Race Watch

CAMPEONATO ESPAÑA VELOCIDAD

ma ran cu CL E BHEÉBE’S BEST RHEES EBEB rnsara

NUMERO UNO

FIM CEV

Spain’s FIM CEV is the world’s most important "domestic" roadracing series

Dennis Noyes

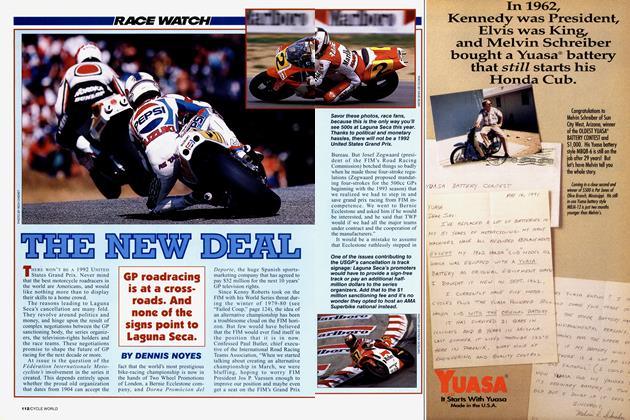

The 2014 FIM Road Racing World Championship, known generically as “MotoGP,” opened in March at Qatar with 91 riders from 20 nations filling the grids of three classes, making the 65-year-old series the second-most-international motorcycle-roadracing championship. Number one? The Spanish CEV, where—that same month at Jerez—117 riders from 23 different countries competed in Moto3, Moto2, and Superbike.

Sixteen years ago, Dorna, rights holders of the classic Grand Prix package of 125CC, 250CC, and 500CC machines, two-strokes all, reached an agreement with the Royal Spanish Motorcycle Federation (RFME) to take over that series, which, at the time, catered to three classes: 125CC, 250CC, and Supersport 6oocc. They started by streamlining the rather bulky title of Campeonato de España de Velocidad to the initials “CEV.” Dorna’s stated objectives were to professionalize, popularize, televise, and provide a national series intended to produce future GP riders while at the same time maintaining a prestigious national series. It might not be correct anymore to characterize the CEV as a domestic series. Following the example of another strong national championship, Britain’s BSB, the CEV this year for the first time held races outside its homeland. Just as BSB races in The Netherlands at Assen, the CEV will run all classes at Portimâo, Portugal, and Moto3 appeared at Le Mans as a support class for the French GP.

The CEV has even changed its name. It is now called the FIM CEV Repsol International Championship. So how international is the CEV, really? Very. More than a third of the riders accepted as full-season entries are Spanish. The most numerous contingents of non-Spanish riders come from France with nine riders, followed by Italy with eight, and Great Britain and Germany with six each. Most of the remaining nations have two or three riders. Canada, Portugal, and even Kazakhstan have a single rider.

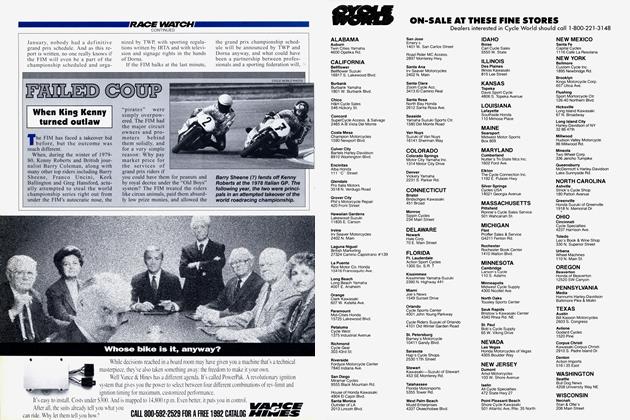

The first Americans to ride in the Dorna-organized CEV were my son, Kenny Noyes (Supersport), and Jason DiSalvo (25OCC). DiSalvo returned to the US and went on to have a strong career that continues today. Kenny stayed in Spain and went from success in the CEV to two full seasons in the Moto2 World Championship and is currently one of the top contenders for the Spanish Superbike Championship riding for the Palmeto Kawasaki team out of Madrid. Other Americans who have come to the CEV in recent years are Cameron Beaubier (125CC),

PJ Jacobson (1250c), and Dakota Mamola (1250c), Cory West (Moto2), Jake Gagne (Moto2), and the late Tommy Aquino (Moto2). The latest American to make the move to the CEV is Melissa Paris, riding in the Superstock 600 division of the Moto2/Superstock class for the Stratos team.

Coming in from abroad and beating highly motivated local riders with years of experience on the CEV tracks is a tall order, but it has been done, albeit only five times. Although forasteros (foreigners) make up 65 percent of the current fields, Spanish riders have won 40 of 45 CEV titles during the Dorna years (1998 to present). The first non-Spanish winner was AMA Pro SuperBike star Martin Cárdenas of Colombia, who won the 2004 Supersport title.

Statistics don’t tell the whole story, but these numbers don’t lie: Of the 91 riders spread over the three GP classes at Circuit of the Americas, 46 have at least half a season of CEV experience. The most international class is Moto3 (23 of 33). Moto2 is next (20 of 35), followed by MotoGP (13 of 23).

For a young rider on the way up, good results in the CEV in Moto3 or Mot02, like hitting .400 for the Toledo Mud Hens or the Lansing Lug Nuts, can result in a call from “the show,” where underperforming GP riders (or those late on personal-sponsorship payments) are sometimes changed even at midseason.

“MORE THAN ATHIRD OF THE RIDERS ACCEPTED AS FULL-SEASON ENTRIES ARE SPANISH.”

Good results in the i,ooocc Superbike class tend to be noticed more in the World Superbike paddock.

Until Dorna acquired the rights to SBK, the i,ooocc Spanish series was called “Formula Extreme” and later “Stock Extreme,” but now that SBK is a Dorna property, CEO Carmelo Ezpeleta’s idea is for CEV Superbike to become a pathway to that championship, alongside traditional sources of top SBK talent (AMA, BSB, All-Japan, Australian, German, and other national championships).

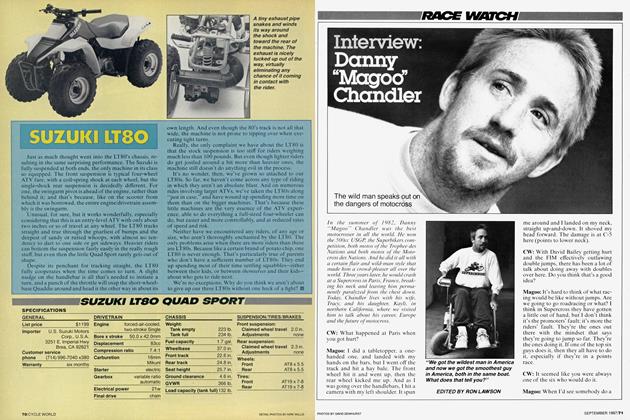

The CEV series consists of nine races for each class held on seven circuits. Each class runs doubleheader races at two of the seven venues. Five of the tracks—Jerez, Catalunya, Motorland Aragon, Valencia, and Le Mans—are homologated for FIM Grand Prix racing with curbing, curb paint, run-off room, and all garage and medical facilities kept at GP level.

Portimâo is an established SBK venue, and, since Dorna took over the production-based series, standards are now identical for both world championships. (Jerez and Motorland Aragon also host SBK races.) Albacete has hosted both SBK and World Endurance, and that track is also the scene of the annual one-race European championship. On circuits of this quality, riders usually walk away or sustain only minor injuries from even high-speed crashes.

An additional benefit of racing at Grand Prix and SBK venues is that riders moving on to world level already have valuable track knowledge at five GP tracks and three SBK tracks. CEV riders who are granted GP wildcard starts at any of these circuits also have this advantage.

Dorna’s team of race officials is composed of men and women who have worked for years in

Grand Prix racing and others who are being trained to move up. Riders meetings are held separately in Spanish and English, the two official languages.

Everything from timing and scoring to the protocol of the post-race press conferences mirrors MotoGP. After having

some problems over the years with local officials, Dorna now provides a permanent race director, technical director, and all members of race direction so that criterion does not vary from one track to the next. For the most part, corner workers have GPlevel experience.

The CEV is broadcast live on two channels in Spain: Energy TV and Movistar TV Those channels share the Dorna signal and provide their own commentary teams. This year, fans around the world in countries where no FIM CEV broadcast agreement exists can watch the races live and/or on-demand on YouTube.

Another reason the FIM CEV is a great series for overseas riders: No country on earth respects the profession of professional motorcycle roadracer as much as Spain. Unlike many nations, there is no negative connotation. The country is beautiful, people are friendly, and the weather is Southern California good.

Downsides? There is only a total prize fund of $700,000, and most riders are expected to bring personal sponsorship—anywhere from $40,000 to $150,000 and even more with some of the teams that compete in both the CEV and world championship. It is not a championship that pays big bucks and never will be as long as Dorna runs it. Dorna’s idea is that the CEV is not a destination but a training ground and departure point for riders moving on to world level.

Meanwhile, there’s a lesson to be learned in the CEV: Spain is a long way for American riders. You can’t get to Albacete from Illinois in a box van. So if there is to be a roadracing resurgence in the US, it will have to come from within.

“DORNA’S IDEAIS THAT THE CEV IS NOT A DESTINATION BUTA TRAINING GROUND AND DEPARTURE POINT FOR RIDERS MOVING ON TO WORLD LEVEL »

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

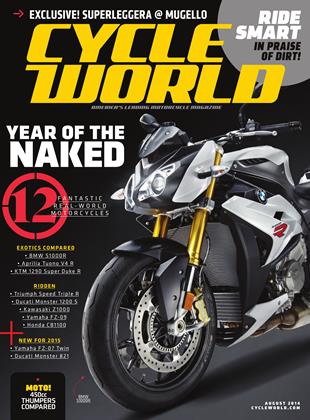

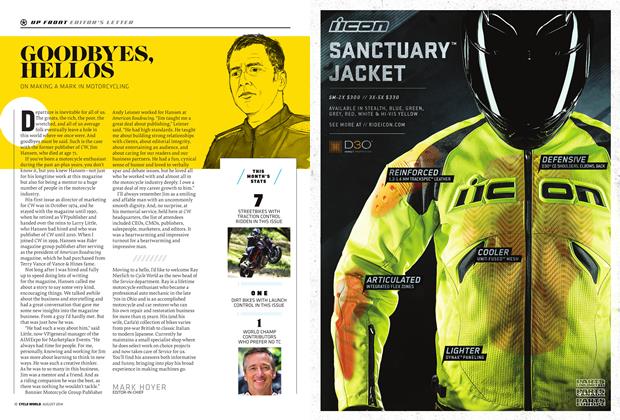

Up Front

Up FrontGoodbyes, Hellos

August 2014 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

August 2014 -

Ignition

IgnitionKawasaki Z250sl

August 2014 By Alvaro Bautista, Blake Conner -

Ignition

IgnitionCw 25 Years Ago August 1989

August 2014 By Don Canet -

Ignition

IgnitionMichelin Pilot Road 4

August 2014 By Don Canet -

Ignition

IgnitionThe Nitty Gritty In Praise of Dirt

August 2014 By John L. Stein