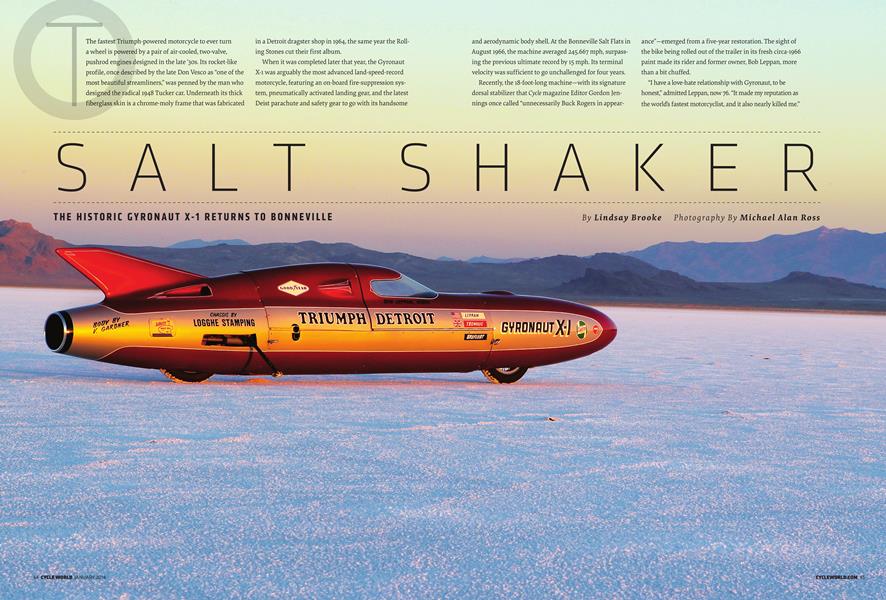

SALT SHAKER

THE HISTORIC GYRONAUT X-1 RETURNS TO BONNEVILLE

The fastest Triumph-powered motorcycle to ever turn a wheel is powered by a pair of air-cooled, two-valve, pushrod engines designed in the late ’30s. Its rocket-like profile, once described by the late Don Vesco as “one of the most beautiful streamliners,” was penned by the man who designed the radical 1948 Tucker car. Underneath its thick fiberglass skin is a chrome-moly frame that was fabricated

in a Detroit dragster shop in 1964, the same year the Rolling Stones cut their first album.

When it was completed later that year, the Gyronaut X-i was arguably the most advanced land-speed-record motorcycle, featuring an on-board fire-suppression system, pneumatically activated landing gear, and the latest Deist parachute and safety gear to go with its handsome and aerodynamic body shell. At the Bonneville Salt Flats in August 1966, the machine averaged 245.667 mph, surpass ing the previous ultimate record by 15 mph. Its terminal velocity was sufficient to go unchallenged for four years. Recently, the iS-foot-long machine-with its signature dorsal stabilizer that Cycle magazine Editor Gordon Jen nings once called "unnecessarily Buck Rogers in appearance”—emerged from a five-year restoration. The sight of the bike being rolled out of the trailer in its fresh circa-1966 paint made its rider and former owner, Bob Leppan, more than a bit chuffed.

Lindsay Brooke

“I have a love-hate relationship with Gyronaut, to be honest,” admitted Leppan, now 76. “It made my reputation as the world’s fastest motorcyclist, and it also nearly killed me.”

When under whose the assault “Big 1970 Red” Bonneville by two Yamaha other speediest fast streamliner guys. arrived, First powered Leppan’s to beat it by a pair record was Vesco, of was R3 350CC twins raised the official mark to 251.924 mph. Then came the new Harley-Davidson streamliner of Warner Riley and Denis Manning, packing a nitro-burning i,474cc Sportster engine.

With veteran Harley racer Cal Rayborn at the controls, the Milwaukee-backed beast shattered Vesco’s mark by 15 mph and raised the world record to 265.492 mph. By the time Leppan, his business partner Jim Bruflodt, and the crew from their Detroit Triumph dealership had loaded Gyronaut into their big diesel transporter and were on their way to Utah, they were already down by 20 mph.

“Vesco and Rayborn didn’t catch us completely off guard, but Jim and I figured the serious challenge wouldn’t come until 1971, when we’d have an all-new bike with twin Trident engines ready,” Leppan recalled. As a stopgap, they’d upgraded Gyronaut’s pair of 650CC twins using special 820CC kits from Sonny Routt. The four big Amal GP carburetors previously set up for methanol were now jetted for nitromethane to give about 170 hp. To further cheat the wind, the bike’s body panels were carefully finessed so that they fit precisely flush.

Right off the trailer, running a 40-percent nitro load, Gyronaut fired off consistent qualifying runs above 260 mph. One official run through the USAC speed traps was 264.437 mph. “It was running perfectly, and the handling felt great,” Leppan said. “I felt confident we could defend the record the following day.”

October 21,1970, dawned and the Triumph-Detroit crew rolled Gyronaut as far back from the starting line as possible, near to where the salt meets the entrance road. This meant Leppan had to cross a long stretch of bumpy salt starting out, but with a 170-mph first gear ratio, he wanted to get the best possible run into the measured mile. Everything went smoothly until rider and machine reached the 4-1/4-mile marker on the 9-mile course.

“Suddenly, I felt a violent speed wobble,” Leppan remembered. “The bike was still accelerating; the tach read 8,300 rpm, which, by our gearing calculations, meant in excess of 270 mph. I closed the throttle and pulled the parachute cord, but the bike was already airborne.”

Veteran USAC timer Joe Petrali and others watched Gyronaut fly 50 feet into the air, they later told Leppan. During that moment, the bike’s canopy blew off, and before the spiraling machine slammed down into the salt, Leppan’s left arm was flung outside the shell. The latest Deist arm restraints that had been designed into Gyronaut in 1964 were not installed, Leppan claims, because the tech rules didn’t allow them.

RIGHT OFF `IHE TRAILER, RUNNING A 40-PERCENT NITRO LOAD, GYRONAUT FIRED OFF CONSISTENT QUALIFYING RUNS ABOVE 260 MPH. ONE OFFICIAL RUN THROUGH THE USAC SPEED TRAPS WAS 264.437 MPH.

The 8oo-pound streamliner slid on its side for another mile, with Leppan’s left arm pinned underneath. It finally stopped at the 5-1/2mile marker, having crossed the timing lights at 264 mph.

“I should have been dead,” Leppan said. Later examination of the bike’s chassis revealed a fractured tube near the front axle support that he believes caused the front suspension to collapse, inducing the severe high-speed wobble that instantly hurled the bike into the sky.

Heroic driving by a husband-and-wife ambulance team who were there on the Flats—their Cadillac with siren wailing topped 100 mph on Interstate 80 in the frantic run to the Salt Lake City hospital—helped save Leppan’s life. He’d smashed more than 9 inches of main artery in his arm and lost many pints of blood, but, incredibly, he remained conscious through the entire 140-mile drive. When the ER doctors told Leppan that his arm would have to be amputated, he demanded to be flown to a Los Angeles hospital—the stretcher mounted across four seats on a commercial flight—where arm-saving surgery was performed 14 hours after the crash.

After a nine-week hospitalization came an intense physical rehab regimen, which included working the controls on a special handlebar built for Leppan by Triumph’s West Coast service manager, Pat Owens. Slowly, Leppan regained partial use of his hand. But despite wanting to build an all-new speed-record bike, the demands of running his dealership and family life took precedent. The mildly repaired Gyronaut X-i chassis was run one last time at a Michigan dragstrip in 1975 then partially disassembled and stored.

Thirty years later, a San Francisco-area biomedical engineer named Steve Tremulis began a quest for the legendary motorcycle his famous uncle, Alex Tremulis, had helped create in 19ó3-’64. He eventually tracked down Leppan, who helps his son, Robert, sell Ducati and other Italian motorcycle brands at their TT Motorcycles store not far from his old Triumph-Detroit shop.

“In my many conversations with Bob,” Tremulis said, “I recognized how he and

Gyronaut were intertwined, but I also sensed that he might want to let it go eventually.” Meanwhile, Leppan had decided to finally restore the machine. He outsourced the chassis to Jim Lamb and Tony Kulka at Jefferson Motor Service, who found it to be remarkably straight and intact given the wallop it endured in 1970. By the time the work was completed in 2010, Tremulis and Leppan had struck a deal, and the freshly restored rolling chassis, along with the untouched twin-engine powerpack, the incomplete body sections, and assorted Gyronautobilia (including the surviving fragments of the destroyed shell), were on their way to the Bay Area.

From there, new owner Tremulis pushed the ambitious restoration project into overdrive, aiming to get the fully restored (and hopefully running) ’liner to the 2013 Bonneville Speed Week. He enlisted New Jersey-based Rob Ida Concepts to restore the incomplete shell, which Leppan had considered the most daunting and costly step because it required construction of a new canopy and engine cover.

“I’m a fan of everything Alex Tremulis ever did,” explained Ida, a Tucker owner. “When Steve called me about this project, I had to have my hands on it! His timetable to get to the Salt Flats in late August was so aggressive, but my guys made it happen. We came in at 5 a.m. and worked until 1 or 2 the following morning. Then we’d hit it again after a few hours’ sleep.”

Using period photographs and original Alex Tremulis detail drawings as reference, and Gyronaut’s existing nose, tail, and lower body sections, Ida’s team then created a computer model of the complete shell. From that they made twodimensional templates of the canopy and engine cover and sculpted undersized 3-D panels by hand. “We laid the fiberglass over the top of that, compensating for the thickness of the material,” Ida said. There was 200 hours in the body project, including the burgundy and silver paint scheme that Gyronaut wore for its 1966 record.

To top off Ida’s masterful work, the chassis with painted shell was transported to the suburban Detroit-based custom painter who had hand-lettered and striped Gyronaut in 1965. “I never could have dreamed that I’d again be working on this machine 47 years later,” said “Wild Bill” Betz, who now specializes in yacht transoms and other high-end lettering and was delighted to again have “the great piece of speed history” under his brushes. Tremulis turned his attention to the engines, which had been dormant since 1975. He called upon vintage Triumph racing and resto specialist Jerry Liggett at Triple Tecs to freshen up the powertrain to “demonstrator run” condition. Final assembly of the bike took place, appropriately, at TT Motorcycles, where for three weeks, Leppan, his lead tech Butch Casaday, and local vintage Triumph expert John Hubbard sweated innumerable details fabricating various bits, aligning components, and timing and tuning the engines. Unfortunately, when the van arrived to take Gyronaut back to the Salt Flats, the team had perhaps two more days’ work remaining to finish the job. While the bike arrived at Bonneville as a non-runner, it delighted those who saw it on display.

Among the many Motor City friends who stopped in to see the bike at Leppan’s shop was Roy Steffey, who in 1964 was the ace fabricator at Logghe Brothers, the Michigan company that built Top Fuel dragster frames, pioneered the flip-top Funny Car, and built Gyronaut’s chassis.

“It took about a week to fab up,” Steffey recalled. “We built a fixture of sorts to jig the frame, and I heli-arc welded the 4130 tubing. It was a fairly straightforward build, but there were no formal blueprints. I had to work from sketches and some dimensions provided by Bruflodt and Tremulis. The ‘blueprint’ was in their heads, so we made changes on the fly.”

Steffey noted that because Gyronaut’s chassis is dimensioned for the smallblock Ford V-8 that Tremulis had dreamed would power his gyroscopically balanced streamliner, it’s a couple of inches wider than it needs to be for the Triumph powerpack. Leppan explained that Tremulis’ horizon-bending plan included X-2 and X-3 Gyronauts, each with greater performance. The ultimate was to be a turbine-powered bike aimed at breaking the sound barrier, though Leppan confesses it would have been tough to beat Craig Breedlove and Walt Arfons in their jet cars.

“Alex did actually convince Ford to ship him the Shelby Cobra V-8, and he eventually got a gearbox and a differential,” Leppan said. “The only items he couldn’t get were proper gyroscopes. If that had happened, who knows where the Gyronaut story would have gone.” CUM

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAmerican Renaissance

JANUARY 2014 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

JANUARY 2014 -

Ignition

IgnitionVip Lounge

JANUARY 2014 By DC -

Ignition

IgnitionCw 25 Years Ago

JANUARY 2014 By Matthew Miles -

Ignition

IgnitionNew Ideas Fresh Gear For Great Rides

JANUARY 2014 By Matthew Miles -

Ignition

IgnitionOne Step At A Time How To Coach Your Kid (or New Rider)...

JANUARY 2014 By Nick Lenatsch