FREE RADICAL

Sensory overload at Radical Ducati, where lightness is a fundamental element of cool

GARY INMAN

EVERY DETAIL IN THE RADICAL DUCATI UNIVERSE SETS MY SPIDER senses tingling. From the minute I walk through the door of their concrete unit on the outskirts of Madrid, Spain, everything is right with the world.

SIGHT

My eyes flit like a butterfly, and each place they land is sweeter and more interesting than the last. Light streams through a large window at the far end of the premises, giving the headquarters a dream-like atmosphere. I ion’t know what I was expecting, but it wasn’t this. Every surface is covered in eye candy.

Eventually, Pepo Rousel, Mr. Radical Ducati, says, “I wanted it to be like my customers’ dream garage.”

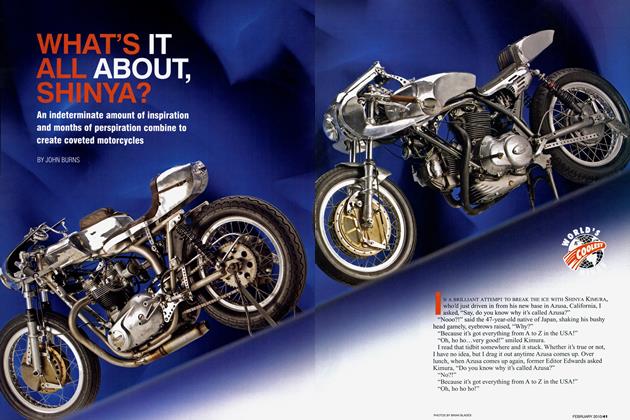

Radical’s project bikes line either side of the first half of the 100-foot-long industrial unit. The majority are minimal, like bikes used to be, but modern. They tend to be stripped-to-the-bone and harder than a riot cop’s baton.

Contrasting to the tough bikes is Radical’s logo featuring the cheeky cartoon cat Felix. There are none of the tedious macho skulls or ace of spades that custom builders seem to use as a default. Radical consistently cuts its own path. Of course, they have outside influences, but Rousel has such strong and unbending opinions that Radical always stands out.

Rousel has loved and worked with Ducatis for most of his adult life, and while he happily modifies 749s, injected Multistradas and 1098s, his ethics and much of the company’s aesthetic is based in the past and two-valve motors. But don’t think they’re some kind of backwardlooking restoration firm.

“We make bikes the way Ducati made them in the Seventies: with a race mentality,” Rousel explains. “Now, even simple maintenance on the new bikes is very difficult. Did you know you have to remove over 20 screws to get to the battery of the new Monster? It’s crazy!

“The motorcycle industry has arrived at a point of stupidity. Bikes are now so sophisticated they may as well be cars. Soon, when a headlight bulb blows, the bike’s safety system will stop the engine. The Multistrada 1200 is very nice, but if the electronics say ‘Goodbye,’ you’re [screwed]. The company doesn’t listen to what the Ducatisti want. They’re building fashion bikes. Ducati is a prisoner of its image. When Cagiva left, when the Castiglionis [who now own MV Agusta] sold the company, everything changed. Ducati was always avant garde, but the 1098 is a copy of the 916.”

Scan for more photos

cycleworld.com/radical

Rousel is talking about his favorite subject, and it’s hard to stop him. He has loved Ducati for so long. He worked for the Spanish importers and visited Bologna before the four-valve 851 made it into production, back when very few cared about Ducati (despite what the company’s rewriting of history wants you to believe).

HEAR

Rousel pushes Radical’s latest bike, Pursang, out of the shop and into the cold, semi-enclosed concrete tunnel that leads to his headquarters. Then he starts it and I almost jump for cover as if a bomb had gone off. I like motorcycles to sound like motorcycles, but this thing is obscene. By the end of the day, I’ll discover all Radical Ducatis are characterized by pain-threshold noise levels. Hey, Pepo, have you never heard of baffling? I said, HAVE YOU NEVER HEARD OF BAFFLING?!

Pursang—meaning pure blood or thoroughbred—was built from the wrecked remains of a Multistrada 1100, but there isn’t much left of the original bike. Amazingly, it is inspired, says Rousel, by my hobby magazine, Sideburn, and the stripped-down dirt-track racebikes and street-trackers it features.

“I see there are two powerful movements in the motorcycle world at the moment, café racers and street trackers,” he says. “They have two things in common: They’re simple and they’re fun.”

The frame may look like a standard Ducati trellis but is, in fact, high-grade chrome-moly and 7 pounds lighter than standard. The fuel tank is Radical’s own. It was designed by Michael Uhlarik, a former Yamaha designer. For a time, Rousel was a fan of what Yamaha was creating. He liked the YZF-R6, MTOS concept bike and the MT-03. He discovered Uhlarik had a hand in all of them, so he commissioned him to create RAD-01. The result was a full body kit that transformed the 999/749. It had Plexiglass sidelights, inspired by late-Sixties race cars. Rousel loved the deisgn but always liked the tank best.

Pursang’s seat is also an original design commissioned by Radical, this time drawn by young Spaniard Carlos Beltran.

SMELL

Pursang is so new it still needs to be set up properly, and the exhaust smells like the bike is running rich. It can be excused. Rousel discarded the Multistrada’s fuel-injection system in favor of 41mm Keihin flat-slide carbs. “I was bored working with fuel injection,” he explains. “With fuel injection, you just type in a map. It’s too easy.”

This is the first bike Radical has built with high bars rather than clip-ons. “I wanted to show what a streetfighter must be,” he says, having another dig at Ducati. “More pure, more simple.”

Very few of the suppliers Radical uses are well-known names, but he prefers to deal with the companies he describes as “artisans.”

“People think you’re an idiot if you don’t use STM clutches and Termignoni exhausts,” says Rousel. He doesn’t use either. He sells clutches made by EVR and says they’re better than STM, while silencers are from Spark. “They make exhausts for Lamborghini, AMG, Guzzi, Aprilia and prototypes for Termignoni,” he claims.

And instead of Brembo, Radical prefers Discacciati, run by Enrico Discacciati. “He used to be the head of Brembo,” says Rousel.

Much of the rest of Pursang, like all Radical bikes, is a mixture of desirable parts from Ducati production bikes. The swingarm is from a Monster S4R and heavier than Rousel would like it to be, but “customers like them.” The suspension is from Ducati’s S-model superbikes (998S, 999S, etc).

TOUCH

Even before I ride the Pursang, just pushing it around, it’s clear Radical builds very light bikes.

“Ducati must build bikes with 40-60 pounds less weight,” he says in another declaration. “We do. It’s easy. Ducatis should be ‘no compromise.’ They’re making bikes for yuppies. And girls!”

He hasn’t finished yet. He starts on the SportClassics: “They should make real Ducatis. They’re arrogant. The SportClassic? It’s a piece of plastic with twin shocks. It’s not a bike, it’s a cow!”

I realize I’m standing with my mouth half-open. I love hearing opinions, whether I agree or not, especially where they’re delivered with such passion and from a man who can back it all up with his actions.

The black racebike (bottom right) is the RAD Uno, so named because the power-to-weight ratio is virtually 1:1. “It weighs 134 kilos [306 pounds] with battery, oil, water and some fuel, and it makes 134 bhp. Real bhp, not Dynojet bhp,” says Rousel. That’s another annoyance for him, the optimism he believes certain dynos have. He reckons the one he uses is more true...

The Uno has a Radical RAD-02 frame, but in aluminum, not chrome moly. Rousel sells this frame for race use only, not road. It's powered by a 999 engine. "We prefer the two-valve motors. They're more romantic, but when people touch our bollocks," he says, using an Englishism in a translated Spanish phrase, "we have to build some thing to prove we can. We used a 2003 999 engine, the oldest, so the satisfac tion of going to the track and beating a 1098 that has 30 bhp more is great. Of course, we have 110 pounds less..."

TASTE

Pepo and his wife, Ramon Reyes, started Radical Ducati in Valencia in 2001. They soon moved back to Madrid, where they both grew up, into a small, inner-city shop. Two years ago, they relocated to this unit. Radical has huge ambitions, but not ambitions to be huge. Its bikes are like nothing else in the world.

The 914 (bottom left) is what the British call a “bitsa.” It’s made with bitsa this and bitsa that, but such is Rousel’s eye and good taste, he makes it work so much better than it should. I had taster rides on a couple of the bikes, just short blasts, because neither were road-registered. It made my desire for a bike built the Radical way even more desperate. I’d have high bars like the Pursang and retro paint like the 914, and a quieter exhaust, please.

“It is very difficult to run a business like Radical,” Rousel explains at the end of my two days with him. “The whole business is in my head: the budgets, the new projects, the paperwork... And I have to think, ‘What will we do tomorrow that’s new to astonish people so they call again?”’

Rousel doesn’t answer his own question, but I know he has something in mind. Businesses as specialized as this don’t survive for 10 years unless they have a plan.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

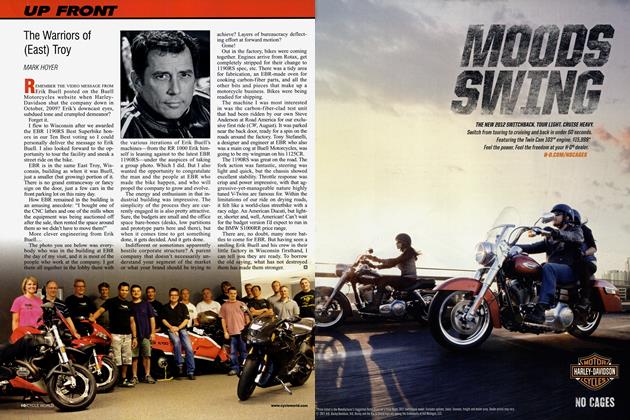

ColumnsUp Front

November 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

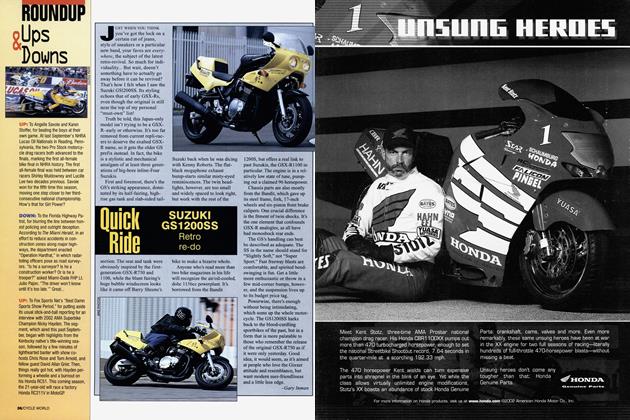

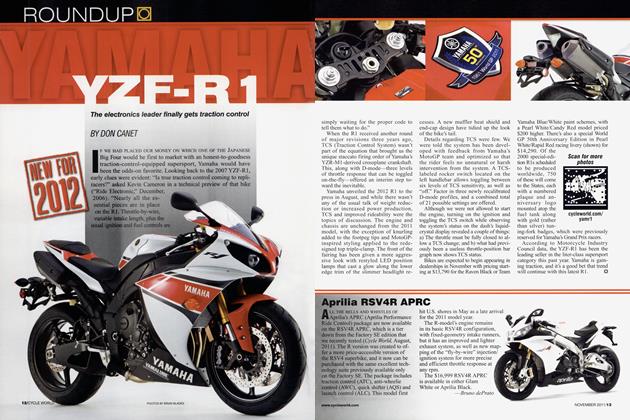

Roundup

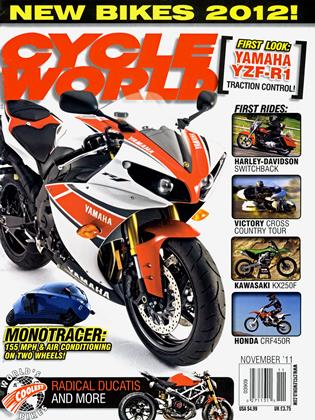

RoundupYamaha Yzf-R1

November 2011 By Don Canet -

Roundup

RoundupThe Future of Mx?

November 2011 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupMission Accomplished: Rapp Wins At Laguna

November 2011 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupFonzie's Triumph To Auction

November 2011 By Robert Stokstad -

25 Years Ago November 1986

November 2011 By Don Canet