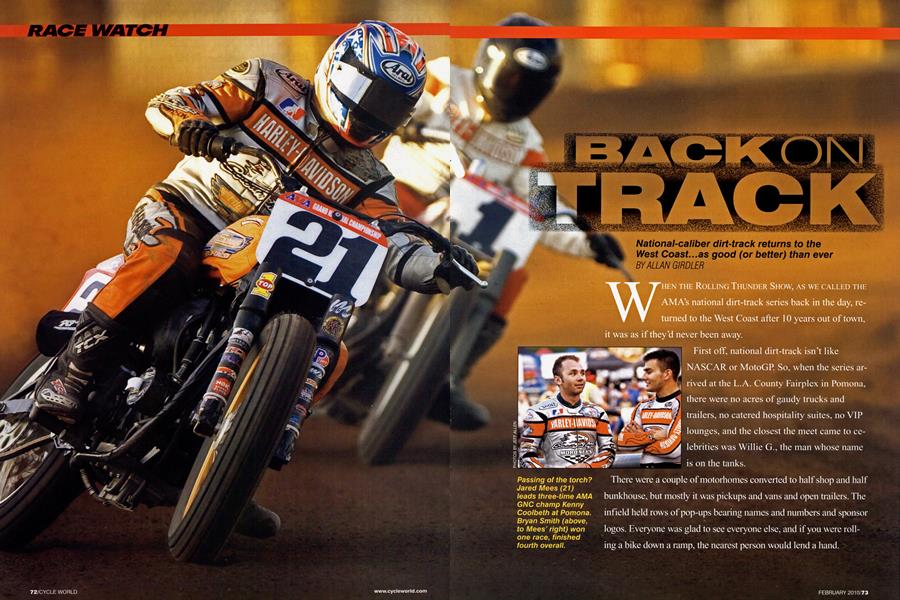

RACE WATCH

BACK ON TRACK

National-caliber dirt-track returns to the West Coast...as good (or better) than ever

ALLAN GIRDLER

WHEN THE ROLLING THUNDER SHOW, AS WE CALLED THE AMA's national dirt-track series back in the day, returned to the West Coast after 10 years out of town, it was as if they'd never been away.

First off, national dirt-track isn’t like NASCAR or MotoGR So, when the series arrived at the L.A. County Fairplex in Pomona, there were no acres of gaudy trucks and trailers, no catered hospitality suites, no VIP lounges, and the closest the meet came to celebrities was Willie G., the man whose name is on the tanks.

There were a couple of motorhomes converted to half shop and half bunkhouse, but mostly it was pickups and vans and open trailers. The infield held rows of pop-ups bearing names and numbers and sponsor logos. Everyone was glad to see everyone else, and if you were rolling a bike down a ramp, the nearest person would lend a hand.

The names were different, seventime number-one Chris Carr being one exception. (In case you missed it, Carr is once again the world’s fastest rider, at 367 mph and change.) Even so, the riders are still young, compact and fit, mostly guys but a couple of gals who’ve earned their licenses. They come from small towns and close families, so there are moms and dads and so forth, tuning the bikes and setting out the T-shirts and posters.

There was a difference, and it’s a plus. But first, as briefly as possible, some background.

Grand National racing disappeared from the West Coast by accident, an unhappy combination of pavement, politics and personal disagreements. World-famous Ascot and the legendary San Jose and Sacramento Miles were replaced with club meets and local tracks, with the occasional exceptions of the Lodi Motorcycle Club and the Southern California Flat Track Association.

The vital exception was Gene Romero.

Bruce Brown’s movies don’t have villains; it’s good guys meeting challenges. But even so, On Any Sunday starred Mert Lawwill in defense of his number-one plate, so because Lawwill lost the plate and Romero won it, Romero comes as close to a Bruce Brown villain as one can get.

And then, when Honda decided to win that plate, the only major title they hadn’t won, they tried an in-house team and were hopelessly defeated. They hired Romero and some other locals and won so handily that the AMA had to juggle the rules to keep the other brands— okay, make that H-D—in contention.

Honda promptly quit as winners, doing the brand, team and owners of the ex-team bikes no good at all, so Romero began promoting races, in the form of the West Coast Flat Track Series, with events in Oregon, California and Nevada, never mind how often the surf's up in Las Vegas.

He did most things right. The Pro classes for Twins and Singles pretty much match the AMA rules, so rac ers can run in both series with the same machines, and the vintage class contains anything that will run, as in Harley, Yamaha, Triumph and BSA in years and equipment that won't meet, say, the usual vintage limits.

But best, Romero's series has been promoted as entertainment, for the fans as much as for the riders and spon sors. And Romero has worked with the fair-board guys, the track owners, the sanctioning bodies and clubs, while the other promoters have been poster boys for Tom Petty's "I Won't Back Down."

Therefore, when the AMA sold its fading dirt-track venue to the Daytona Motorsports Group and they hired Mike Kidd, the GNC champ in 1981, to run the series, Kidd and Romero got together and organized Romero's Pomona date as a combined meetGNc, plus WCFTS.

What this meant was, alongside the kids and families, we had coots and fami lies, also from all across the country, re tired Pros and hobby tuners who'd man aged to buy an XR-750 or in one case, and I'm not making this up, a replica of the infamous Champion-framed Yamaha TZ750-powered bike that Kenny Roberts rode in 1975. (The owner didn't actually run it, not on a rough, 5/8-mile track with long straights and tight turns-score one for cooler heads.)

The actual event began before the events seen here. The original plan was a SoCal Bike Week, Pomona races fol lowed by the Love Ride-except that the ride sponsors cancelled on grounds the economy wouldn't justify the expenses. But meanwhile, Romero and Vince Graves, who promotes the club races at Perris Raceway about 60 miles east of L.A., did a deal. Perris had a race scheduled for Saturday night, same as Pomona, which would hurt all parties. They agreed to move Perris to Friday night, so the racers in town for the big meet could warm up and maybe earn some money because the Perris event was a memorial for old-time club member Mike Perez, with the biggest purse of the year.

And so?

So when sign-up closed Friday night, Perris had 25 Pros entered, some local but most there to practice for the big meet. One of those was Joe Kopp, 2000 GNC titlist and one of the few who has won all four—short-track, TT, halfmile and mile—national venues. No surprise, Kopp won the main and the dash for cash, closely trailed in both races by the club’s best, National #37 Jimmy Wood, proving that the locals are pretty good. And speaking of family, Kopp had as much fun coaching son Kody to victory in the 50cc class.

Back in the big-time, Saturday parking at Pomona was just like always—rows of big cars and Big Twins. Say what you will about stereotypes, fact is, the street Harley guys are hardcore race fans. What mattered more, the grandstand is big, and it was full, not packed, but full. The crowd turned out justifying Romero’s investment and that of Saddlemen and K&N, who each sponsor one of Romero’s classes.

Because there were 31 races on the program, counting heats and semis, etc., we’ll begin at the top: The GNC Twins class has been contentious at least since the series as such began in 1954, with the debate generally based on, How Come Harley Always Wins?

This is because first, excepting the Honda campaign mentioned earlier, The Motor Company’s XR-750 has been the dominant model since the alloy version was introduced in 1972. The AMA and now DMG have been pushing and pulling the envelope, searching for a way to attract the major makers while not devaluing the scores of XRs that do, in fact, make up most of the grid. The series is open to publicly sold engines in frames of choice, with various limits here and there. So when qualifying ended, we had some variety.

There was Bill Werner, GNC’s winningest tuner, with his eBay-sourced Kawasaki 650 Twins; Ron Wood’s raceframed BMW F800, as seen on these pages (“American Beemer,” December, 2007), with Jimmy Wood (no relation to Ron, as it happens) in the saddle. And there were Suzuki 1000s, a Triumph, an Aprilia, one Ducati and one KTM. None of these is fully funded by their factories; all have some help from someplace else.

Fast qualifier was Kopp, 30.32 seconds for the Vs mile, no traction and damp, by the way, with nine other riders less than one second slower, while the slowest—no names; why be rude?—turned 34.09 seconds. And when the 18 qualifiers lined up, there was one Suzuki and 17 Harley XRs. The Wood BMW had a mechanical problem, and the Werner Kawasaki didn’t make the cut.

At the finish, it was Henry Wiles, who earlier this season won the GNC Singles title but had never won a Twins race.

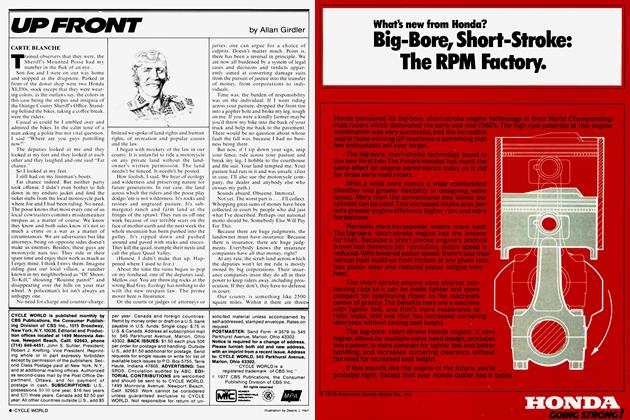

He was followed by three-time champ Kenny Coolbeth, Sammy Halbert, Joe Kopp and Jared Mees, whose high finish gave him the GNC Twins number-one plate, first time in series history anyone has won the series but not won a race.

In Pro Singles—which is the support 450cc class, not the national 450cc class— there were two Yamahas, two Suzukis and 14 Hondas. But no one complained about that because the winner—and top qualifier and leader of the most laps—was Jeff Carver, from Alton, Illinois, on a Yamaha. That series winner, Brad Baker of Chehalis, Washington, was second, on a Honda. Interestingly, the 450s— motocross frames with modified suspension and semi-knobbed tires—were lapping in the :32s, not all that much slower than the Twins.

WCFTS vintage rules are so open that surely for the first time in racing history, the field contained Harley XRs and a 60-year-old Indian Scout—yes, the flathead 750. The winner? Ricky Henson on—what else?—an XR, followed by none other than John Hateley, former national #98 and two-time winner, in 1972 and ’77, of the Houston TT, trailed by former speedway star Ricky Hocking, Triumphand Harleymounted, respectively. Perhaps to show he can ride big bikes, Wiles won the WCFTS Open class on the same Harley, with the same throttle control displayed in the GNC race.

Where was Kopp? Re-started, after another rider fell, in last place due to a stuck rear brake. He worked his way back to fourth, having made the restart because in GNC, a rider who needs a 7/i 6-inch wrench leans over the railing and asks the nearest person, who then sprints to the closest pit and borrows the wrench—no questions asked, happy to help.

Try that in MotoGP.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSeizing the Means of Production

FEBRUARY 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupSexysix

FEBRUARY 2010 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupKiller Concepts

FEBRUARY 2010 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

Roundup2010 Mv Agusta F4

FEBRUARY 2010 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupKtm Concept 125 Supermoto Racers

FEBRUARY 2010 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupBetter Boxers

FEBRUARY 2010 By Bruno Deprato