Middleweight Motorcycles

Winning friends and influencing people for more than 100 years

PETER EGAN

IN CONSULTING ONE OF MY ANCIENT Cycle World Buyer's Guides from the last century—yes, these sacred texts have survived five moves and two trips across the U.S. in Mayflower trucks—I can't help but notice that there are almost no bikes depicted that would now be considered "large." Middleweights and lightweights rule the universe, and really big bikes are as rare as monster trucks at a Sierra Club meeting.

The Buyer's Guide I'm looking at is from 1976, and the only two large bikes I can find within its 202 pages are a Harley-Davidson FLH1200, which weighs in at a then-astounding 722 pounds, and a 583-lb. Honda GL 1000 Gold Wing. The Gold Wing is a naked bike, still frozen in that era when few manufacturers made their own fairings. Even the BMWs are all unfaired, except for the 474-lb. R90/S with its small, café-racer handlebar fairing, and it is the company's most massive roadburner. Everything else in the issue is as diminutive as—or much smaller than—what we would now call a middleweight.

What was I riding that year? Well, I had a 1974 Honda 400F and a 1975 Norton 850 Commando, the Interstate version with the big tank. I thought the Norton was a big fire-breather at the time, but when you look at one now, it seems as small and spare as a bicycle. But big motorcycles were anathema then, almost a contradiction in terms. You might as well have tried to sell the public a Pitts biplane "now larger than ever and packed with ground-hugging concrete" or a 30-foot whitewater canoe made of solid bronze. Bulk and density were not wanted by most riders in a sport that was understood to be fun only within a narrow range of physical law. Even the Harley FLH, which existed in a subculture of its own, had a low seat and a low center of gravity (then as now) and was quite manageable by shorter and lighter-weight riders.

People, of course, were a little smaller then, too. Obesity was considered a tragic anomaly rather than a lifestyle choice among the American population, and most of my riding friends and I looked like starved greyhounds by comparison with our present selves. I'm now only 12 lb. heavier than I was in 1976, but some of the weight seems to have shifted a bit; so, when I sit on a Honda 400F today, I feel that either I've doubled in size or the bike has somehow shrunk in the clothesdryer of Time. So—oddly enough—have my old racing leathers...

But bikes have metamorphosed, too, and our big cruisers and touring bikes are a lot more massive than anything imagined in 1976. Also, we have a whole class of large-displacement adventure-touring bikes that—even if not excessively heavy—are very tall. I have a Buell Ulysses that's reasonably compact and agile for its displacement, but it wouldn't break my heart if the seat were 2 or 3 inches lower. This bike is just millimeters below what I consider an attainable pole-vaulting record.

No surprise, then, that this past summer, I've done about 80 percent of my riding on my 1975 Honda CB550 and now the '08 Triumph Bonneville I recently bought, simply because they're easier to throw a leg over and move around the garage. And, once in motion, maybe a little more adaptable to sudden changes of plan— such as turning around in the middle of the highway to go back and take a look at that CB350 (perhaps the most popular light-middleweight in history) for sale in the farmyard. Sometimes, bulk and height on a motorcycle can act as a subliminal barrier that keeps you from riding as often. It's like the old rule in sailboats: For every two added feet of hull length, you'll sail half as often.

There is, of course, much to be said for a certain amount of structural heft on a large, two-up touring bike with luggage—especially if it includes a big plush seat, a windshield and an engine capable of pushing all this tonnage down the road. But when I look back on a lifetime of touring, my two favorite road trips were taken on a Honda 400F and a 2003 Triumph Bonneville, mostly because of their effortless maneuverability—and a factor you might call "explorability." 1 should admit, however, that both these trips took me through the Blues country of the Mississippi Delta, so I may be unfairly biased in their favor. Still, when you absolutely need to find the grave of Mississippi John Hurt on a rutted dirt road in the deep woods near the village of Avalon, a moderately light streetbike is your friend. No such mystical shrines are found on the Interstate.

In the box-stock roadracing I did back in the late Seventies and early Eighties, middleweights were also my preferred choice. My favorite was a 1981 Kawasaki KZ750, followed by a silver 1980 Honda 750F Super Sport whose slower steering made it occasionally run a little wide in sweepers. Which, in turn, made my eyeballs run a little wide as the Armco approached. In any case, both these bikes were big enough to have a nice kick coming off corners but not so large you felt the bike was taking you for a ride. Magazine writers at the time rhapsodized eloquently on 750s as being exactly the right displacement for a motorcycle, balanced on a perfect fulcrum point between weight and performance. This truism was widely repeated by those of us who owned or raced them. I think they were right then and probably still are.

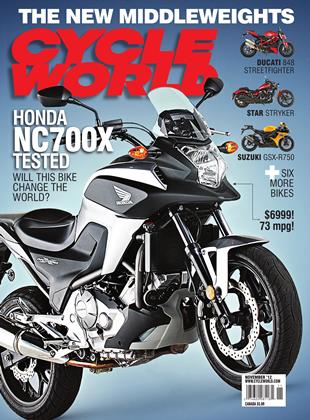

So, what is the right size for a "middleweight" motorcycle? Well, we've got a bunch of them in this issue that pretty much satisfy my definition, and, happily, displacement and bulk are no longer automatically connected. You can have a 1200 Sportster that's no bigger than the 883 version—or than my old Honda 550, for that matter—yet much more powerful. These are good times for middleweights and their engines.

But if someone asks me for a classic definition of "middleweight," the image that instantly pops into my head is that of a 1970 Triumph Bonneville, whose red and silver paint scheme (don't you know) is nearly identical to that on my 2008 Bonneville. When I sit on one of these bikes, look down at that slim tank and then rock it from side to side on its tires, it just automatically makes me say, "Yes!" Everything larger seems to have something superfluous about it, and everything smaller seems a little less roomy and rangy, less fully adult in scale.

But then, the majority of all popular motorcycles built over the last century have not been too far away from that Triumph Bonneville in either size or weight. That's because basic human architecture doesn't change radically (high fructose corn syrup notwithstanding), gravity remains reasonably constant and dropping a big, fat bike on your leg remains embarrassing. Also, most of us ride for fun and a sense of freedom. And sometimes, a little moderation—in this rare exception to the rule—can set you free. O

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

NOVEMBER 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupNo Quarter Given

NOVEMBER 2012 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago November 1987

NOVEMBER 2012 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupWill the Motorcycle of the Future Come From Pasadena?

NOVEMBER 2012 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

Roundup2013 Harley-Davidsons

NOVEMBER 2012 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

RoundupOn the Record:

NOVEMBER 2012 By Matthew Miles