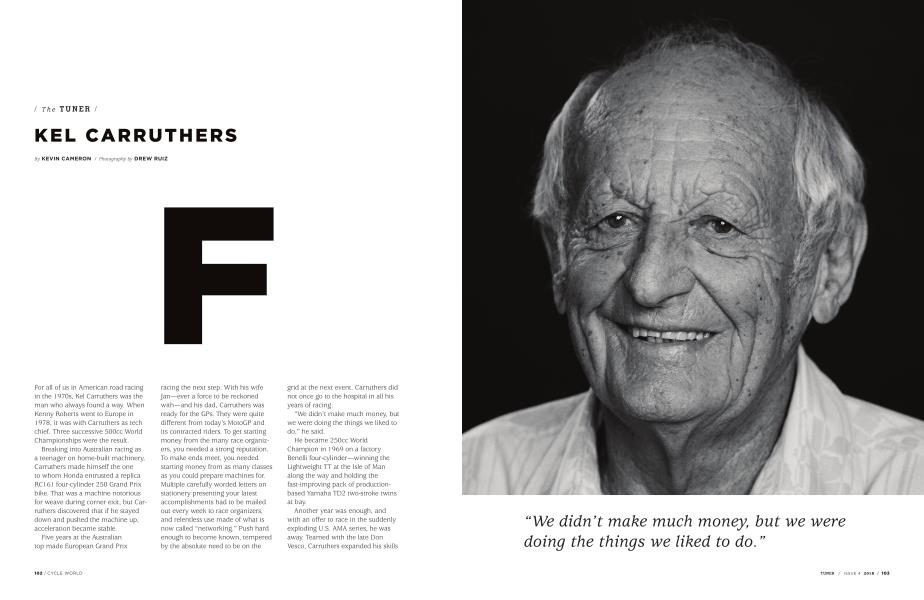

KEL CARRUTHERS

The TUNER

KEVIN CAMERON

For all of us in American road racing in the 1970s, Kel Carruthers was the man who always found a way. When Kenny Roberts went to Europe in 1978, it was with Carruthers as tech chief. Three successive 500cc World Championships were the result.

Breaking into Australian racing as a teenager on home-built machinery, Carruthers made himself the one to whom Honda entrusted a replica RC 161 four-cylinder 250 Grand Prix bike. That was a machine notorious for weave during corner exit, but Carruthers discovered that if he stayed down and pushed the machine up, acceleration became stable.

Five years at the Australian top made European Grand Prix racing the next step. With his wife Jan—ever a force to be reckoned with—and his dad, Carruthers was ready for the GPs. They were quite different from today’s MotoGP and its contracted riders. To get starting money from the many race organizers, you needed a strong reputation. To make ends meet, you needed starting money from as many classes as you could prepare machines for. Multiple carefully worded letters on stationery presenting your latest accomplishments had to be mailed out every week to race organizers, and relentless use made of what is now called “networking.” Push hard enough to become known, tempered by the absolute need to be on the grid at the next event. Carruthers did not once go to the hospital in all his years of racing.

“We didn’t make much money, but we were doing the things we liked to do,” he said.

He became 250cc World Champion in 1969 on a factory Benelli four-cylinder—winning the Lightweight TT at the Isle of Man along the way and holding the fast-improving pack of productionbased Yamaha TD2 two-stroke twins at bay.

Another year was enough, and with an offer to race in the suddenly exploding U.S. AMA series, he was away. Teamed with the late Don Vesco, Carruthers expanded his skills to include two-strokes. “Vesco had a crude little dyno. I built a singlecylinder test engine and just started finding out stuff. And my last year in Europe, I’d been on Yamahas.”

“We didn’t make much money; but we were doing the things we liked to do. ”

That rig enabled him to greatly boost the TR2’s power by extending its secondary transfers all the way down to the crankcase (as on the 250 TD2), leaving so little sealing surface that he had to run copper base gaskets. He also moved the 350’s engine forward to improve stability.

He won the U.S. AMA 250cc title and gave Yamaha its first-ever big class win, beating all the 750cc four-strokes at Road Atlanta on the light 350cc twin. Yamaha U.S. signed him for 1972—not only to ride, but also to be mentor to the emerging Kenny Roberts.

What happened next made his riding almost incidental: Carruthers was good at finding ways to get the best from Yamahas, so when the four-cylinder TZ750A was developed along with a similar 500cc GP bike, Carruthers—now manager of Yamaha’s U.S. race team—was summoned to Japan to evaluate it. It weaved at high speed. Carruthers fixed it with a longer swingarm.

In the hands of Giacomo Agostini, the new four-cylinder won Daytona at the first try (1974), but its pipes, made into flattened ovals to fit under the frame, blew to pieces during the race. Carruthers had already built the answer: round pipes, routed three under the engine and one across behind the four carburetors. They were put into production.

When Roberts famously won the AMA’s Indy Mile in 1975 on a TZ750-powered dirt-tracker, Carruthers was builder and tuner.

When a Kawasaki KR-250 set pole for the 1976 Daytona 250cc race, Carruthers almost casually raised the exhaust ports and shortened the pipes 20mm on Roberts’ Yamaha. The Kawasaki threat melted away.

At Talladega in 1974, Don Castro’s factory 750A threw his feet right off the pegs past start-finish; the weave was back. All Saturday morning, Carruthers had the bikes up on work stands with their front ends off. When they went back together, they went straight; he’d found a problem with a locating clip.

At a later breakfast after the race (another Yamaha 1-2-3), he said: “With 750s, it looks like we’ll need to put just as much work into chassis as into engines. If not more.”

So it turned out as Roberts went to Europe to race 500cc GP two-strokes. MotoGP engines have become just black boxes, while chassis remain the center of development.

Yamaha could design and manufacture, but they needed a trackside engineer who could solve problems in the moment—not make a study and publish a report in six months.

“Kel-san, please fix” became a common response to trackside problems.

In Europe with Roberts, Carruthers continued to do things that would have gotten Yamaha’s most senior engineers fired: When Yamaha fielded its 150-horsepower OW-54 square-four in 1981, Roberts said: “It feels like it’s running on three. If this is what we have to race, we may as well go home now.”

Carruthers measured the engine and saw Yamaha had given in to their usual temptation: making the transfer ports too high (which takes revs off the top).

“We had a little lathe in the transporter, so I made a setup and machined a millimeter off the base of the cylinders,” Carruthers said. “Then I raised the exhaust ports a millimeter.”

The engine was transformed. Roberts won the next race— Hockenheim in Germany. In another season, when a chassis needed a steering-head angle outside its range of adjustment, Carruthers sawed it off the bike, changed the angle, and welded it back on. He had the certainty of practical experience: You do what the situation tells you to do. When laptops arrived, he provoked much frowning among the engineers by making a spreadsheet for test results, tapping in all the data as it was gathered. After a year he was told, “OK, you can use.”

He had become racing’s indispensable man.

“Kel-san, please fix” became a common response to trackside problems. But Yamaha was learning rapidly through the 1980s, such that one day Carruthers surprised us all by saying, “I’m just a parts changer now.”

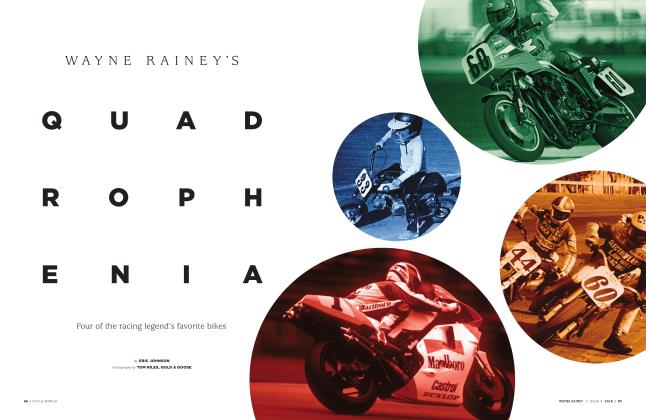

In addition to the three 500cc world championships with Roberts, he’d also tuned him to a pair of Grand National Championships in 1973-’74 and a Formula 750 championship in 1977. He was crew chief for Eddie Lawson’s 500cc world championships in 1984, ’86, and ’88, and Wayne Rainey’s three championships 1990-’92.

His last year as a GP team tech manager was 1995. The years following found him applying his two-stroke understanding to personal watercraft racing and to motocross with much success.

He is 80 well-lived, creative years old this year.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

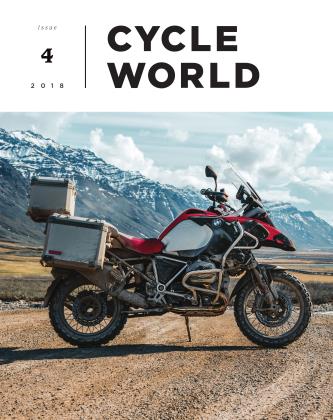

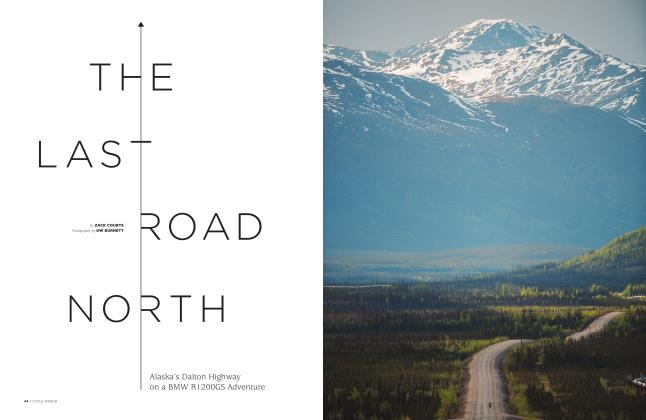

The Last Road North

Issue 4 2018 By Zack Courts -

3 Leaf Clover

Issue 4 2018 By Kevin Cameron -

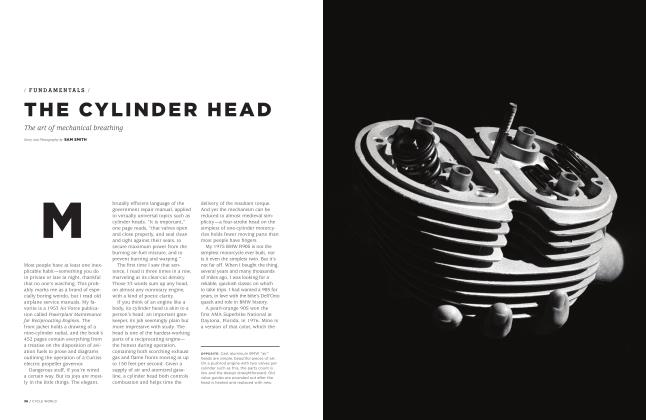

Fundamentals

FundamentalsThe Cylinder Head

Issue 4 2018 By Sam Smith -

Wayne Rainey's Quad Roph Enia

Issue 4 2018 By Eric Johnson -

TDC

TDCWhat's Shakin'?

Issue 4 2018 By Kevin Cameron -

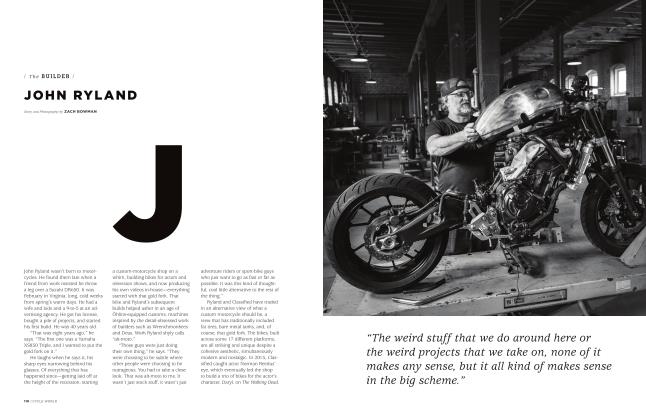

The Builder

The BuilderJohn Ryland

Issue 4 2018 By Zach Bowman