Revolution of the Species

BMW’s all-new R1200GS pushes the technology and performance envelopes with careful adherence to history

MARK HOYER

A GOOD FRIEND ONCE TOLD ME HE LIKED TO HAVE HIS finger hovering over the proverbial eject button in life, even though he never had any intention of using it. The feeling it conveyed to him was that he could chuck it all at any time and somehow live “free.”

The BMW GS series has always had that element as a major part of its appeal. It’s the thought that you can ride almost anywhere, carrying just those th needed for survival and adventure—eyen if you don’t ride “almost anywhere.” Asthis trailblazing flat-Twin has evolved over the past three decades, each of the five generations has expandecfthe onand off-road capabilities oyer the previous.

CW RIDING IMPRESSION

Of the three generations I’ve experienced—R1100GS, RI 150GS and the oil-head R1200GS—the liquid-cooled 2013 model is the biggest leap of all.

It’s difficult to pick a single area that stands out as the greatest change. Certainly, liquid-cooling the Boxer engine is a huge deal (even if it’s only 35 percent liquid-cooled), but the step to semi-active suspension and the complex (yet easy to use) multiple riding modes rank up there, too.

Our first ride on the new GS was South Africa, a favorite destination BMW. This was the fourth time I’d been there with the Germans, and my third time riding an R1200GS.

South Africa is quite grand, although it doesn’t feel all that different from riding in a remote area of Nevada. But you don’t see many giraffes near Pahrump, do you?

We began in the town of George on the coast of the Indian Ocean, 270 miles east of Cape Town. We headed for the Little Karoo, a semi-arid Expanse over the mountains to the north. As fits the character of the bike, we’d hit most types of terrain on the planned ride, from rock-strewn trails (on a special

loop aboard an accessorized, knobbyequipped GS) to winding dirt roads to just about every kind of asphalt highway and byway.

While the overall design of the 2013 R1200GS emphasizes its variable-use nature, the multiple riding modes and rider aids do a, lot to expand its capabilities. We might as well get right down the electronics rabbit hole, because the systems have a huge influence on the bike’s behavior and its success on all terrain.

We’ve seen power modes, electronically adjustable suspension, selectable ABS and adjustable traction control, but the “global” pâture of wbat’s happening on our fully optioned GS makes it very easy to use.

Five riding modes (switchable on the fly) influence all the electronic rider aids: Dynamic, Road, Rain, Enduro and Enduro Pro. The first four are part of the options package, whereas Enduro Pro must be unlocked with an additional plug-in.

Each mode varies settings for the ride-by-wire “E-gas” throttle response, ABS and ASC (BMW’s traction control) intervention, as well as how the “semiactive” Dynamic ESA varies compression and rebound damping as you ride.

Choose Dynamic, for example, and throttle response gets very quick, ABS is set for the level of grip encountered on the road and ASC allows some on-throttle slip, “even enabling experienced riders to perform light drifts,” says BMW. ESA tightens up front and rear shock damping for maximum control, although the rider can still select Soft, Normal or Hard ranges within the overall Dynamic mode. Setting it to Road takes the edge off the damping and throttle settings, and ASC cuts in sooner.

Enduro, meanwhile, is optimized for riding on dirt with the standard, tarmacoriented tubeless radiais. Throttle response is quite gentle and ASC/ABS settings allow some latitude for sliding the rear using brake or throttle. Also, the ABS is in “partial integral” operation (as in street modes), meaning that application of the front brake automatically sends some braking force to the rear. ESA options are limited to Soft (default) or Hard.

Bottom line: Through a few buttonpushing operations, you can tune the response of the GS to the prevailing conditions and your riding mood. And, thanks to all the sensors at work, it also is adapting suspension damping to how you’re riding.

It’s a very good system, but it wouldn’t be effective without an excellent collection of hard parts.

Starting with the engine, the character of the new, liquid-cooled 1170cc flat-Twin is very similar to that of the previous version, only amplified. Bore and stroke are unchanged at 101.0 x 73.0mm, but almost everything else is different, from “vertical flow” cylinder heads to the wet clutch to the more compact overall dimensions. It’s a classic BMW Boxer but much snappier and harder pulling everywhere. If there is any loss, the old engine’s luggability has been diminished. Claimed output is 125 horsepower (up from 110); we expect about 115 at the rear wheel.

And while the reoriented intake and exhaust ports (top and bottom, respectively, rather than rear and front) have many technical benefits with regard to internal parts layout (see “A Cooler Boxer,” January), the rider benefits from not having intake runners and throttle bodies where his legs reside during foot-down dirt riding.

From the saddle, there is more airbox noise than I recall on the previous GS, but the flat drone of the Boxer remains. It’s not a passionate, energetic sound, even with the new-found performance (bigger valves, higher compression, new cam profiles), but it is the sound of adventure and reassuring if you’ve had any seat time on BMW horizontally opposed Twins. The engine pulls smoothly down to about 2000 rpm in top gear, and power begins to taper off at around 7500 rpm, 1500 revs before redline.

The wet slipper clutch (now located at the front of the engine) offers a pleasantly light pull and easy modulation from its four-position-adjustable lever, and the new six-speed gearbox proved to have excellent shift quality.

The free-revving nature of the engine was readily apparent as soon as I fired up the bike, but it was really noticeable when I hit the winding mountain road leaving George. Big, 90-mph sweepers were punctuated by tighter bends and long, uphill straights. Vibration from the counterbalanced engine is still characteristic BMW Twin, with a high-frequency buzz that gets more noticeable as revs climb, but it’s more of a communication that the engine is working than a knock against comfort. At lower revs, it thrums along nicely. Overall, this is a faster, smoother GS.

It also handles better. Steering geometry is slightly more aggressive with 25.5 degrees of rake and 3.9 inches of trail, while wheelbase is unchanged at 59.3 in. The steel frame and bolt-on subframe are stiffer, as are the new Telelever front and left-side-mounted EVO Paralever rear suspension. Overall, it’s a more solid-feeling platform than before, and due to the more compact engine, the swingarm is now about two inches longer. Bigger Metzeier Tourance Next tires (on wider rims) help improve grip and communication from the contact patches, while their profiles help keep the bike neutral-steering even when trail-braking hard.

Moreover, the new GS is more responsive to steering input and feels more connected to the road. It’s not “big supermoto” in the way that the Ducati Multistrada is, but it is a swift machine on a backroad.

The new Brembo Monobloc front calipers and ABS are excellent on road and off. The system has a feeling of security and performance similar to that imparted by the K1600GT/GTL.

In the dirt, working within Enduro mode’s ABS/ASC tuning parameters required very smooth application of throttle and brake. Too much of either resulted in “pumping”—the system cutting in and then releasing repeatedly. But, overall, the composure on loose surfaces was excellent. ABS and ASC can be switched off independently while in motion, allowing advanced riders more control (or less!) in any mode.

I flipped off the ABS and ASC in various riding modes to explore the “natural” degree of throttle and brake control

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBeing Prepared

APRIL 2013 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

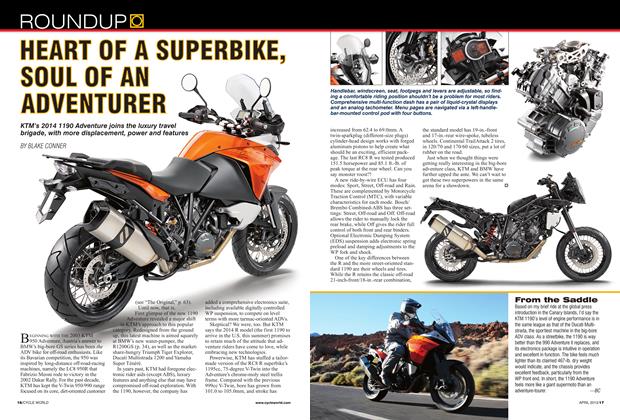

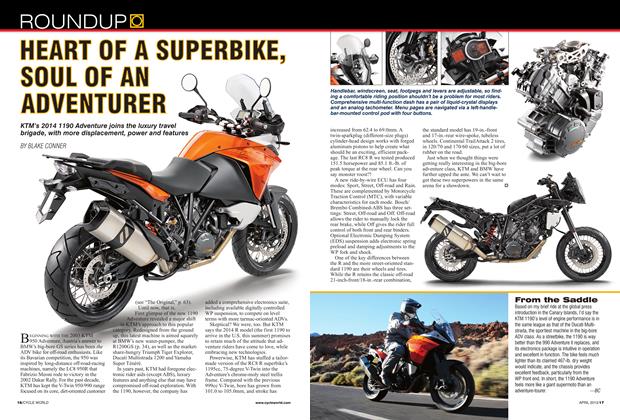

RoundupHeart of A Superbike, Soul of An Adventurer

APRIL 2013 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupFrom the Saddle

APRIL 2013 By BC -

Roundup

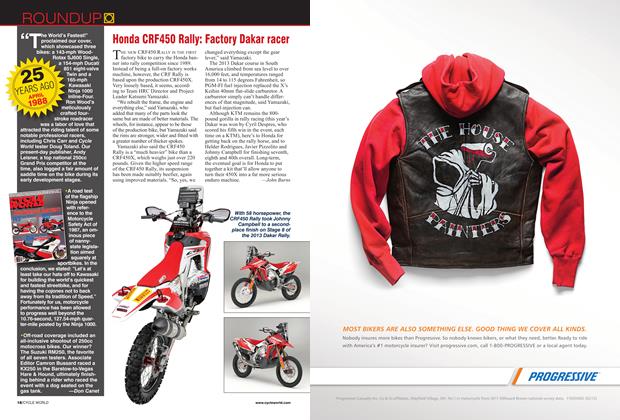

Roundup25 Years Ago April 1988

APRIL 2013 By Don Canet -

Roundup

RoundupWill Elastomers Change Helmet Design?

APRIL 2013 By Andrew Bornhop -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

APRIL 2013