THE DARK RIDER

IGNITION

WANDERING EYE

A HISTORY OF THE MOTORCYCLE AS A MENACE...

PAUL D’ORLEANS

Want a random sampling of public opinion regarding motorcycles? Tell a nonrider or non-motorcycle enthusiast that you make your living from two wheels. Their response will speak volumes on our PR problem; bikers are often viewed as Satan’s mechanical henchmen or as suicidally inclined.

While hardly news, the negative publicity staining bikes didn’t exist in the first half of the 20th century—the “dark rider” stereotype is a post-WWII phenomenon. Prior to that, artists were first to clock the psychological impact of motorcycles, grasping the thrill for both rider and observer. The motorcyclist as centaur, merged with a noisy machine and moving fast, was rhapsodized in 1909 by the Italian Futurists, whose unhinged odes to speed framed the motorcycle as a harbinger of the future (even though bikes of the day were slow and prone to external combustion). Poster artists from the 1920s conjured the power of a silhouetted rider as a symbol of superhuman speed. They were definitely “selling the sizzle,” as riding a 1920s bike on those rough roads was more super bumpy, and while a hot ’30s machine could do the ton, I can attest that’s an exercise in semi-aviation.

Images of moto-mounted German soldiers invading Poland and France shaded our view; the motorcycle as a psychological power object was suddenly tinged with menace. All militaries found bikes useful, and the rise of photojournalism spread images of swarthy riders armed to the teeth. There were good guys and there were bad guys, and it all depended on your country of birth.

French artist/poet/filmmaker Jean Cocteau was on hand to watch Swaziflagged bikes escorting Nazi brass, which made an impression. Cocteau was

the first to nail the demon-biker thing, casting a pair of late ’30s Indians as the transport of Death’s henchmen in his 1949 film Orphée. As Death’s escorts, the roar of their engines meant bad things were coming; the maw of Hades was open and ready for business. Somebody’s gonna die. The Indians are only glimpsed, but the effect of their sound and shadow is potent. The Dark Rider had emerged.

While Cocteau was making his film, a few disaffected ex-servicemen in the USA roared the countryside in packs, when they should have been watering the lawns of their suburban tract houses. Those few bikers were viewed with horror as an outsize threat to the American Way. When several California bike clubs decided the AMA racing outside Hollister wasn’t much fun on July 4,1947, their relatively harmless antics rolled into town for two days, and the local businesses made a wad.

A San Francisco photographer— Barney Petersen—turned up late, staged a photo of drunken Eddie Davenport aboard somebody else’s Harley, around which he’d rolled a lot of empty beer bottles. The SF Chronicle saw through the ruse, but LIFE magazine ran it full page as “Bikers Terrorize Town.” Frank Rooney wrote a fictional story for Harper’s based on that faked photo— “Cyclist’s Raid”—which was adapted into the granddaddy of all bad-boy biker flicks, The Wild One of 1953. Thus a chain of slander grew, embellished by the press, politicians, crappy movies... and bikers themselves, eager to wear the outlaw badge.

By the 1970s Harley-Davidson stopped resisting and embraced the Dark Rider as a marketing ploy, hoping a dollop of badass would counter throngs of “nicest people” buying Japanese lightweights. And with the industry playing along, it isn’t likely the fictionalized cliché will disappear anytime soon.

BY THE NUMBERS

1%

THE AMA’S APOCRYPHAL ACCOUNTING OF “BAD” BIKERS

14

YEARS

THE WILD ONE WAS BANNED IN BRITAIN

6.4

MILLION PEOPLE VIEWEDTHE FINAL EPISODE OF SONS OF ANARCHY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Ten Rest

September 2016 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

September 2016 -

Ignition

IgnitionThe Alternative Interior

September 2016 By Bradley Adams -

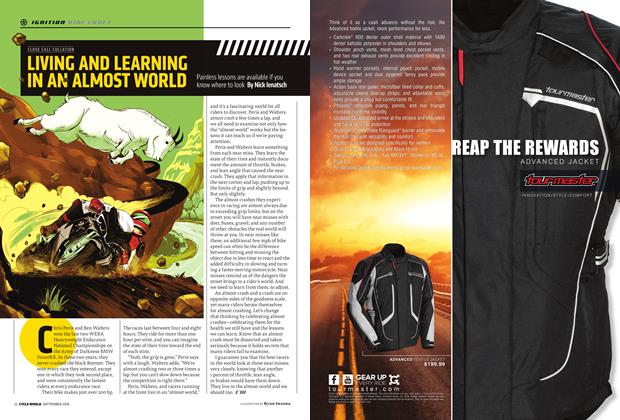

Ignition

IgnitionClose Call Collation Living And Learning In An Almost World

September 2016 By Nick Ienatsch -

Ignition

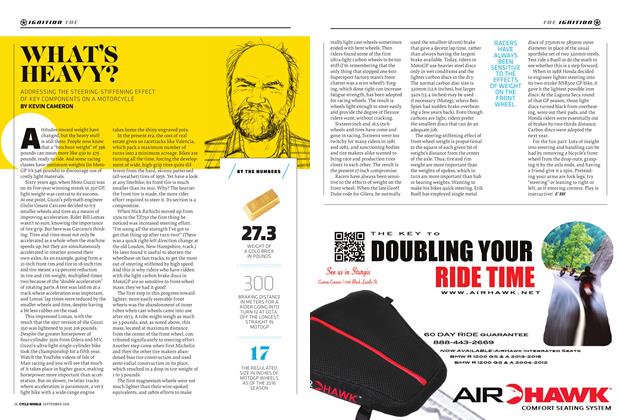

IgnitionWhat's Heavy?

September 2016 By Kevin Cameron -

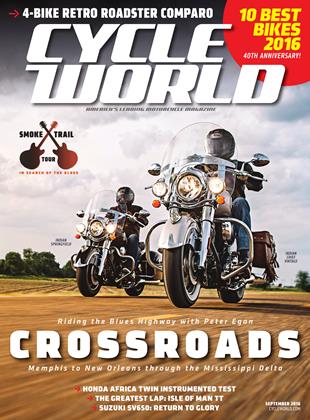

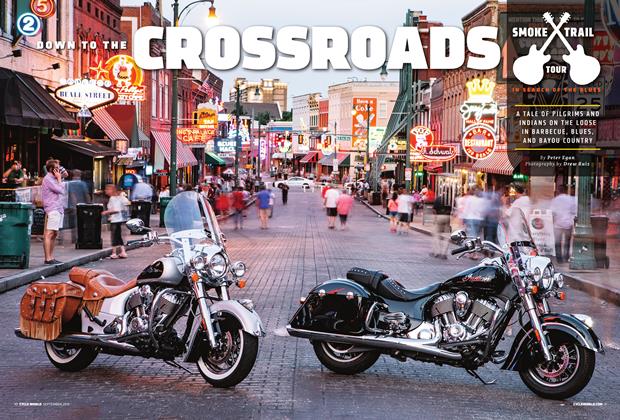

Smoke Trail Tour

Smoke Trail TourDown To the Cross Roads

September 2016 By Peter Egan