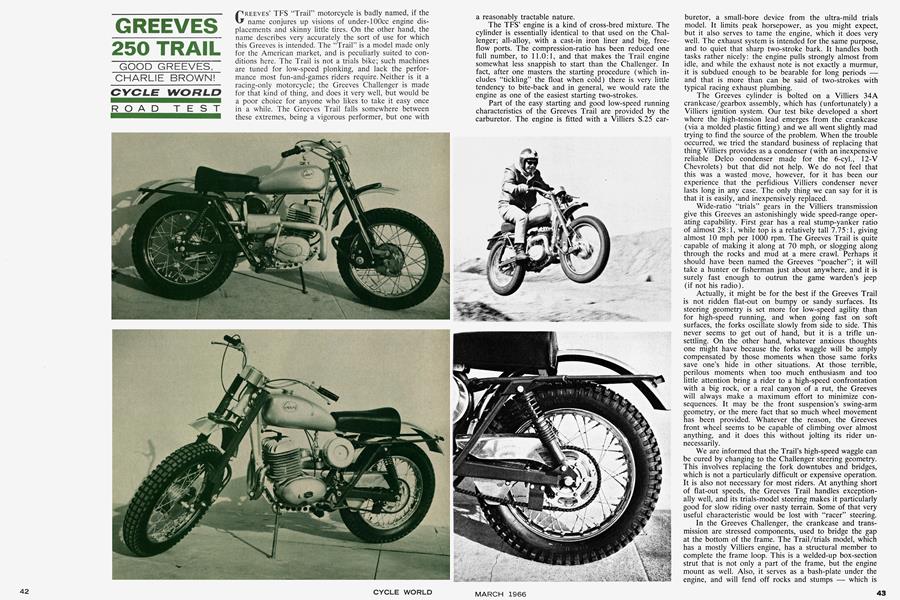

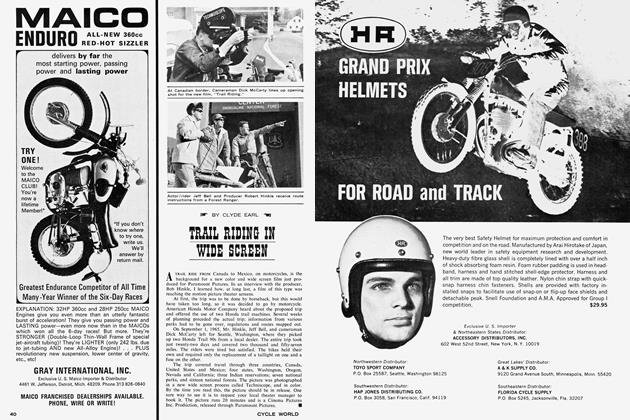

GREEVIES' TFS "Trail" motorcycle is badly named, if the name conjures up visions of under-lOOcc engine displacements and skinny little tires. On the other hand, the name describes very accurately the sort of use for which this Greeves is intended. The "Trail" is a model made only for the American market, and is peculiarly suited to conditions here. The Trail is not a trials bike; such machines are tuned for low-speed plonking, and lack the performance most fun-and-games riders require. Neither is it a racing-only motorcycle; the Greeves Challenger is made for that kind of thing, and does it very well, but would be a poor choice for anyone who likes to take it easy once in a while. The Greeves Trail falls somewhere between these extremes, being a vigorous performer, but one with a reasonably tractable nature.

The TFS' engine is a kind of cross-bred mixture. The cylinder is essentially identical to that used on the Chal lenger; all-alloy, with a cast-in iron liner and big, freeflow ports. The compression-ratio has been reduced one full number, to 11.0:1, and that makes the Trail engine somewhat less snappish to start than the Challenger. In fact, after one masters the starting procedure (which in cludes "tickling" the float when cold) there is very little tendency to bite-back and in general, we would rate the engine as one of the easiest startin2 two-strokes.

Part of the easy starting and g~od low-speed running characteristics of the Greeves Trail are provided by the carburetor. The engine is fitted with a Villiers S.25 carburetor, a small-bore device from the ultra-mild trials model. It limits peak horsepower, as you might expect, but it also serves to tame the engine, which it does very well. The exhaust system is intended for the same purpose, and to quiet that sharp two-stroke bark. It handles both tasks rather nicely: the engine pulls strongly almost from idle, and while the exhaust note is not exactly a murmur, it is subdued enough to be bearable for long periods -and that is more than can be said of two-strokes with typical racing exhaust plumbing.

The Gr~ves cylinder bolted on a Villiers 34A crankcase/gearbox assembly, which has (unfortunately) a Villiers ignition system. Our test bike developed a short where the high-tension lead emerges from the crankcase (via a molded plastic fitting) and we all went slightly mad trying to find the source of the problem. When the trouble occurred, we tried the standard business of replacing that thing Villiers provides as a condenser (with an inexpensive reliable Delco condenser made for the 6-cyl., 12-V Chevrolets) but that did not help. We do not feel that this was a wasted move, however, for it has been our experience that the perfidious Villiers condenser never lasts long in any case. The only thing we can say for it is that it is easily, and inexpensively replaced.

Wide-rati~ "trials" gears in the Villiers transmission give this Greeves an astonishingly wide speed-range oper ating capability. First gear has a real stump-yanker ratio of almost 28: 1, while top is a relatively tall 7.75: 1, giving almost 10 mph per 1000 rpm. The Greeves Trail is quite capable of making it along at 70 mph, or slogging along through the rocks and mud at a mere crawl. Perhaps it should have been named the Greeves "poacher"; it will take a hunter or fisherman just about anywhere, and it is surely fast enough to outrun the game warden's jeep (if not his radio).

Actually, it might be for the best if the Greeves Trail is not ridden flat-out on bumpy or sandy surfaces. Its steering geometry is set more for low-speed agility than for high-speed running, and when going fast on soft surfaces, the forks oscillate slowly from side to side. This never seems to get out of hand, but it is a trifle un settling. On the other hand, whatever anxious thoughts one might have because the forks waggle will be amply compensated by those moments when those same forks save one's hide in other situations. At those terrible, perilous moments when too much enthusiasm and too little attention bring a rider to a high-speed confrontation with a big rock, or a real canyon of a rut, the Greeves will always make a maximum effort to minimize con sequences. It may be the front suspension's swing-arm geometry, or the mere fact that so much wheel movement has been provided. Whatever the reason, the Greeves front wheel seems to be capable of climbing over almost anything, and it does this without jolting its rider un necessarily.

We are informed that the Trail's high-speed waggle can be cured by changing to the Challenger steering geometry. This involves replacing the fork downtubes and bridges, which is not a particularly difficult or expensive operation. It is also not necessary for most riders. At anything short of flat-out speeds, the Greeves Trail handles exception ally well, and its trials-model steering makes it particularly good for slow riding over nasty terrain. Some of that very useful characteristic would be lost with "racer" steering. In the Greeves Challenger, the crankcase and trans mission are stressed components, used to bridge the gap at the bottom of the frame. The Trail/trials model, which has a mostly Villiers engine, has a structural member to complete the frame ioop. This is a welded-up box-section strut that is not only a part of the frame, but the engine mount as well. Also, it serves as a bash-plate under the engine, and will fend off rocks and stumps - which is exceedingly useful in the sort of work for which the Trail is intended. And, there is also a measure of engine protection provided by the cast aluminum-alloy “frontbone” frame member.

As befits a machine made by long-time suppliers of dirt-pounding equipment, the Greeves has excellent handlebars, a comfortable seat and well-placed folding pegs. And, with a single exception, all of the controls are right: ballend levers, “quick” throttle twistgrip and all like that. Our single complaint is in regard to the gear-shift lever, which is too short to work very well. We don’t know what, if anything, can be done about this. To keep the end of the lever within toe-reach from the footpeg, it has been necessary to make the lever short — which means that the lever travel is short, and an abnormal amount of pressure is required to make gear changes. Lengthening the lever would improve the shift action, but would also move the business end of the lever so far forward that it would be necessary to lift one’s foot from the peg and reach to make a shift. With the gear change shaft positioned where it is on the transmission case, there isn’t much the buyer can do except become accustomed to the situation. Some sort of remote-link mechanism would correct things, but that sort of hardware always seems to get scraped away on a rock.

Greeves’ record of reliability in slam-bang cross-country competition establishes Greeves quality beyond question. However, it is not a quality that manifests itself in slathers of glittering chrome, nor in a fancy paint job. As a matter of fact, most of the bits on the Greeves are entirely innocent of either chrome or paint that does anything more than cover the naked metal. The steel fenders are chromed, as are the control levers, air-cleaner cover, and one little section of exhaust pipe; that was about all. The tank (steel), handlebars, muffler and pipe, and assorted other items were done in a particularly lusterless and unattractive “silver” paint.

But, there was real quality where it counts. The bike has, for example, a really effective air cleaner, and this will do more for reliability than all the beautiful paint in the world. A very neat touch that is a regular feature on Greeves motorcycles and seldom seen elsewhere is an adjustable chain-oiler built right into the rear suspension’s swing arm. You pour oil into a filler opening in the forward end of the left-side arm, and adjust the drip by means of a needle valve, also built into the swing arm, just ahead of the rear sprocket. And then there are things like the use of aircraft-type locknuts throughout. Pieces do not fall off a Greeves; you have to beat them off against something solid. That, as a matter of fact (with the rough-going capabilities), is why so many Greeves are sold. The bike may have all the style and finish of a stone axe, but it does the job. ■

GREEVES

TRAIL

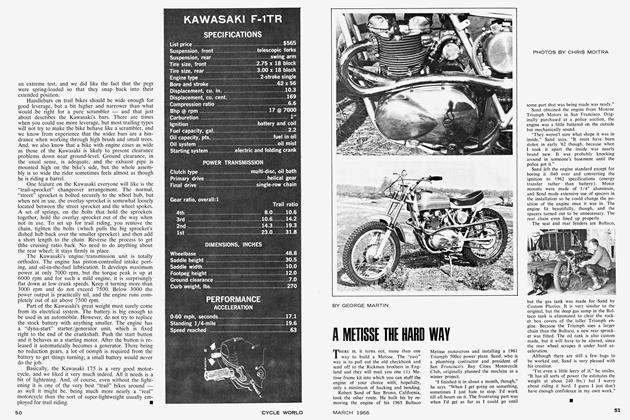

SPECIFICATIONS

$795

PERFORMANCE