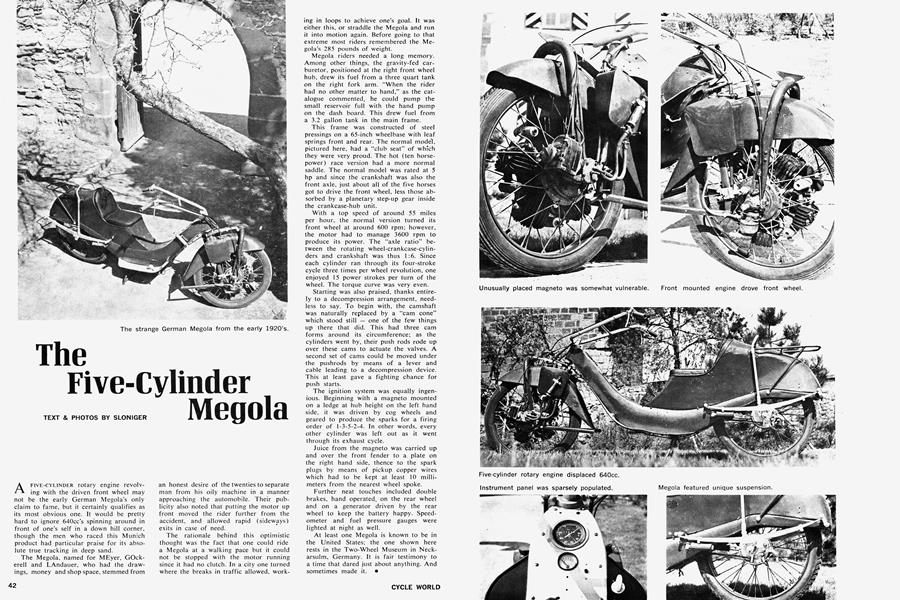

The Five-Cylinder Megola

SLONIGER

A FIVE-CYLINDER rotary engine revolving with the driven front wheel may not be the early German Megola’s only claim to fame, but it certainly qualifies as its most obvious one. It would be pretty hard to ignore 640cc’s spinning around in front of one’s self in a down hill corner, though the men who raced this Munich product had particular praise for its absolute true tracking in deep sand.

The Megola, named for MEyer, GOckerell and LAndauer, who had the drawings, money and shop space, stemmed from an honest desire of the twenties to separate man from his oily machine in a manner approaching the automobile. Their publicity also noted that putting the motor up front moved the rider further from the accident, and allowed rapid (sideways) exits in case of need.

The rationale behind this optimistic thought was the fact that one could ride a Megola at a walking pace but it could not be stopped with the motor running since it had no clutch. In a city one turned where the breaks in traffic allowed, working in loops to achieve one’s goal. It was either this, or straddle the Megola and run it into motion again. Before going to that extreme most riders remembered the Megola's 285 pounds of weight.

Megola riders needed a long memory. Among other things, the gravity-fed carburetor, positioned at the right front wheel hub, drew its fuel from a three quart tank on the right fork arm. “When the rider had no other matter to hand,” as the catalogue commented, he could pump the small reservoir full with the hand pump on the dash board. This drew fuel from a 3.2 gallon tank in the main frame.

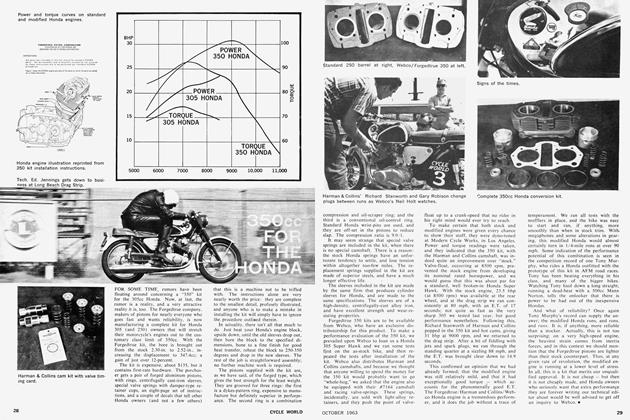

This frame was constructed of steel pressings on a 65-inch wheelbase with leaf springs front and rear. The normal model, pictured here, had a “club seat” of which they were very proud. The hot (ten horsepower) race version had a more normal saddle. The normal model was rated at 5 hp and since the crankshaft was also the front axle, just about all of the five horses got to drive the front wheel, less those absorbed by a planetary step-up gear inside the crankcase-hub unit.

With a top speed of around 55 miles per hour, the normal version turned its front wheel at around 600 rpm; however, the motor had to manage 3600 rpm to produce its power. The “axle ratio” between the rotating wheel-crankcase-cylinders and crankshaft was thus 1:6. Since each cylinder ran through its four-stroke cycle three times per wheel revolution, one enjoyed 15 power strokes per turn of the wheel. The torque curve was very even.

Starting was also praised, thanks entirely to a decompression arrangement, needless to say. To begin with, the camshaft was naturally replaced by a “cam cone” which stood still — one of the few things up there that did. This had three cam forms around its circumference; as the cylinders went by, their push rods rode up over these cams to actuate the valves. A second set of cams could be moved under the pushrods by means of a lever and cable leading to a decompression device. This at least gave a fighting chance for push starts.

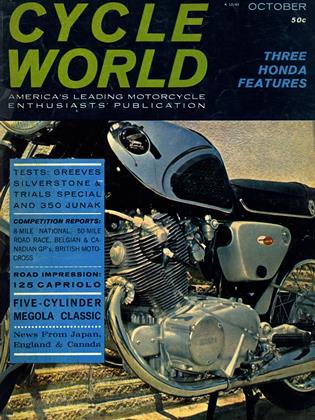

The ignition system was equally ingenious. Beginning with a magneto mounted on a ledge at hub height on the left hand side, it was driven by cog wheels and geared to produce the sparks for a firing order of 1-3-5-2-4. In other words, every other cylinder was left out as it went through its exhaust cycle.

Juice from the magneto was carried up and over the front fender to a plate on the right hand side, thence to the spark plugs by means of pickup copper wires which had to be kept at least 10 millimeters from the nearest wheel spoke.

Further neat touches included double brakes, hand operated, on the rear wheel and on a generator driven by the rear wheel to keep the battery happy. Speedometer and fuel pressure gauges were lighted at night as well.

At least one Megola is known to be in the United States; the one shown here rests in the Two-Wheel Museum in Neckarsulm, Germany. It is fair testimony to a time that dared just about anything. And sometimes made it. •