TOM KIRBY

THE MAN BEHIND THE WORLD'S MOST IMMACULATE RACERS.

B. R. NICHOLLS

FAMILY MAN, useful dance band drummer, six handicap golfer after only four years at the game, and road racing enthusiast — that's Tom Kirby, and the name of Kirby is known throughout the road racing world for immaculately prepared AJS and Matchless machinery. How did it all start, and what of the man behind the machines currently ridden by Lewis Young, Paddy Driver and the 1965 discovery, Bill Ivy.

The son of a dirt track racer, it was only natural that Tom should want to go racing but any chances of going places in that sphere were ended with the outbreak of war on September 3, 1939. Although apprenticed in engineering to an Austin car agent, Tom is virtually selftaught, as the war upset his training. He returned from service life in the Far East in 1946 and two years later opened a motorcycle business, but the racing bug was not long in asserting itself; even in his latter-day service life he had managed some racing around airfield grass tracks and especially hill climbs that are such a favorite in Malaya. (At the end of hostilities the local enthusiasts literally dug up the bikes they had buried to prevent the Japanese from taking them away.)

In those early post-war days Tom's interest was grass track racing and for a couple of years he sponsored a successful local rider until taking Alf Hagon under his banner in 1951. Hagon has been winning races and National Championship titles ever since, with his peak possibly in 1958 when success was being treated in an almost blasé manner. So the partnership ended with Alf setting up his own business, doing for grass track racing what the Rickmans have done for moto-cross. Tom turned his thoughts to fresh fields and pastures new — well, not quite. It was no longer the fields of grass track, but some of the hard stuff.

Tom turned to road racing, and in 1961 a mechanic in Kirby's workshop found himself with a Matchless G-50 and AJS 7-R for the season. The rider, Ernie Wooder, as keen as they come, took the bikes to Crystal Palace and first time out won the big race of the day. That settled it, road racing was the thing for Tom Kirby. His enthusiasm is infectious and did not go unnoticed. A year later the AMC concern asked him to enter their development machinery and in 1962 this led to a stable of five 7-Rs and five G-50s, or to put it another way a brace each for his five riders. The most successful, Robin Dawson, duly obliged by winning the Junior Manx Grand Prix with a record lap into the bargain. Then Dawson retired from racing and Lewis Young took his place. In 1963 Paddy Driver and Joe Dunphy won the 1000 kilometer production race at Oulton Park on a 650cc Matchless CSR. Alan Shepherd rode a Kirby Matchless into second place in the world championship behind Hailwood's MV, and even better, beat the Gileras in a race at Mai lory Park at the end of the season. Then in November, Tom took a team to the Casablanca Grand Prix, winning the 350 race with Mike Hailwood on one of his Ajays and the 500 with Paddy Driver on a Matchless, both gaining record laps.

The 1964 season started early, for Tom was at Daytona with Phil Read and Paddy Driver riding his Matchlesses. This was one occasion where Tom's word did not go. Paddy had gotten himself a dose of the flu bug so Tom did not want him to race, but Paddy insisted that he had not flown from Johannesburg to London and then to Daytona just to watch, and flu bug or no flu bug, he was going to race. Paddy won the argument, although few people realize that after his magnificent ride into fifth place he fell off the machine in the paddock and collapsed with exhaustion. Phil finished second in that race and went on to another second in the Isle of Man in the Junior race. Then in the 500 class of the Belgian Grand Prix came possibly the best-ever results by a private team when Tom's runners were second, third and fifth, the riders being Read, Driver and Jack Findlay respectively.

However, with all this success Tom was not satisfied, nor had he been for some time. He wanted to close the gap between the AJS and foreign machines and the seed for his brainchild had been sown way back in 1962 when he saw the Morini single-cylinder 250 run so impressively against the more sophisticated opposition of the Honda four. In the venture to build the Kirby-AJS lightweight. Jack Williams was a ready and able partner on the design side, and AMC placed the race shop facilities at Tom's disposal. Jack was in charge of the project with Tom financing the endeavor.

Paper was pinned to the drawing board in July of 1963 and with the standard 7-R producing 40 bhp at 7800, an oversquare design of 81x68, compared with 75.5 x78, was decided upon. An initial aim of 45 bhp meant stronger components, for no , standard parts would stand the strain. The first practical result was a titanium connecting rod which cost $420 to be machined from solid; then came a valve spring collar at $63 and a rocker at $336. These are machining costs only. Other exotic metals are being used besides titanium but Tom is silent about these at present. The first bench test came in May of 1964 and the power curve recorded 41 bhp at 8200 with maximum revs of 8600, at which point the valves went out of control and ruined the first special piston. Tom rarely shows his disappointment and when he does it soon vanishes. "We were learning," he said with a smile as he recalled that particular incident.

The next three months were spent redesigning the valve gear and developing new pistons. At the next test in September, power went up to 42.5 bph at 8600 with a maximum of 8800, but still the valve gear was not satisfactory. Development continued and in January 1965 a further test took place and another halfhorse was found, giving 43 bhp at 8800 with maximum revs of 9200. Now was the time for a track test and it took place at Snetterton on March 1st.

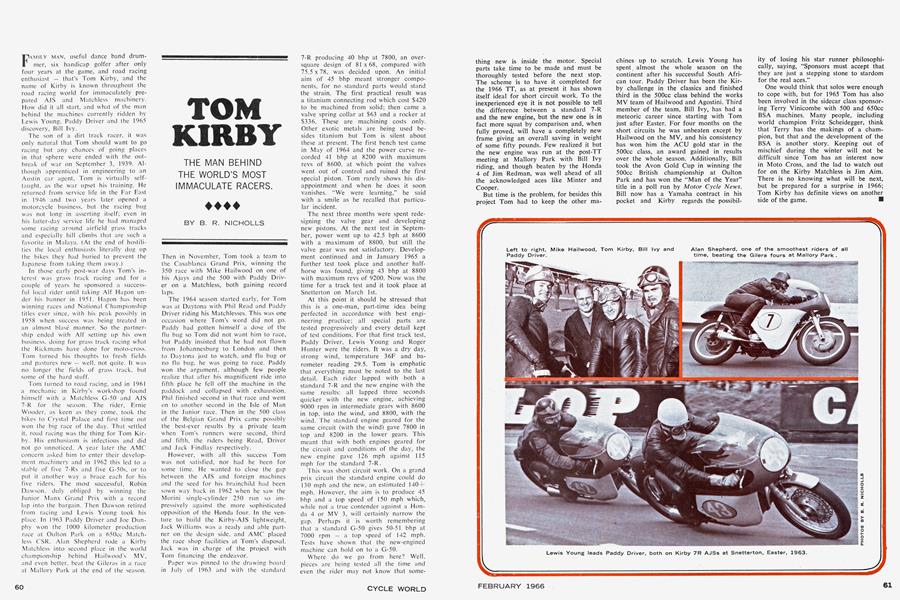

At this point it should be stressed that this is a one-man, part-time idea being perfected in accordance with best engineering practice; all special parts are tested progressively and every detail kept of test conditions. For that first track test, Paddy Driver, Lewis Young and Roger Hunter were the riders. It was a dry day, strong wind, temperature 36F and barometer reading 29.5. Tom is emphatic that everything must be noted to the last detail. Each rider lapped with both a standard 7-R and the new engine with the same results: all lapped three seconds quicker with the new engine, achieving 9000 rpm in intermediate gears with 8600 in top, into the wind, and 8800, with the wind. The standard engine geared for the same circuit (with the wind) gave 7800 in top and 8200 in the lower gears. This meant that with both engines geared for the circuit and conditions of the day, the new engine gave 126 mph against 115 mph for the standard 7-R.

This was short circuit work. On a grand prix circuit the standard engine could do 130 mph and the new, an estimated 140+ mph. However, the aim is to produce 45 bhp and a top speed of 150 mph which, while not a true contender against a Honda 4 or MV 3, will certainly narrow the gap. Perhaps it is worth remembering that a standard G-50 gives 50-51 bhp at 7000 rpm — a top speed of 142 mph. Tests have shown that the new-engined machine can hold on to a G-50.

Where do we go from here? Well, pieces are being tested all the time and even the rider may not know that something new is inside the motor. Special parts take time to be made and must be thoroughly tested before the next stop. The scheme is to have it completed for the 1966 TT, as at present it has shown itself ideal for short circuit work. To the inexperienced eye it is not possible to tell the difference between a standard 7-R and the new engine, but the new one is in fact more squat by comparison and, when fully proved, will have a completely new frame giving an overall saving in weight of some fifty pounds. Few realized it but the new engine was run at the post-TT meeting at Mallory Park with Bill Ivy riding, and though beaten by the Honda 4 of Jim Redman, was well ahead of all the acknowledged aces like Minter and Cooper.

But time is the problem, for besides this project Tom had to keep the other machines up to scratch. Lewis Young has spent almost the whole season on the continent after his successful South African tour. Paddy Driver has been the Kirby challenge in the classics and finished third in the 500cc class behind the works MV team of Hailwood and Agostini. Third member of the team, Bill Ivy, has had a meteoric career since starting with Tom just after Easter. For four months on the short circuits he was unbeaten except by Hailwood on the MV, and his consistency has won him the ACU gold star in the 500cc class, an award gained in results over the whole season. Additionally, Bill took the Avon Gold Cup in winning the 500cc British championship at Oulton Park and has won the "Man of the Year" title in a poll run by Motor Cycle News. Bill now has a Yamaha contract in his pocket and Kirby regards the possibility of losing his star runner philosophically, saying, "Sponsors must accept that they are just a stepping stone to stardom for the real aces."

One would think that solos were enough to cope with, but for 1965 Tom has also been involved in the sidecar class sponsoring Terry Vinicombe with 500 and 650cc BSA machines. Many people, including world champion Fritz Scheidegger, think that Terry has the makings of a champion, but that and the development of the BSA is another story. Keeping out of mischief during the winter will not be difficult since Tom has an interest now in Moto Cross, and the lad to watch out for on the Kirby Matchless is Jim Aim. There is no knowing what will be next, but be prepared for a surprise in 1966; Tom Kirby has definite views on another side of the game.