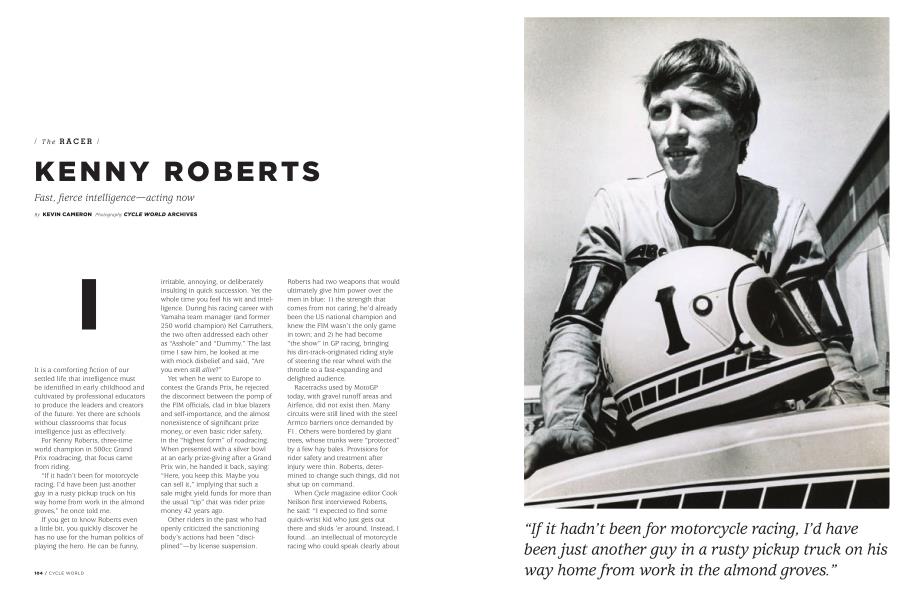

KENNY ROBERTS

The RACER

Fast, fierce intelligence—acting now

KEVIN CAMERON

It is a comforting fiction of our settled life that intelligence must be identified in early childhood and cultivated by professional educators to produce the leaders and creators of the future. Yet there are schools without classrooms that focus intelligence just as effectively.

For Kenny Roberts, three-time world champion in 500cc Grand Prix roadracing, that focus came from riding.

“If it hadn’t been for motorcycle racing, I’d have been just another guy in a rusty pickup truck on his way home from work in the almond groves,” he once told me.

If you get to know Roberts even a little bit, you quickly discover he has no use for the human politics of playing the hero. He can be funny, irritable, annoying, or deliberately insulting in quick succession. Yet the whole time you feel his wit and intelligence. During his racing career with Yamaha team manager (and former 250 world champion) Kel Carruthers, the two often addressed each other as “Asshole” and “Dummy.” The last time I saw him, he looked at me with mock disbelief and said, “Are you even still alive?”

Yet when he went to Europe to contest the Grands Prix, he rejected the disconnect between the pomp of the FIM officials, clad in blue blazers and self-importance, and the almost nonexistence of significant prize money, or even basic rider safety, in the “highest form” of roadracing. When presented with a silver bowl at an early prize-giving after a Grand Prix win, he handed it back, saying: “Here, you keep this. Maybe you can sell it,” implying that such a sale might yield funds for more than the usual “tip” that was rider prize money 42 years ago.

Other riders in the past who had openly criticized the sanctioning body’s actions had been “disciplined”—by license suspension. Roberts had two weapons that would ultimately give him power over the men in blue: 1) the strength that comes from not caring; he’d already been the US national champion and knew the FIM wasn’t the only game in town; and 2) he had become “the show” in GP racing, bringing his dirt-track-originated riding style of steering the rear wheel with the throttle to a fast-expanding and delighted audience.

Racetracks used by MotoGP today, with gravel runoff areas and Airfence, did not exist then. Many circuits were still lined with the steel Armco barriers once demanded by FI. Others were bordered by giant trees, whose trunks were “protected” by a few hay bales. Provisions for rider safety and treatment after injury were thin. Roberts, determined to change such things, did not shut up on command.

When Cycle magazine editor Cook Neilson first interviewed Roberts, he said: “I expected to find some quick-wrist kid who just gets out there and skids ’er around. Instead, I found...an intellectual of motorcycle racing who could speak clearly about exactly what he was doing and how it worked.”

“If it hadn’t been for motorcycle racing, I’d have been just another guy in a rusty pickup truck on his way home from work in the almond groves."

In 1980, when I went to interview Roberts at his home in Modesto, California, I sat a moment in my rental car, considering the tools of my trade—notebook and tape recorder. I left them on the seat. What I wanted was a conversation.

Once we were settled in a quiet room, I asked him, “How long were you in top-level motorcycle racing before you realized you were more intelligent than others around you?”

Then he told me the most remarkable things. Of being desperate at the 1974 English Trans-Atlantic Match races with a third-best practice time and no idea of how to hx it. He was already US national champion then. Needing to be alone, he made a hidden space in the Goodyear truck. After a time, he found he could play back in his mind, “almost like frame by frame,” what his British rivals were doing. Gradually—over a period of three hours—he came to understand what they knew how to do that he did not. He understood why it was working, and how he could do better.

Here an essential point must be made. It is one thing to understand and know what you must do. It is quite another to make it work—to invisibly reweave that understanding into your style and turn it into lap time. Many a rider, tempted by the beginner syndrome of rushing corners, has been told how to do better. A few have been able to make it work in practice, but in the rush of racing itself have reverted to their own natural style and slowed back down. This list includes some important champions. But hardly any are able to race from sheet music that they’ve just written.

Roberts came out of the truck, Carruthers put the chosen tires on the bike, and in three laps he was on the lap record.

“That was the first time in my life that I realized that lap times were coming from my brain and not from my wrist.”

Because it had worked so well, he went back up in the truck again.

When the FIM refused to budge on operational and organizational changes that had been urgently needed for years, Roberts joined forces with Manchester Guardian motorsports writer Barry Coleman to create a new and forward-thinking racing organization—the World Series.

As the FIM blustered, Roberts and company busily set about signing up racetracks and sponsors.

I suspect in hindsight that the FIM then realized that motorcycle GP racing had become a valuable property, and that powerful people who knew this might actually take it from them.

Roberts was a plausible threat because in every race he was showing his willingness to put everything into success. He had taken on and defeated media sensation and 1976-77 500cc World Champion Barry Sheene, the fast-talking Cockney who had taken the microphones so often shoved in his face and by his fast and witty repartee made GP bike racing into the most talked about of sports, and a favorite venue of the beautiful people.

Faced with these threats from the future, the FIM released its fixation on 1920s attitudes and made changes. Roberts accomplished that by throwing all the power that success in racing had given him into forcing the FIM to give riders their share. Like pitching it into a corner and trusting the front will hold.

Those who know him know that when he doesn’t like the company he will say breathtakingly un-PC things that some folk just can’t accept. I’ve seen it. When a particularly tiresome hanger-on at Laguna one year made a bore of himself, Roberts switched to what I think of as “Modesto mode,” and the unwanted person melted away.

And if right-thinkers don’t like it? The air forces of the world face a similar problem—which would they prefer? A smooth Kiwanis talker with good hair who can spearhead the bond drive? Or a pilot who has proved that when he goes up, enemy aircraft come down? In the first case, what you need is an actor. In the second, you need action.

After his retirement as a rider, at first Roberts ran a GP team of factory Yamahas. In the process, he attracted a group of get-it-done-today technical men whose ambition was to carry out the R&D that they felt was lacking. One of them was pipe-and-cylinder experimentalist Bud Aksland. Another was Mike Sinclair, and the third was the late Warren Willing.

It was natural that such an experienced and dissatisfied group would inevitably design its own GP bike—in this case, a two-stroke triple based on what looked like a loophole in the rules, a weight break.

The details aren’t as important as the lesson, which is that total commitment and intelligence cannot unlock every door. Sometimes in life there is no substitute for stateof-the-art R&D resources that only the overdogs can deliver. After two redesigns, the KR triple set pole at the last race of the 500cc two-stroke formula. Then it was a mad race to build their own V-5 four-stroke for MotoGP, based on combustion-chamber insights from Rob Muzzy and finance from a Southeast Asian captain of industry, who by chance had been one of Roberts’ golf partners.

It was fun while it lasted, but as Aksland put it: “I don’t mind putting in an all-nighter now and then— that’s part of racing. But I don’t want to just live in a crisis.”

After the passage of time, Roberts can be forthright about things that were once most secret, revealing that racing success often had to begin with big gambles, like sawing off the steering head of an ill-handling bike and welding it back at a different angle. (“How’s it look? OK? I’ll tack it there.”) Or stripping off the cylinders of a precious multimilliondollar prototype and machining them to alter performance. Because Roberts knew on the track what was wrong, and with that knowledge he and Carruthers had done what needed doing. Experience, knowledge, intelligence, and willingness to commit to action now.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

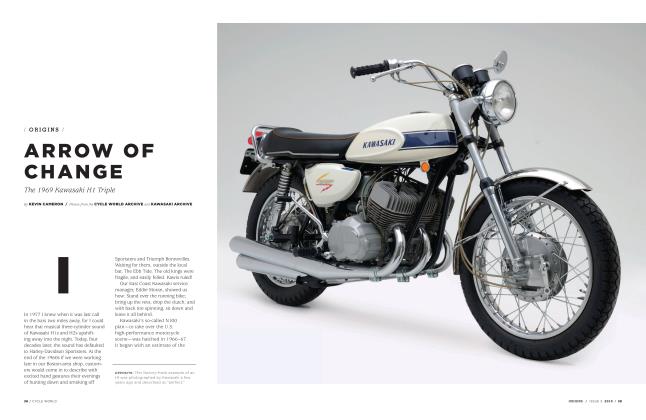

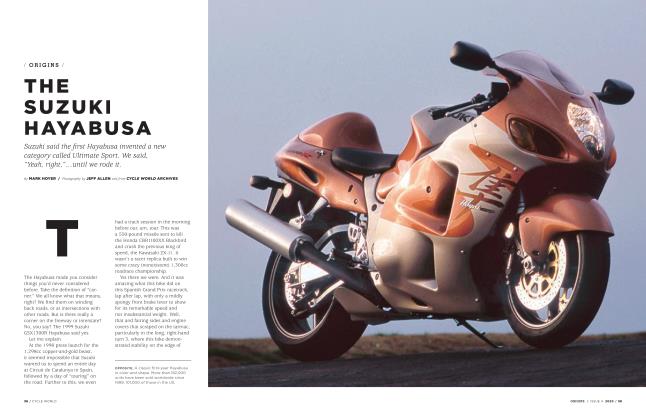

ORIGINS

ORIGINSTHE SUZUKI HAYABUSA

Issue 4 2020 By Mark Hoyer -

Features

FeaturesLittle Hero

Issue 4 2020 By Mark Hoyer -

Feature

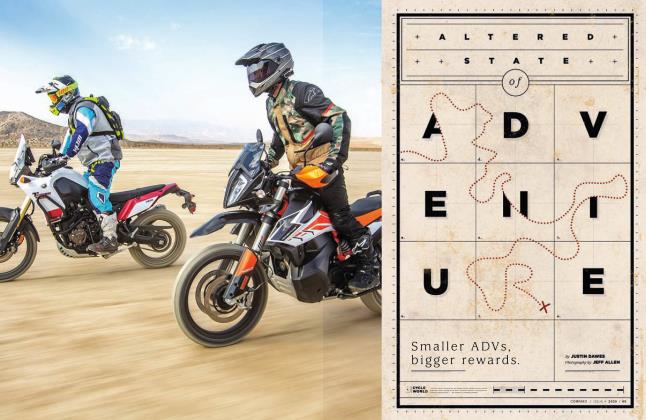

FeatureALTERED STATE of ADVENTURE

Issue 4 2020 By JUSTIN DAWES -

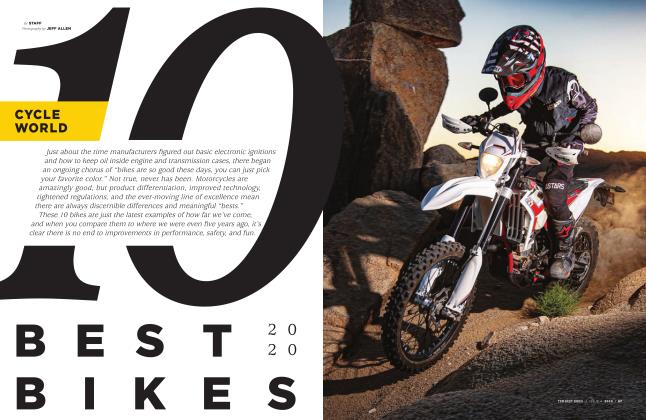

2020 10 BEST BIKES

Issue 4 2020 By STAFF, Michael Gilbert, Mark Hoyer3 more ... -

ADDING A DIMENSION

Issue 4 2020 By SAM SMITH -

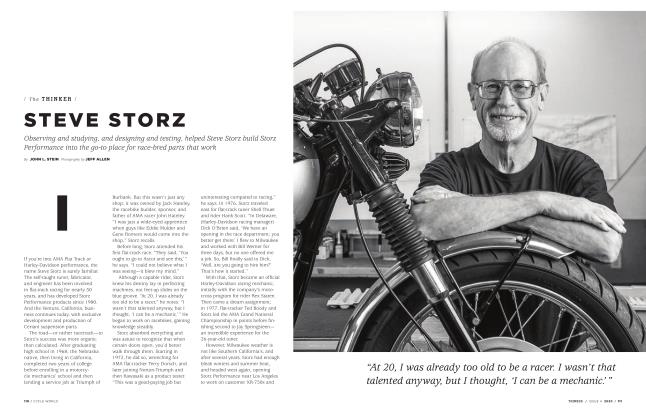

The THINKER

The THINKERSTEVE STORZ

Issue 4 2020 By JOHN L. STEIN