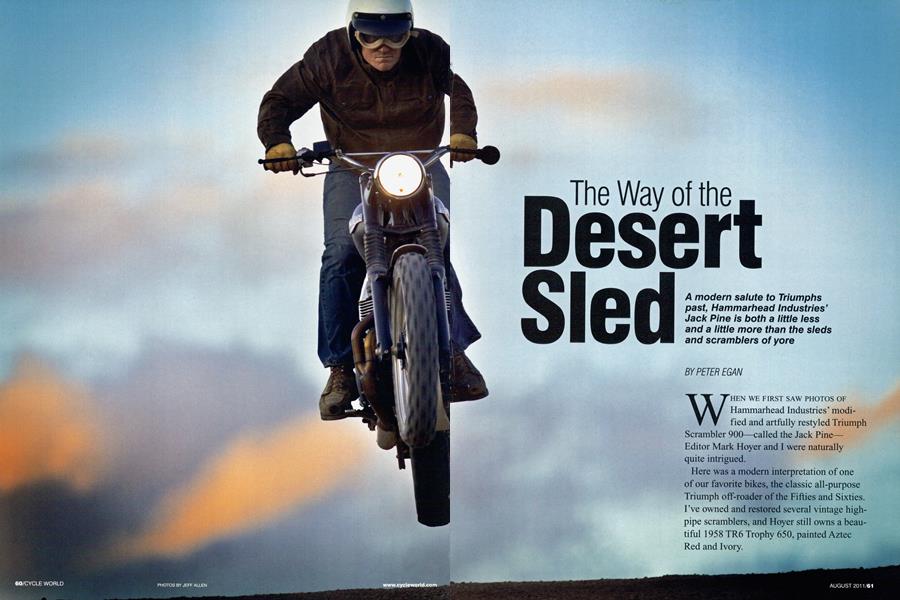

The Way of the Desert Sled

A modern salute to Triumphs past, Hammarhead Industries' Jack Pine is both a little less and a little more than the sleds and scramblers of yore

PETER EGAN

WHEN WE FIRST SAW PHOTOS OF Hammarhead Industries’ modified and artfully restyled Triumph Scrambler 900—called the Jack Pine— Editor Mark Hoyer and I were naturally quite intrigued.

Here was a modern interpretation of one of our favorite bikes, the classic all-purpose Triumph off-roader of the Fifties and Sixties. I’ve owned and restored several vintage highpipe scramblers, and Hoyer still owns a beautiful 1958 TR6 Trophy 650, painted Aztec Red and Ivory.

Why don't you come out to California," he suggested~, "ad we'll take the new Jack Pine up into the desert near Lone Pine, north of Death Valley. I'll bring my bike, and our bud dy Bill Getty, has volunteered to bnng Roger White's 1958 Big Bearwinner along for photos. We can do a kind of old/new desert-sled comparison."

Sounded good to me, as I'd never ac ually ridden a Triumph-old or newn the desert. By the time I got hired by Cycle World and moved to California onda XRs. Ti picture,

the Midwest, where I grew up Maybe it was the climate Our world tended to filled with green pastures, narrow traiL through the woods and boggy water crossings rather than yucca trees and~ unimaginably empty miles of hard gravel stretching off into infinity The IosestfbitLg we had t&a desert was parking kt at bwidreds of motorcycles btazm~ away~ We~ certaini

pick up a motorcycI~~u~à~thout! seeing an pic widescreen phot~w1th1 hese desert bikes Yotz in the distant t1flt~1n*~)t~ bUm,ng~ pile of tires in the nuddle of nowher(i~ An4~ as you might guess, the classic desert sled was not commonly found in

Surfing.. .California is. What was I doing Sliding my Honda Super 90 [ abandoned baseball diamond, that’s what. Some desert. ¡ mm I believe the first time I actually hear« the term “desert sled” was in March of 1974, when Cycle magazine published a story by the great Gordon Jennings called “The Glory Days of the Desert Sleds.”

Jennings explained that there had been a magical time after World War II when the deserts of America’s «•»./*. ' • ton on every-_? one’s list of places to avoid.” Almost everyone in those days saw the desert not as a part of Nature but rather as the near-absence of it. A perfect place for atomic tests and gunnery ranges. And dirtbikes.

The early desert racers of the late Forties tended to favor British Singles, but when Triumph finally introduced its own swingarm rear suspension in 1954, „ many riders—including the legendary Bud Ekins—switched to the relatively light and powerful Triumph Twins. By 1958, when Roger White won the Big Bar Run on the very Triumph shown 'Q (beating 821 other riders across 153 miles of open desert and mountain trails), Triumph riders accounted for eight of the top 10 places and 57 of the 134 finishers.

What did competitors do to prepare these virtual streetbikes for the rigors of this madness? According to Jennings, most riders simply removed the lights, then added a cushier seat (often Bates), high-mounted straight pipes, skidplate, wider bars, better air filters, higher fenders and knobby tires—usually a Dunlop Trials Universal on the front and a Dunlop Sports for the rear. Some stretched out the steering-head angle for more high-speed stability. Not much engine modification was done; they already had enough power for the job. Troublefree single-carb heads were preferred.

By the late Sixties, lighter and morenimble two-strokes, such as the Husky 250s, started to take over. Courses became shorter and more technical, relegating the Triumphs to vintage (i.e. dinosaur) status, and the day of the Sled was over. Still, these bikes looked better—and had more charisma and history—than anything else that ever plied the desert sands. Or so some of us believe.

And so thought a 45-year-old gentleman named James Loughead (pronounced lawhead) of Philadelphia, who builds the Hammarhead Jack Pine.

A little explanation of the brand name here: Loughead married a woman named Hammarlund, and they cleverly combined their names. He teaches neuropsychology at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School when not redesigning Triumphs—or Urals and Enfields—and riding his dirtbikes, scooters or Honda Transalp. Or touring India on an Enfield Bullet.

Too much energy, in other words. He told us his specialty is schizophrenia and addictions, which caused Hoyer, Getty and me to quickly steer him away from our dark personal histories of serial Triumph ownership.

When the new Triumph 900 Scrambler came out a few years ago, Dr. Loughead saw an opportunity for improvement in aesthetics and performance. He said he didn’t want to build a retro bike so much as a “simple bike,’

a clean and thoroughly modern expression of the traditional Triumph virtues. Not a bike to pick up where Ekins or off-road legend Bill Baird left off, by winning modern desert races or the Jack Pine Enduro back East, but a bike you could ride to work “or Alaska.”

At present, he has four Jack Pines completed, three in the hands of owners, with three more on order for 2011. The price of a complete bike is $14,500—or $5000 less if you provide your own Scrambler donor bike.

So, what’s his recipe?

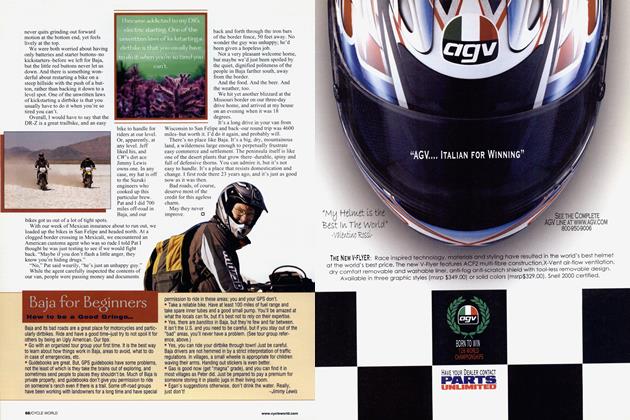

First, he starts with a standard, carbureted 2007-08 Scrambler and strips the entire bike. He cuts off the passengerpeg triangles and 4 inches of frame at the rear-fender extension, then shortens and reupholsters the stock seat pan. He also cuts off the stock oil-cooler mounts and installs a more-compact single-pass oil cooler with hard lines between the front downtubes. No-name, modified Taiwanese aluminum fenders are added, front and rear, with a small LED taillight and tiny tumsignals sunk into the rear frame uprights and headlight-mount ears.

Engine internals are stock, but Loughead machines a set of shortened intake runners so he can fit a pair of 35mm Keihin CR round-slide carburetors with K&N pancake air filters. This eliminates the airbox and allows all electrics and the horn to be concentrated (and hidden) under the sidecovers. The countershaft sprocket is dropped one tooth, to 17, and uses an alloy cover made, like the pegs and small bar-end mirror, by Joker Machine.

Stock 19-in. front and 17-in. rear wheels are also used, but the tires are adventure-touring-style Continental Twinduros. The fork springs and shocks are from Works Performance, with heavier oil in the fork.

The de-clutterated aftermarket handlebars use Brembo master and levers, older Honda switchgear and a lovely little custom-machined, alloy multi-function turnsignal switch. The only instrument is a digital speedometer mounted in the top of the headlight.

While some customers have asked for high-mounted pipes, Loughead prefers the simplicity, narrowness and light weight of the Zard 2-into-l low pipe and small muffler, and our bike was so-equipped.

Paint? Semi-flat black. No options here; Loughead thinks it looks just right. And it does. A clean and purposeful bike to look upon. But how does she ride?

To find out, we met Loughead (who rode our testbike down from San Francisco) in Lone Pine and headed out onto the trails of the famous Alabama Hills, right in the shadow of snowcapped Mt. Whitney. This is a boulderstrewn landscape where virtually every Western matinee movie was shot when I was a kid—Lone Ranger, Hopalong Cassidy, Roy Rogers, etc. Getty showed up with two genuine vintage desert sleds in the back of his classic 1971 El Camino—the Roger White bike and his own high-patina 1954 Tiger Tl 10, on which he has finished eight of nine attempted Barstow-to-Vegas dual-sport rides. Mag trouble, that one year.

Trail conditions were rather dry and slidey. I took a short ride and likened it to “bird shot on a polished dance floor”—but we luckily had our own Mark Cernicky along, a guy who can ride anything anywhere, as long as it’s mostly sideways with the throttle on. Sane people watch and take one step backward.

Cernicky was initially a little unnerved by the 450-pound dry weight of the bike (44 lb. lighter than stock, but still no KTM) and the lack of traction and front-end bite with the not-quiteknobby Twinduros on the hard-baked sandy surface. But he soon adapted and was roaring sideways between the boulders with both ends throwing sand at our cameras. The exhaust note from the Zard system was just right: hard-hitting traditional Triumph (even with that 270-degree crank) but not excessively loud. Well, it’s not too loud for the wide-open spaces of the desert!

I rode the bike briefly in the dirt, then took a long, winding highway ride to our next photo stop at the Pinnacles—an unearthly landscape of weird, giant stalagmites nearTrona. Much fun. The big CR carbs are perfectly dialed-in, the suspension is a little firmer than stock but well-controlled, and the sound from that exhaust system is marvelous. Bars, seat and pegs, just right. Nice turn-in and grip with the Continentals on the pavement. You can’t really read that little speedometer in sunlight, and cars behind you may not be able to see the tiny twinkle of those downsized tumsignals in daylight, but the bar-end mirror was surprisingly adequate to keep me from being ambushed from the rear.

I did 5 miles of rutted dirt road on the way into the Pinnacles and found the Jack Pine quite manageable on this slightly coarser and loamier surface, but I still wished for real knobbies in the dirt. It didn’t have the suspension travel or grace over potholes of my old KTM 950 Adventure, but the low ride height and compactness of the Triumph made it feel user-friendly and fun. Yes, I’d ride one to Alaska...

Editor Hoyer also kindly let me ride his 1958 bike for a short run through the dirt and out on the highway, and it felt even smaller and lighter. The right-side shifter had a lovely counterweighted slickness to it but was not as precise and positive as the new bike’s left-side lever. Cernicky, still experimenting with this antediluvian shift pattern, said he kept finding false neutrals, and the bars were too narrow for him. Otherwise, a sweet bike, with nice natural steering and good (if not as much) torque and power. And yes, there was some oil misting and clinging of dust at the mated engine surfaces.

The main difference to me was that the Jack Pine felt tight and solid, as though you could flog it all day without having anything break. Meanwhile, Hoyer’s old TR6 felt more charming than bulletproof, but that may just be from the respect we carry for old things in our own brains.

People rode the hell out of these bikes in their day, but now we don’t really want to. They’ve done their work, carrying guys like Ekins and White and Mulder across brutal miles of wilderness and desert, streaking toward some invisible point in the distance, back when we still had blank spots on the map. The real off-road racing days of the Sled are over, but the versatility of this kind of bike—and the appeal of that look and sound—probably never will be.

"The big CR carbs are perfectly dialed-in, the suspension is a little firmer than stock but well-controlled, and the sound from that exhaust system is marvelous."

Scan for more photos and video

cycleworld.com/sleds

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

AUGUST 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupSometimes You Win

AUGUST 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupGet Healthy, Ride A Motorcycle

AUGUST 2011 By Philippe Devos -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago August 1986

AUGUST 2011 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupBrammo Shifts Gears

AUGUST 2011 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupOff the Reservation

AUGUST 2011 By Marc Cook