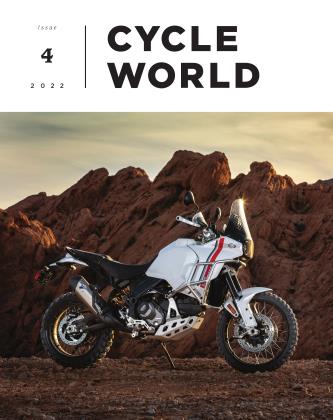

LONG BEFORE THE DESERT X

Ducati was at the heart of the Cagiva Elefant Dakar Rally winner

April 4 2022 MARK HOYER, HAMISH COOPERDucati was at the heart of the Cagiva Elefant Dakar Rally winner

April 4 2022 MARK HOYER, HAMISH COOPERLONG BEFORE THE DESERT X

Ducati was at the heart of the Cagiva Elefant Dakar Rally winner

MARK HOYER

HAMISH COOPER

It’s no secret there’s more than a waft of second-hand smoke emanating from the new Ducati DesertX’s design, particularly in the Star White Silk paint scheme with red and black accents.

The year was 1990, you could still light up a cigarette indoors in most places, and Edi Orioli rode the Lucky Explorer Elefant 900ie, a Cagiva powered by a Ducati V-twin, to victory in the 12th running of the legendary Paris-Dakar rally.

That tobacco-branded livery adorned purposeful rally-bike bodywork with twin headlights for a color-and-silhouette brain-burn that you never got over if you watched the helicopter footage or saw photos of Orioli ripping across the Senegal desert.

But even if you weren’t actually there at the time, that collective stylistic “retro” recycling and inspiration that runs every 20-30 years (check history, friends) means we’re all ripe for a new interpretation of classic rally bikes from this era.

Edi Orioli’s Dakar Rally victory was hugely significant for Cagiva and Ducati, which had spent the previous six years challenging for an overall win but never quite achieving it. In finally taking the top step of the podium, Orioli’s Elefant survived 7,500 miles, including nearly 5,000 miles of brutal competitive stages, from Paris, France, to Dakar, Senegal.

The win was a vindication of the strength of Ducati’s then-new 900cc V-twin. It was based on the 904cc twin powering the 900SS, the supersport model helping Ducati revitalize its streetbike sales under Cagiva’s ownership. It would soon be used in Ducati’s M900 Monster, which would launch a whole new motorcycle market segment and pay the bills at Ducati for a very long time.

That the engine survived Dakar was not a surprise— its lineage went back to the world championship-winning TT2 600s and FI 750s of the mid-1 980s, Orioli’s Elefant employed many technical lessons learned in long-distance racing. These included a victory at the Barcelona 24-Hour endurance race at Montjui'c Park and numerous Isle of Man TT wins, not to mention the high-speed torture test of Daytona International Speedway in support races and the actual 200-mile main event.

The Dakar race engine was actually 944cc, achieved by boring the cylinders 2mm oversize. Compression was reduced slightly from 9.2:1 to 9.0:1 to compensate for the variable quality of fuel available during the race. Cylinder head porting was standard (the 900SS engine’s factory ports had excellent flow characteristics) and valve sizes were standard 43mm intake and 38mm exhaust.

The dry clutch was also standard and ran a vented cover. The thought was the spinning plates would expel more sand and dirt than would get in and having it open would cool its operation.

Likewise, the oil capacity, at 3.7 quarts, was also standard but a much more abbreviated lower sump casting replaced the large, finned 851-type. This allowed the engine to fit better into the compact frame.

Weight savings came from magnesium engine covers (even Honda did this with its earlier XR600 Dakar single-cylinder racers). Ditching the starter motor, along with its drive gear and heavy battery, shaved several more pounds.

The six-speed gearbox of the production 900SS was swapped out for the earlier five-speed cluster, with second and third gears changed to be closer in ratio, vital to get power to the ground in highly variable conditions. The five-speed gearbox also had much wider gear teeth, making it more robust when pounded by the huge loads imposed by jumping off dunes and blasting through rocky valleys.

Barking through the Termignoni tuned, 2-into-l “open” exhaust, peak power was 66.8 hp at 8,000 rpm and maximum torque 52.1 lb.-ft. at 5,000 rpm. A standard 900SS at this time produced 72.4 hp and 55.1 lb.-ft.

The engine might have been slightly detuned for reliability but its management system gave it a huge advantage over a production 900SS. The Lucky Explorer ditched the sportbike’s Mikuni carburetors and used the Weber/Marelli ignition-fuel induction system first seen on the 851 Superbike. The rear cylinder head was reversed so the system could be installed neatly into the engine layout. The pair of 50mm 851 throttle bodies were restricted to 42mm to produce higher velocity airflow and to better match the lower maximum rpm of the two-valve 900SS cylinder heads versus the 851 fourvalve heads.

Weber/Marelli had been developing similar systems in FI car racing and Ferrari’s sports cars so the technology was at an advanced stage. Fuel management was far more precise than with carburetors, and the ignition could advance more than 50 degrees—key for smooth running at some of the lower speeds and small throttle openings required in technical off-road conditions. In a nutshell, the system ensured optimum ignition spark and fuel delivery at all times, whether the Lucky Explorer was plonking through a rocky dry creek bed or pounding over open desert at 115 mph.

While the engine didn’t look that much different from a standard 900SS, the frame was unlike anything else seen on a Ducati.

A large, curved 30mm-square box-steel backbone stretched over the V-twin engine, with beautifully machined aluminum brackets and rear suspension links. It was strong and compact with a sturdy aluminum square-section swingarm. The rear subframe was easily removed to gain access to the engine’s rear cylinder head.

Front suspension was the best Marzocchi off-road fork available with 45mm stanchions and 11.4 inches of travel and the axle mounted on the leading edge of the fork. The top-shelf Ohlins shock also provided 11.4 inches of travel.

Excel aluminum rims were 21-inchers at the front and 18-inchers at the rear (just like the new DesertX). Nissin supplied the brakes and Michelin the tires.

The bodywork included carbon fiber panels while instrumentation was secured in beautifully welded aluminum brackets. Navigation employed both aviation and Peugeot World Rally Championship technology and the hardware was returned to its maker soon after the race finished.

Overall weight was 397 pounds. Around 1 7.2 gallons of fuel was carried, adding roughly 100 pounds but giving a range of nearly 280 miles. A special pump run by the inlet-port pulse drew fuel from the lower section of the tank back up to the EFI pump inlet.

Three of these Dakar racers are known to have been built in 1990. There may have been a couple more used for testing and lead-up events to the Dakar. Around eight engines in total existed (several earmarked as backups). Two complete racebikes are still known to exist. One is in Ducati’s museum and the other in the private collection of the team that ran them in Dakar. Both feature Orioli’s race number.

Cagiva-Ducati won the Dakar with Orioli again in 1994. By this time the regulations had changed to make all racebikes closer to standard production specifications.

So the 1 990 winner marks a unique moment in Ducati and Cagiva’s history which the factory celebrated by releasing a lower-spec Elefant 900ie replica of just 999 examples.

It’s no stretch at all to call the DesertX the true successor to the Elefant, a Ducati-powered superbike of the desert.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

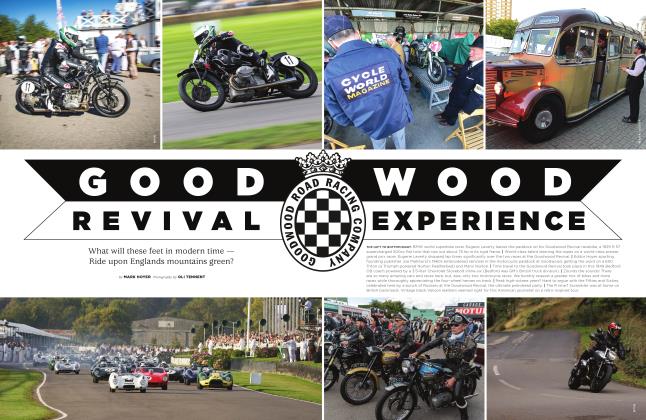

THE GOODWOOD REVIVAL EXPERIENCE

Issue 4 2022 By MARK HOYER -

DOING CIRCLES

Issue 4 2022 By SETH RICHARDS -

CONVERGENCE

Issue 4 2022 By KEVIN CAMERON -

ORIGINS

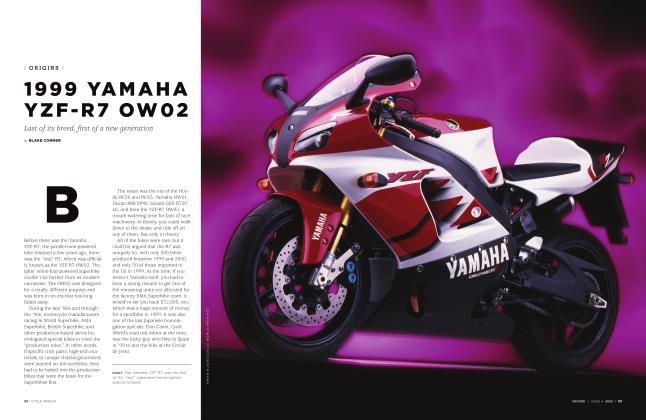

ORIGINS1999 YAMAHA YZF-R7 OW02

Issue 4 2022 By BLAKE CONNER -

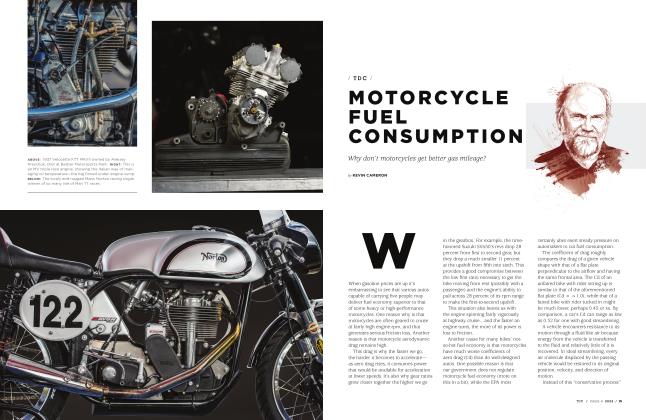

TDC

TDCMOTORCYCLE FUEL CONSUMPTION

Issue 4 2022 By KEVIN CAMERON -

The Cloud Of Control

Issue 4 2022 By SETH RICHARDS