Doubling Front-End Grip and Defying Expectations

August 1 2018 Ari HenningLET IT LEAN

Doubling Front-End Grip and Defying Expectations

ARI HENNING

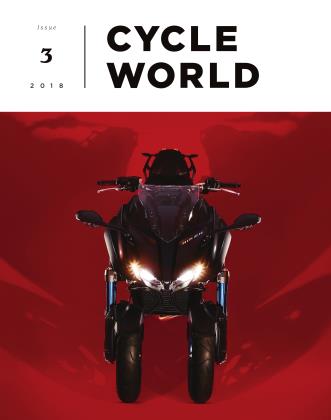

The Niken does a lot of things, but perhaps what it does best is defy expectations. Contrary to what you might be thinking, the Niken is not for beginners. It doesn’t balance on its own. It is surprisingly conventional, natural-feeling, and fun to ride. And rather than being the answer to a question that nobody asked, it’s the product of a decade-long quest to build a motorcycle with “unprecedented front-end grip.”

Yamaha didn’t necessarily expect to end up with a three-wheeler. “It was never Yamaha’s plan to come out with this design,” remarked Yamaha Europe’s motorcycle product manager Leon Oosterhof at the Niken press launch in Kitzbuhel, Austria. “We were simply pursuing the goal of increasing cornering performance by increasing front grip, to improve the riding experience when conditions are imperfect.” As a guy who feels a little anxious bending a bike into a wet corner, that sounds appealing.

Adding another front wheel was how Yamaha’s engineers met their traction goal, but they tried numerous configurations along the way. The leaning, four-wheeled Tesseract concept displayed at the 2007 EICMA show was the first evidence of Yamaha’s LMW (Leaning Multi-Wheel) program, which began years earlier and has been at a low boil ever since. Other milestones for the back-burner initiative include the 01 GEN concept and the three-wheeled 125cc Tricity scooter that was launched in Europe and Asia in 2014.

And now Yamaha is confident enough in the merits of the LMW idea to bring a full-size model to market. The Niken is essentially an FJ-09 with a two-wheeled front end. From the headstock back, things are conventional— you’re looking at a new tubular-steel frame holding an 847cc triple with a slightly heavier crankshaft; a longer aluminum swingarm; a lower, larger seat; the switchgear and dash from the MT-10; and a wider, higher handlebar that’s several inches closer to your lap.

ENGINE: 847CC INLINE THREE CYLINDER

WEIGHT: 580 POUNDS WET

LEAN: FRONT-END DESIGN ALLOWS 45-DEGREE ANGLE

OUTPUT: ESTIMATED 105 REAR-WHEEL HORSEPOWER

CHASSIS: CHASSIS FEATURES 20-DEGREE RAKE AND 74MM TRAIL

In front of that handlebar, things get strange. Under an expanse of curving fairing plastic is an arrangement of linkages and pivots that put two wheels on the road and allow the Niken to lean (up to 45 degrees) and steer like a normal two-wheeler.

Side-to-side inclination is accomplished with a stacked set of massive, transverse cast-aluminum links that keep the wheels aligned in the vertical plane as the bike leans. At either end of the parallel links, secondary headstocks angled just 20 degrees from vertical-hold tandem fork tubes that support cantilevered 15-inch wheels with 265.5mm brake discs and four-piston calipers. The rear fork tube is 43mm, and contains a spring and compression and rebound circuitry, which is adjustable. The 41mm front tube is empty and simply adds rigidity. Both columns are mounted outboard the wheels for maximum articulation.

Steering input is transferred from the handlebar to a tie-rod at a 1:1 ratio, and offset end links ensure the inner wheel follows a slightly tighter arc than the outer wheel while cornering, thereby avoiding scrubbing that would accelerate tire wear and inhibit good handling. In the end, there’s an additional 100 pounds of hardware and nearly 100 percent more rubber used to steer and support the front of the bike. The wheels reside just 410mm (about 16 inches) apart, with their contact patches trailing a mere 74mm behind the steering axes.

The Niken’s linkage design, aggressive steering geometry, 50/50 laden-weight distribution, and wheel size were all chosen to give the bike light, natural handling. And there’s no better place to test a streetbike’s handling than in the Alps. I expected the Niken to feel foreign and steer like a chopper, but as I rode up the narrow ribbon of asphalt toward the 8,200-foot Grossglockner Pass, I recognized that I probably wouldn’t have known the Niken had an unconventional front end without looking down at it. I was busy looking up, however, my focus split between the magnificent cascade of snowmelt tumbling down the cliff across the valley and the next hairpin apex.

There is a sense that the contact patch(es) is a long way from the grips, but it’s no more peculiar than your first spin on a Telelever BMW. You still countersteer (unlike on a Can-Am Spyder or a two-wheels-in-back trike), and the Niken leans just like a two-wheeler, though there’s less of a tendency to fall in toward the apex than on a single-track machine. All the skills, habits, and muscle memory you rely on while riding on two wheels apply equally to the three wheels used here.

Even with the added mass of the front end and all those extra pivots (by my count, there are 27 additional bearings!), steering doesn’t take any more effort, at least at low speeds. In terms of balance, the Niken is rock-solid stable while doing figure eights in a parking lot, with the same sort of planted feel you get on a Honda Gold Wing or Harley-Davidson Road Glide. Unlike some leaning three-wheelers, there’s no self-balancing feature or frontend lockout, so if you don’t extend the sidestand or put a foot down at stops, you’re going to have 580 pounds of motorcycle to pick up.

Once you start slicing through corners on the Niken, what stands out is how anchored that extra contact patch makes the front end feel. It’s on rails, even over cold, wet, dirty, or uneven surfaces as one might encounter in the Alps in spring. It’s a strange and exciting experience to ignore road conditions, but on the Niken, that becomes the norm thanks to the redundant traction provided by dual-contact patches.

With two front wheels, the expectation is that the Niken must shed speed like it has reverse thrusters. The binders are adequate but don’t have a lot of feel, and on dry roads, the Niken doesn’t slow any better than a two-wheeler; it has more traction than is typical, not more braking hardware. However, when road conditions are poor and traction is low, you’d better believe the Niken is going to stop in less distance and with less drama than a traditional bike.

Mashing the reach-adjustable front-brake lever to simulate an emergency stop on wet pavement, the back of the bike dances as the rear tire comes off the ground and the ABS kicks in. The front wheels are independently controlled, so one wheel might be deep into the ABS while the other is gripping well. Even when that happens, the bike doesn’t swerve to one side or get unbalanced. Stability is the name of the game with the Niken.

If there’s anything that holds back the Niken on a twisty road, it’s the footpegs touching down. They kiss the pavement at 43 degrees of lean, just 2 degrees before the parallel linkage bottoms, at which point you’re running wide. There’s also no getting around the fact that the Niken is heavy and has a fairly long wheelbase. The wide bar helps keep steering light, but once you begin making quick direction while the wheels are spinning at high speed, the Niken is less nimble.

The significant added weight (both on the chassis and on the crankshaft) stunts the performance of the threecylinder engine as well. Even so, it’s still a torquey and dynamic motor that’s made even more exciting thanks to a standard quickshifter.

On top of the fact that the Niken is fun to ride, it’s also got a comfy seat and upright ergos, and the ride quality is sport-tourer plush. I was concerned about how the dual front wheels would cope with rough roads and expected the bike to pitch sideways if one wheel hit a large bump, but it doesn’t. I even went so far as to put a wheel up on a curb and ride parallel to it. The front-end linkage let one wheel ride 4 inches higher than the other, while the chassis remained perpendicular to the ground.

That the Niken offers a genuine riding experience with obvious benefits and few drawbacks was a surprise, but after riding the bike, it was a reality I had to accept. The whole “not for beginners” idea was still hard for me to swallow, though, so I brought it up with Oosterhof.

“If it were for beginners, we’d have a different design altogether. It would be smaller, with perhaps an automatic transmission, a wider stance, and tilt lock.” Instead, the Niken has 105-ish horsepower, a quickshifter, and it’ll fall over if you don’t keep it balanced. Of course, it has safety features such as TC (that you can turn off) and ABS (that you can’t), but those features are status quo these days.

Pushing the topic further, I posited that the Niken is just a Tricity scooter on steroids. Oosterhof anticipated that comparison. “So does that mean a Ford Fiesta is the same as a Mustang? The Tricity and Niken have three wheels and lean. Both Fords have four wheels and a steering wheel, but they’re designed for very different purposes and drivers.”

Furthermore, the narrow stance of the front wheels means the Niken is classified as a motorcycle in Europe and America, so you’ll need a motorcycle license to ride it. There’s also the fact that when the Niken comes to the States in late 2018, it'll likely cost around $16,000. That’s certainly not a beginner-friendly price. According to Oosterhof, Yamaha anticipates the Niken appealing to an experienced set of riders that it categorizes as either “innovation oriented,” “experience oriented,” or “function oriented.”

Whoever buys the Niken, they'll likely enjoy it. It’s totally natural to ride, sporty enough to thrill, comfortable enough to tour on (Yamaha doesn’t have saddlebags listed as an accessory yet, but they’re surely coming), and the benefits of that added front-end traction are impossible to argue with. You might be turned off by the price or the potential maintenance on all those linkage bearings, but if you knock the Niken simply because it has a third wheel, you’re letting your preconceptions get the best of you. After all, if there’s one thing this bike is good at, it’s defying expectations.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

The Exhibitionists

Issue 3 2018 By Paul d’Orléans -

Rock Launch

Issue 3 2018 By Steve Anderson -

Origins

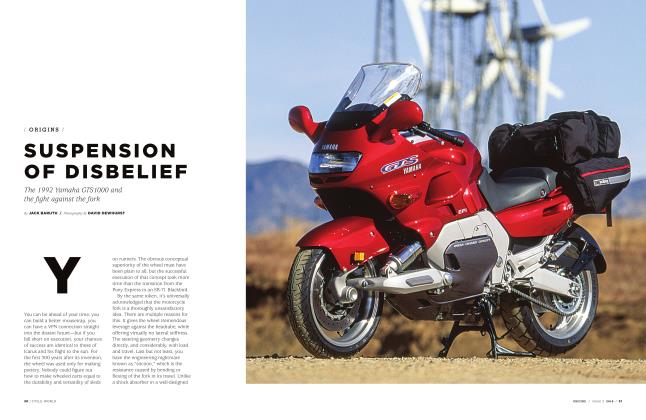

OriginsSuspension of Disbelief

Issue 3 2018 By Jack Baruth -

TDC

TDCStrange Partners

Issue 3 2018 By Kevin Cameron -

Elements

ElementsThe Workhorse

Issue 3 2018 By Kevin Cameron -

Fundamentals

FundamentalsExhausting Design

Issue 3 2018 By Kevin Cameron