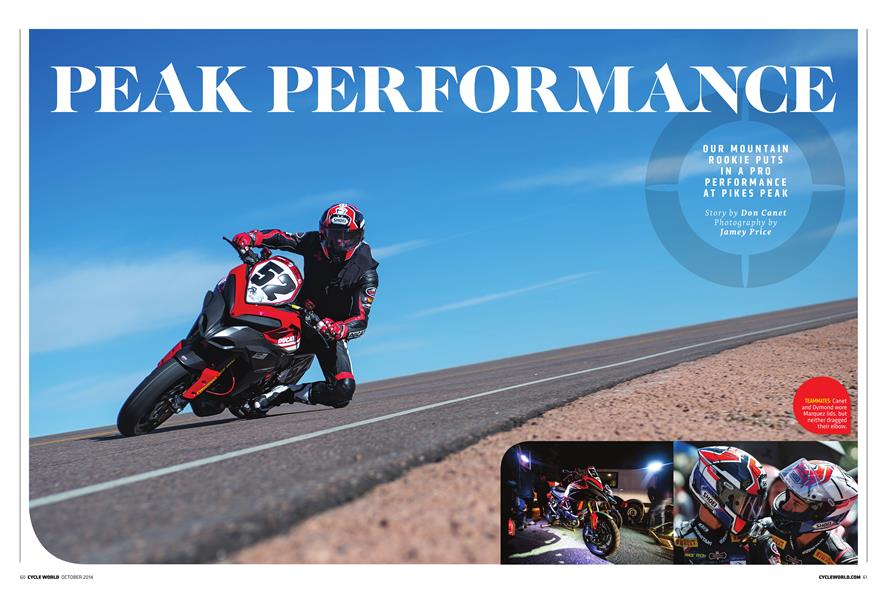

PEAK PERFORMANCE

OUR MOUNTAIN ROOKIE PUTS IN A PRO PERFORMANCE AT PIKES PEAK

Don Canet

TEAMMATES: Canet and Dymond wore Marquez lids, but neither dragged their elbow.

Like most racers, I have a list of epic racing events I want to compete in on my bucket list. Isle of Man is one of them. Suzuka 8 Hours is one. Pikes Peak International Hill Climb...wasn't one of them. Not until the whole course was paved a few years ago, anyway. Since then, I've wanted to have a go at this "real road" race in one of the most beautiful settings on earth. I finally got my chance after an email from the boss appeared on my phone: Was I interested in racing Pikes Peak?

Hell yeah!

Fast-forward to a chilly Rocky Mountain sunrise in early June. I could barely sense my fingertips as I got a maiden feel for the 156-turn, 12.42-mile Pikes Peak course at a sanctioned twoday practice held weeks prior to the event. Gripped in doubt, I questioned what I had signed up for. Never before on a motorcycle had I found such comfort in the sight of guardrail. But it seemed to me there wasn’t nearly enough steel along the edge of this barren cliff-lined road. And in one unnerving curve, a fast left aptly named “Ragged Edge,” the Armco barrier ended right about where I might need it most!

My teammate Micky Dymond—an AMA motocross and Supermoto champ, a six-year Pikes Peak veteran, and former winner—offered calm reassurance. “Don’t try to go fast too soon. Take it slow so you learn the road.” Heeding the consummate pro’s advice, I rode like there was a tomorrow, resisting the urge to push harder in an effort to keep Dymond on his number 43 bike in sight for more than a few corners.

When practice drew to a close at 8:30 a.m. to allow tourists up the mountain, shiny chicken strips remained on the Pirelli slicks fitted to my race-prepped 2014 Ducati Multistrada 1200. Just as telling, the virgin knee sliders of my Kushitani race suit had yet to kiss the cold pavement.

Following a restless night, we departed base camp at 3:15 a.m. and headed to the start area. On this day, motorcycles would practice the bottom half as race cars took to the upper portion of the course. I found confidence that morning, my desire to compete increasing with each of the half-dozen passes I made up the tree-lined section.

THE DEVIL IS IN THE DETAILS, PARTICULARLY WHEN FACING THE UNIQUE CHALLENGES OF RACING A COURSE THAT BEGINS AT 9,390 FEET ABOVE SEA LEVEL AND ASCENDS TO A 14,115-FOOT SUMMIT.

Credit my improved enthusiasm to the relaxed and methodical demeanor of the Falkner/Livingston Racing Ducati Team that took me under its wing for this adventure. There is no more experienced an outfit with which to mount a two-wheel assault on the famed International Hill Climb. The devil is in the details, particularly when facing the unique challenges of racing a course that begins at 9,390 feet above sea level and ascends to a 14,115-foot summit. The simplest things—such as learning too late that your portable generator used to power tire warmers becomes asthmatic in the thin air—have brought newcomers to their knees.

Paul and Becca Livingston, owners of Spider Grips, share a deep passion for racing with their longtime friend Rod Falkner, a former professional alpine skier and auto racer. From the outset, they imparted upon me their motivation: the pursuit of good, safe fun. Furthermore, the team abides by three principles: (1) No drama; (2) If you are late, we won’t wait; and (3) Always look professional.

The trio’s collaboration has netted multiple Pikes Peak victories and shares claim to the quickest time recorded by a motorcycle, a 9:52.819 run set by Carlin Dunne in 2012, the first year the race was held on its current all-paved surface.

As America’s second oldest race to the Indy 500, the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb is steeped in history. Motorcycles have enjoyed sporadic inclusion in what has primarily been a car race throughout the decades. Weapons of choice were dirt track and more recently supermoto bikes, but the current all-paved format now attracts new riders/drivers with roadrace hardware capable of greater speeds.

This year’s field included several literplus superbikes in our class, which was called Pikes Peak Open.

I LOST THE FRONT THREE TIMES AND THE REAR TWICE IN A FLURRY OF BOBBLES AND SAVES.

Upon my post-practice return to Colorado for the 92nd running of the Race to the Clouds, I arrived with a lofty goal of breaking the 10-minute barrier, feat that had been accomplished by only two riders. I had done my homework, committing every kink and corner to memory through a process that involved viewing onboard video footage, analyzing corner radii on Google Maps, and giving any significant turn without an official designation a name with personal significance or that pertained to a visual trackside landmark (see map).

Another huge part of our success and survival was the crew. AFi Racing, a Austin-based dealership, handled prerace prep and on-site maintenance of our Ducatis. Shop owners Jon Francis and Ed Cook headed crews assigned to each bike, which included a pair of enthusiastic US Marines provided through the VETMotorsports Wounded Warriors Project. Akrapovic importer Michael Larkin also helped as needed.

Our bikes ran stock engines equipped with sweet-sounding custom-built Akrapovic race exhausts, remapped ECUs, K&N air filters, and a modified air inlet. Each bike had a lightweight custom-fabbed subframe and compact battery, MS Production carbon-fiber bodywork, OZ Racing wheels, riser pegs, and modified foot controls, ProTaper bar, and, of course, Pikes Peak-edition Spider grips. Dymond’s machine was fitted with Race Tech-calibrated Öhlins suspension, trick Brembo front brakes from Ducati’s MotoGP team, and SICOM carbon rotors front and rear. I had stock Sachs Skyhook suspension and stock brakes biting stainless-steel Galfer Wave rotors. Traction control and ABS were not active.

Pirelli provided soft-compound Supercorsa slicks and Intermediate Wet fronts. The Wet front/rear slick setup provided excellent grip throughout the early morning practice sessions leading up to race day. Practice time was precious: just three to five runs each day on the third of the course not being used by the car groups on the other two sections.

Each section felt unique. The bottom is fast and flowing, the middle is a zigzag of point and shoot hairpins, and the fast top section becomes increasingly bumpy due to frost heaves. Skyhook’s semi-active damping continuously makes adjustments on the fly, which is supposed to help the Multistrada cope with the changing road. Nevertheless, I felt every bump and ripple!

On Friday, the final practice day, the quickest of our three runs on the bottom section established the class running order for Sunday’s race. My last run seeded me second behind Ducati i098R-mounted Frenchman Fambert Fabrice and a tick ahead of my teammate. But Jeremy Toye, perennial fast guy and a definite contender here, had crashed his Kawasaki ZX-10R superbike before laying down a truly representative time.

Following a day of rest and final bike prep, our team arrived ready to race. But “ready” might be a stretch for this rookie because, unlike any roadrace I’ve ever competed in, there was not so much as a warm-up lap. As a racer, I found this both daunting and enticing. Here at Pikes Peak, mental focus is paramount, and the gravity of this whole experience grew significantly thicker in the staging area when a severe crash (a fatality, we later learned) at the summit caused a lengthy two-hour delay.

My tire warmers finally came off once Fabrice started his run. I took the green flag at noon in much warmer conditions than we ever faced in practice.

Ease away, short-shift into second, square the first left, then pin it! The run was going to plan as I threaded the big Multistrada through a long series of medium and fast corners leading up to Engineers Corner. It was through this second-gear, left-right transition that I got a startling taste of how much the surface grip had worsened since practice. I lost the front three times and the rear twice in a flurry of bobbles and saves but managed to finally recoup my drive while powering onto the Picnic Grounds straight.

I might have been near the treeline, but I wasn’t out of the woods. Not long after, I really lost confidence in front edge grip with a quick tuck here and a push under trail-braking there. Had we chosen the wrong tire? Or had three hours on the warmers overcooked the chicken? Not the sort of thoughts one needs mid-run. I pushed on, hoping things would improve in the cooler temps at higher elevation.

But they didn’t. Altering my game plan, I took the Cove Creek left in second rather than third gear and even checked up a bit through Ragged Edge. Then, following another startling front tuck and a rear slide exiting Double Cut, I lost a ton of confidence when the rear broke loose a couple of turns later with the slightest application of throttle. Was the rear tire losing air? Associate Editor Mark Cernicky crept into my head; he’d crashed out of this race a few years ago when his rear tire lost pressure!

PIKES PEAK COURSE STATISTICS

Length:

12.42 miles Surface:

Pavement

Turns:

156

Elevation at start:

9,390 ft.

Elevation at finish:

14,115 ft.

Length of plus grade:

61,626 ft.

Maximum plus grade:

10.5 percent

Length of negative grade:

3,934 ft.

Maximum negative grade:

10.0 percent Average grade:

7 percent

At that moment, I surrendered to the mountain and motored on to the summit to finish in to minutes, 10.01 seconds. My quest to break the io-minute barrier denied. But I was third in class (and third-fastest bike overall) behind winner Toye and Fabrice, who both were shocked at how much this challenging course had changed on race day. Still, I was proud to be on the podium and to have set the nth fastest overall time, car or bike, of the day. It was the experience of a lifetime and a good reminder that you’re ultimately racing the mountain. As it has done countless times before, the mountain humbled yet another man and machine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

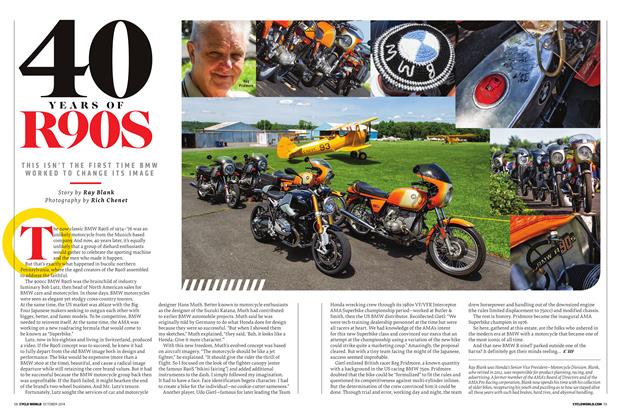

Up Front

Up FrontSit Down. Sit Up.

October 2014 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

October 2014 -

Ignition

IgnitionCw 25 Years Ago October 1989

October 2014 By Andrew Bornhop -

Ignition

IgnitionOn the Record Jonathan Rea

October 2014 By Matthew Miles -

Ignition

IgnitionAlways Be Ready Emergency Avoidance Skills

October 2014 By John L. Stein -

Ignition

IgnitionThe Great Tom Sifton

October 2014 By Kevin Cameron